Mining the Past to Understand the Present

By Margaret Ann Spence

The mid-century, before the baby-boomers became teenagers and horrified their parents, was, it is said, a time of stifling conformity. Strange. That is not how I remember this time at all. So, I wrote a memoir to set the record straight. In writing Cold War in a Hot Kitchen: a memoir of mid-century Melbourne I discovered two things: The 1950s, in Melbourne, Australia, were decidedly not boring, and that women paid a price for political choices made by men.

Belying its popular image, this period was a time of tremendous upheaval and tension, of the world recovering from the trauma of World War II, facing the possibility of a third world war, with the atom bomb a threat over the world’s very existence. My family was embedded in these tensions as the Cold War deepened in this part of the world. In fact, the “domino” theory of communist advance was very relevant to Australia given its proximity to Asia. In my early childhood, the countries of Southeast Asia were beset by civil war, and Mao Tse Tung led a communist victory in China. Domestic politics were in ferment. Whether socialism and communism were to be feared or welcomed was not at all clear, even in our own home. As it happened, the Cold War outside echoed a cold war chilling our household.

We did not live in a typical household of mother, father, and children. Or rather, my parents lived this ideal for a very short time, before we lost the lease on our house and had to go and live with relatives when I was three; before my mother’s sister fled her husband with her baby daughter and came to live with us when I was almost four; before my paternal grandmother Eva bought a house big enough for all of us and commanded that we come and live with her, when I was just five.

Eva, from a genteel English family, had brought up four children in remote Western Australian mining townships before her husband’s job took him to manage one of the country’s biggest goldmines, allowing her to live like a duchess in her tiny society. Now, in the cooler Eastern city of Melbourne, no one understood the life she’d lived, her privations and her triumphs. It was if she had come from Mars. But she was British, and better, she said, than any of us.

Battle lines were drawn between my mother and her mother-in-law from the day we moved into the home my grandmother had bought. In the 1950s women’s place was in the home. But some women did not want to stay there, including my aunt. Soon, tensions erupted between my mother and her free-spirited sister, who was at the time a newspaper reporter. I adored this aunt, and wanted to emulate her, but she transgressed social norms, causing great anxiety. She eventually became a well-known feminist journalist. At the same time, an influx of refugees from war-torn Europe, and my parents’ friendships with them, offered glimpses of other ways of life, glimpses of opportunity, at the price of upheaval.

My head spun like a top at these different versions of how to grow up. Sweet but self-denying like my mother, a glamorous writer who bucked convention like my aunt, or adventurous and determined like my grandmother, a woman I came to secretly admire for her pluck. Our Granny had acted more like a man in seeking her own fortune and finding it across the world. But no one liked her. She was unsentimental; the hardships she’d endured had made her emotionally inaccessible. Yet she dominated our household. That confused me. Should a woman stay close to home, or should she be able to choose her own path without condemnation? It is a question still relevant for girls.

I began to research the history of the mid-century and found a trove. I was fortunate because my family writes. Letters, journals, newspaper articles written by my aunt and others, books written by my political scientist godfather, as well as a cache of articles about family members now available through a digital source called, appropriately enough, Trove, were my main sources, leading me to books and articles by historians and sociologists of the time.

When I started Cold War in a Hot Kitchen, I only wanted to share the experiences of my Australian childhood with my American children. As I wrote, though, I realized that here was a tale worth telling, both personal and universal, in my family’s interaction with the world around them. My mother, her sister, and my paternal grandmother, all different, but all in their own ways struggling against patriarchal values and control, became the crux of the story.

Cold War in a Hot Kitchen took years to write, between life events. I had no idea when I started that many of its themes would become topical again today. The world is again afire with war, refugees seek shelter from famine and conflict, and women’s hard-won rights are under threat.

A quarter of the way into the next century, the issues of the 1950s are still relevant, some still unresolved.

—

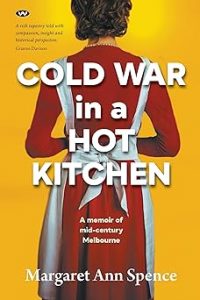

Cold War in the Hot Kitchen: A memoir of mid-century Melbourne

By Margaret Ann Spence

Wakefield Press, Australia, September 2024

The 1950s. Boring? Hardly.

An influx of European refugees, stirrings of feminism, and the threat of a third world war were remaking Australia. As the Cold War chilled, inside a Melbourne house a young girl was caught in the crossfire of domestic conflict amid the clashing political and social values of her autocratic grandmother, her self-denying mother, and her glamorous aunt: three women who presented very different models of womanhood.

—

Margaret Ann Spence, born in Melbourne, Australia, has lived in the United States most of her adult life. She’s worked in publishing, journalism, and public relations, and is the author of two novels, the award-winning Lipstick on the Strawberry, and the award-finalist Joyous Lies.

Author photo by Tolga Toncay

COLD WAR IN A HOT KITCHEN

The 1950s. Boring?

The 1950s. Boring?

Hardly.

An influx of European refugees, stirrings of feminism, and the threat of a third world war were remaking Australia. As the Cold War chilled, inside a Melbourne house a young girl was caught in the crossfire of domestic conflict amid the clashing political and social values of her autocratic grandmother, her self-denying mother, and her glamorous aunt; three women who presented very different models of womanhood.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing