My Birth Father’s Double Life

Growing up adopted, I often fantasised about my back story. The scant information the social worker gave my parents, shortly before they took six-week old me home, provided only the barest of bones:

Growing up adopted, I often fantasised about my back story. The scant information the social worker gave my parents, shortly before they took six-week old me home, provided only the barest of bones:

My birth mother was ‘creative’; her mother, my biological grandmother, was uncommonly supportive. My birth parents wanted to marry and keep me but they couldn’t because my birth father was already married to someone else.

My imagination eagerly filled in the blanks. How could it not? The origin story is one of the most powerful and enduring subjects in literature and mine was made more enticing by the veil of secrecy the state draped over it. For years I nurtured a fantasy that I was a Kennedy.

Not that I seriously believed it – if I had, questions about my history wouldn’t have nagged at the back of my brain the way they did until the mid-1990s, when my first pregnancy brought them roaring to the fore.

I did my best to stifle them. Such thought felt like a betrayal to the parents who raised me, parents who always said they’d help me search, if I wanted, but who I knew would rather I didn’t (want to). Moreover, searching was difficult. Since my marriage in 1990, Europe has been my home. My files were in Massachusetts, where I was born and raised. They were also sealed by court order, a standard practice. I had no legal right to them.

But my curiosity persisted, impervious to all rational objections. In 2001, I read on an adoptee rights website that I could get a copy of my adoption papers, albeit only after they’d been scrubbed of identifying information: surnames, towns, etc. From Brussels, where we were living, I sent for mine and received back 14 single-spaced pages of interviews with my birth mother Lynne, her mother Christine, and my birth father Jim. Despite shattering my fantasy – there is no Kennedy brother named Jim –, they were a riveting read. Think Jane Eyre set in New England just before the sexual revolution. Jim’s wife, the one he’d originally said was dead, even does a cameo as the mad woman in the attic or, more precisely, ‘in a mental institution in another state’ and thereby beyond the reach of the divorce papers with which Jim is desperate to serve her.

It’s a lie, of course. Jim has been leading a double life for the better part of two years. The big reveal came three weeks after my birth and was so simply brought about that I can only marvel that the jig lasted as long as it did. Lynne’s friend got Jim’s home phone number from the receptionist at the store where he worked, called it, and Jim’s wife answered: cue the penny dropping.

I was gobsmacked, as I expect most readers today would be, that any woman could date a man for a year, get pregnant, and carry the baby to term, without knowing his home phone number, but it raised no eyebrows with anyone at the time, not even the social worker. The past really is a foreign country.

Double lives are the stuff of soap operas and spy thrillers. Jim was a car tyre salesman from the Boston suburbs, average as mashed potatoes. His relationship with Lynne was a traditional courtship, not some torrid love affair. Had he just been after sex, surely there were easier, more productive ways to go about it.

I wonder whether the situation was one he crafted or bumbled into. I wonder how he managed to keep it going. Most of all, I wonder why he continued the charade long after it must have stopped being fun. Most men, upon learning their mistress was pregnant, would have either fessed up or dropped out of sight. Instead, Jim doubled down, driving from north of Boston to the elbow of Cape Cod, three nights a week, to stay with Lynne throughout most of her pregnancy. At Christmas, he gave her a diamond engagement ring. When she gave birth, he visited every day in hospital – though he avoided looking at me. He met with the social worker. Was he a fantasist, believing the lies he told, or was he really trying to find a way to marry Lynne?

The latter would have been difficult. Divorce, in the mid-1960s, came with stigma and harsh financial penalties, particularly in Massachusetts. Jim probably earned enough to support a decent lifestyle for one household, but he would have struggled to support two. He would certainly have lost custody of his two-year-old daughter and risked the possibility of never seeing her again. Perhaps he sacrificed the daughter he didn’t know, in order to keep the one he knew?

I’m not surprised that Lynne fell for his deception. She was thoroughly besotted. Furthermore, it’s easy to understand why a nice girl from a respectable family, in such a vulnerable position, would want to believe that the father of her unborn child was going to save her. It’s worth noting that neither her mother, nor her roommates, who seemed more worldly-wise than Lynne, questioned Jim’s sincerity, at least, not until after I was born.

The social worker had suspicions. These are subtly expressed, mostly through an overabundance of attribution in the portion of the papers devoted to Jim’s interview compared to those featuring Lynne and Christine. The string of he saids attached to every statement become red flags or question marks. No doubt the social worker had seen every variation of this human drama, a dozen times over, and recognised patterns, but it’s also true that she wasn’t the impartial judge she pretended to be. Facilitating adoptions was her business. It was in her interests for Jim to be a scoundrel.

The social worker had suspicions. These are subtly expressed, mostly through an overabundance of attribution in the portion of the papers devoted to Jim’s interview compared to those featuring Lynne and Christine. The string of he saids attached to every statement become red flags or question marks. No doubt the social worker had seen every variation of this human drama, a dozen times over, and recognised patterns, but it’s also true that she wasn’t the impartial judge she pretended to be. Facilitating adoptions was her business. It was in her interests for Jim to be a scoundrel.

I know this story has the makings of a novel.

In the 15 years since I got my papers, adoptee rights organisations have pushed to persuade American states to grant adult adoptees access to their records. In 2010, shortly before my husband, children and I moved from Brussels to the UK, I was able to get a copy of my original birth certificate. This led to a reunion with Lynne, who sadly died in 2013. Thanks to her, I have enough information to track Jim down, but I’ve chosen not to, mostly for reasons of self-preservation. It’s been my experience that people whose relationship with the truth is as casual as Jim’s generally leave a trail of human wreckage behind them.

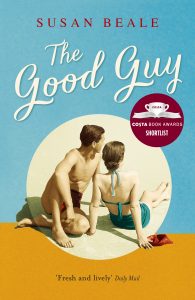

Besides, meeting him won’t give me what I most crave: a peek inside his head, unfiltered and without spin, to his thoughts in the months leading up to my birth to understand what he was hoping to achieve, and how he felt when it was over. Only fiction can do that. I made the most of it when writing my novel, The Good Guy.

I like to think I inherited Jim’s imagination, minus the penchant for deception. He has my undying gratitude. Because of his actions, I was raised by a wonderful Dad who let me know in a thousand ways that I was worthy of respect and love, which is the most precious gift any father can give a daughter.

—

Susan was raised on Cape Cod, lived in Belgium and France, and now lives in the Wells, Somerset. Susan has worked as a journalist and editor in the US and Europe. She is a former competitive figure skater. She is a recent graduate of the Bath Spa MA in Creative Writing. The Good Guy is her first novel.

Follow her on her Twitter @terminal_expat

SHORTLISTED FOR THE COSTA FIRST NOVEL AWARD 2016

A deeply compelling novel set in 1960s suburban America for fans of The Engagements and Tigers in Red Weather.

Ted, a car-tyre salesman in 1960s suburban New England, is a dreamer who craves admiration. His wife, Abigail, longs for a life of the mind. Single-girl Penny just wants to be loved. When a chance encounter brings Ted and Penny together, he becomes enamoured and begins inventing a whole new life with her at its centre. But when this fantasy collides with reality, the fallout threatens everything, and everyone, he holds dear.

The Good Guy is a deeply compelling debut about love, marriage and what happens when good intentions and self-deception are taken to extremes.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (3)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- Suggestion Saturday: April 29, 2017 | Lydia Schoch | April 29, 2017

What a story! I wonder why your birth mother thought your birth father didn’t want to give her his telephone number? It’s hard to imagine not being curious about that, but I’m sure she had a reason for that. 🙂

Yeah, that was a red flag for me, too, but Lynne never questioned it, neither did her mother or any of her friends. Men called women back then; not the other way around. Eventually, she had his work number, which he claimed was the easiest way to reach him. Also, from what I understand, he was in regular contact. She never felt ignored or unable to reach him.