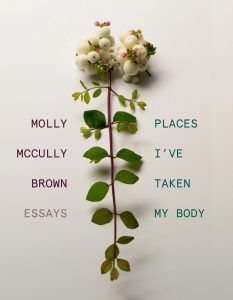

MUSCLE MEMORY: Excerpt

Places I’ve Taken My Body by Molly McCully Brown s a collection of essays about the author’s personal struggles with cerebral palsy, and her evolving understanding of the intersection between her physical body and that intangible other that she has come to call the soul.

Molly is known for her award-winning poetry collection, The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, which was named a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2017.

The State Colony near her home in Virginia (which was an actual institution) haunted Molly. As a person born with a disability, Molly could not help but imagine that she might have suffered the same fate as the patients there, had she been born in that era. The book caught the public’s attention and catapulted Molly into the literary limelight. She was invited to give numerous talks and readings across the country and was featured on NPR and other national media.

Written in introspective and lyrical prose, Places I’ve Taken My Body intertwines in time creating a montage of Molly’s life from childhood until the present. The book is both an angst-ridden coming-of-age story of a gifted young woman, and a travelogue of sorts. Molly writes about her growing pains as a child with a neurological disorder, suffering through surgeries and medical interventions.

She shares discoveries and the logistical challenges of traveling in a wheelchair in Europe while on a writing scholarship. She struggles with faith, finds a home in Catholicism, and writes of her spiritual ties to her twin sister who died after birth. At the heart of it all, Molly shares her own changing relationship with cerebral palsy and the language with which we talk about our bodies. “The tectonic plates for who I am keep shifting.” she writes.

EXCERPT

—

For the last six months or so, whenever I’ve moved suddenly—stood up out of a chair, bent down to get my laundry from the machine, sneezed too hard in line at the convenience store up the block from my apartment—my back has spasmed, as if someone’s making a quick, hard fist around my spine and squeezing. At first, it was just a twinge, enough to startle me. These days, it knocks me off balance if I don’t brace for it first. And so I stretch more, and I stand and count to three before I step, or carry my coffee cup away from the table, or crouch down to put the dishes in the cabinet. I turn off the fan in the bedroom while I sleep, though it’s May in Mississippi and already eighty degrees. Better to wake up sweating than knotted and tremoring from some little chill.

They’re tiny, these adaptations. I suspect it took me months to notice I was making them. My life is built to flex unconsciously around new pain. I couldn’t even tell you what I used to do with the small space the spasms fill. This version of my life erases the last one, like a tape someone’s recorded over. Already, my memories begin reworking themselves to admit the spasms’ brief delay: two seconds tacked on to the end of everything, a touch more hurt.

I haven’t been to see a doctor because the change has so far been manageable. Because another dose of ibuprofen, a little less energy, and a slightly stronger ache to cope with isn’t going to hurt me, really. I haven’t been to see a doctor because I’m finishing graduate school and caught in the bureaucracy of going: no permanent address, shifting health insurance, too much in flux, and way too much to do.

I haven’t seen a doctor because I haven’t had a steady orthopedist since I outgrew the pediatric one I saw until I was eighteen. They treat cerebral palsy aggressively when you’re young, your brain and body at the height of their plasticity. There’s money to be spent on research and the promise of real progress to be made. They split your nerves, lengthen your tendons, splint your legs and map your changing gait with digital sensors that form points of light on the computer screen to indicate your muscles and your joints. This little constellation-self staggers the same blank orbit each year, getting taller. And then your body and brain have been reshaped as radically as medicine will currently allow, and you’re just who you are and there are the ensuing years to manage on your own.

I haven’t seen a doctor because my body has been mostly this version of itself for more than a decade now, and they’ve been mostly good years; I know the map of who I am and how I move by instinct, like home. I haven’t seen a doctor because they’ll want to alter something major, or they’ll tell me that there’s nothing to be done, that this is just my body’s slow erosion asserting itself beyond ignoring, and either way there’ll be a new geography to reckon with. I haven’t seen a doctor because I am afraid. I haven’t seen a doctor because there’s too much to be said for feeling familiar to yourself. This is all the truth.

Another truth: before I knew this body I knew another, nimbler one.

My very first body, the one untouched by major surgical intervention, exists only before my memory. For all intents and purposes, I wake into the world at the moment of its refashioning. My first clear recollection at four years old: somebody’s hand hovering over my face, the weird cage of the gas mask, a dense, false butterscotch mingled with the drug. No memory, of course, of what they did while I was under; they give you something to induce forgetting. But the body I woke up with, I know it served me well for years.

I know the surgeons clipped select nerves in my spinal cord, and thereby cut off at the pass the bulk of my brain’s bad commands to my muscles to contract beyond functionality or comfort. I know enough to know that I was born again then, in a looser shape, the one I first recognized as mine.

And it’s in that body that I spent my childhood. I moved stutteringly around my grade-school classrooms. I wore opaque, plastic leg braces that stopped at my calves and sneakers two sizes too big for my real feet that made me look like a girl playing dress-up as a circus clown. I never played tag or kickball. But I could slowly climb the stairs to the splintering wooden castle and go down the slide. I could haul myself up to the monkey bars and swing along them just long enough to fall and split my lip like children do. The cut there bled a bright and normal red that made my mother woozy while they stitched it up. There isn’t any scar.

—

Places I’ve Taken My Body: Essays

Indispensable essays on the body, mind, and spirit by Molly McCully Brown, author of the acclaimed poetry collection, The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, a book the New York Times described as “part history lesson, part séance, part ode to dread. It arrives as if clutching a spray of dead flowers. It is beautiful and devastating.”

Indispensable essays on the body, mind, and spirit by Molly McCully Brown, author of the acclaimed poetry collection, The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, a book the New York Times described as “part history lesson, part séance, part ode to dread. It arrives as if clutching a spray of dead flowers. It is beautiful and devastating.”

In seventeen intimate essays, poet Molly McCully Brown explores living within and beyond the limits of a body―in her case, one shaped since birth by cerebral palsy, a permanent and often painful movement disorder. In spite of―indeed, in response to―physical constraints, Brown leads a peripatetic life: the essays comprise a vivid travelogue set throughout the United States and Europe, ranging from the rural American South of her childhood to the cobblestoned streets of Bologna, Italy.

Moving between these locales and others, Brown constellates the subjects that define her inside and out: a disabled and conspicuous body, a religious conversion, a missing twin, a life in poetry. As she does, she depicts vividly for us not only her own life but a striking array of sites and topics, among them Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the world’s oldest anatomical theater, the American Eugenics movement, and Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University. Throughout, Brown offers us the gift of her exquisite sentences, woven together in consideration, always, of what it means to be human―flawed, potent, feeling.

“In her first collection of prose, Brown, a poet and writing instructor at Kenyon College, eloquently, often wittily describes a mostly wheelchair-bound life lived with pain and the places, emotional and physical, to which she has traveled. Brown is a writer to watch…”

Heartfelt and wrenching, a significant addition to the literature of disability. KIRKUS REVIEWS

“Poet Brown (The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded) explores living with cerebral palsy in her fine prose debut … Brown’s work leaves readers with a lyrical look at living within the confines of the body.“ PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

“Places I’ve Taken My Body will strike chords in anyone who’s ever questioned their faith, been challenged by their body, or who has ever been vulnerable—which is to say, all of us.” FOREWORD REVIEWS (May/June issue)

First serial in: The Paris Review, The Yale Review

—

Molly McCully Brown is the author of the poetry collection e Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, which was named a New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2017, and coauthor, with Susannah Nevison, of In the Field Between Us, a correspondence in poems. Her poems and essays have appeared in e New York Times, Oxford America, Paris Review, Tin House, Yale Review, and elsewhere. She lives in Gambier, Ohio and teaches at Kenyon College.

Find out more about Molly on her website https://www.mollymccullybrown.com/places-essays

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing