On Writing Eve Bites Back: An Alternative History of English Literature

Eve Bites Back, in essence, explores what it takes to create literature if you are a woman – and is rooted in my belief that we can and should consider lives as well as works. Not everybody agrees, arguing that the ‘biographical turn’ leads inexorably to sexism, salacious anecdotes displacing serious textual analysis. I have a lot of sympathy with those who are wary of life-writing, but here are some of the reasons why I think it’s still worth doing!

Eve Bites Back, in essence, explores what it takes to create literature if you are a woman – and is rooted in my belief that we can and should consider lives as well as works. Not everybody agrees, arguing that the ‘biographical turn’ leads inexorably to sexism, salacious anecdotes displacing serious textual analysis. I have a lot of sympathy with those who are wary of life-writing, but here are some of the reasons why I think it’s still worth doing!

It is futile (although it is often done) to attempt to write Julian of Norwich’s life according to the template of the Great Male Authors of later centuries. It is racist (although it has been done) to write enslaved African American Phyllis Wheatley’s life according to the template of the upper-class White Lady Author. In writing women’s literary lives, we often need to ask different questions, explore different archives, look at familiar things from different perspectives. But I believe it is worth attempting, for it both honours women for writing despite and because they were born female and begins to answer the question: why so few?

This is not to say it isn’t challenging. Often the documents are simply not there and what we want to know remains well hidden. But this is true for many men. The surprising fact is that there is often just as much information about female authors as there is about male authors – and equally, some of the most canonical writers in English Literature (Shakespeare and Milton) test the practices of the conventional biographical project almost to destruction.

For Shakespeare, the archival cupboard is very, very bare, with almost no documents to tell us anything about William’s personal life. In fact, there are no letters at all, even to the man let alone from him. We have to build a life from some references, made by others, to his professional career (‘upstart crow’), from a few legal documents (‘tax avoider’) and the infamous bequest of his second-best bed to his wife in his will. We get an upstart crow tax avoider who hates his wife.

For Milton, in contrast, the cupboard is full. But what looks like archival riches, five volumes and counting of Life Records, turns out to be a mirage. Milton, or people close to him, made very sure that only certain kinds of documents would survive, skewing the archive to create the picture of an exclusively public life. Not only are there no letters to his three wives, or to his three daughters. There are none to his brother or father. None of this has stopped life-writers and critics in their tracks.

Nature and biographers abhor a vacuum – so we fill it, reading from literary texts to the life and back again. It is how we do it that matters. Here’s Harriette Andreadis writing about Sappho’s reputation and the recovery of her poems. Both are: ‘fraught with the complexities of informational lacunae and textual instability, so much so that the myths of Sappho soon overtook Sappho the poet and Sappho the person.’ In short, each era has remade Sappho in its own image, a phenomenon Monique Wittig and Sande Zeig underlined wittily: the entry for Sappho in their Lesbian Peoples: Material for a Dictionary (1979) consists of a blank page to be filled in by the reader.

As we fill in that blank page, I believe it is vital to show our workings. For starters, it matters which version of the text is being talked about, which moment in a lifetime is under consideration. Take Shakespeare’s Hamlet, a play that existed in (at least) three very different printed versions during the playwright’s lifetime. Add the actual moment(s) of creation and revision, the labour of reproduction, in this case the various printings, not to mention performances of the play(s), and the timeline not only begins to stretch but becomes cluttered with Hamlets – in preparation, in printing, in revision, in performance.

Not all of them can be a reaction to the death of William’s son or father, the two most popular biographical interpretations, with Shakespeare’s closet Catholicism a close-running third. Life and literature are more complicated than that. I want to consider these women’s lives, even when it is hard to do so, especially when it is hard to do so. In writing these chapters, I have foregrounded the fragmentary nature of what has survived – the torn pages, the lost works, the missing decades, the suppressed ideas, the births and deaths, the journeys and the love affairs about which we know nothing. And I want to explore difference as much as similarity, because there is no single story of ‘women’s writing’. One woman’s life and work can never, should never, stand for all women’s lives and works.

—

Anna Beer is a cultural historian and biographer. She is author of Sounds and Sweet Airs: The Forgotten Women of Classical Music and Patriot or Traitor: The Life and Death of Sir Walter Ralegh, as well as biographies of Bess Throckmorton, William Shakespeare and John Milton. She is a Visiting Fellow at Kellogg College, University of Oxford.

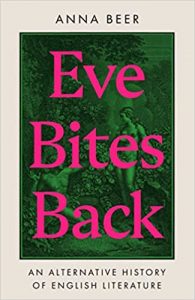

EVE BITES BACK: AN ALTERNATIVE HISTORY OF ENGLISH LITERATURE

Anna Beer investigates the lives and achievements of eight women writers, uncovering a startling and unconventional history of literature

Anna Beer investigates the lives and achievements of eight women writers, uncovering a startling and unconventional history of literature

‘Essential reading.’ Claire Tomalin

Warned not to write – and certainly not to bite – these women put pen to paper anyway and wrote themselves into history.

From the fourteenth century through to the present day, women who write have been understood as mad, undisciplined or dangerous. Female writers have always had to find ways to overcome or challenge these beliefs. Some were cautious and discreet, some didn’t give a damn, but all lived complex, eventful and often controversial lives.

Eve Bites Back places the female contemporaries of Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton centre stage in the history of literature in English, uncovering stories of dangerous liaisons and daring adventures. From Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Aemilia Lanyer and Anne Bradstreet, to Aphra Behn, Mary Wortley Montagu, Jane Austen and Mary Elizabeth Braddon, these are the women who dared to write.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing