On Writing Through the Lens of Trauma Memory

On writing through the lens of trauma memory

On writing through the lens of trauma memory

by Carly Schabowski

The role of memory in historiography even now remains a live debate, with questions around signposting to readers, the favouring of written accounts over living memory and the extent of the need for verification.

For memory to be a principal lens for recreating history is, though, different from allowing it to ‘pose’ as fact under certain historiographical conditions – it is no longer just oral history or autobiography; it is reworking history’s boundaries, or the boundaries of what is seen as ‘real’ history. I choose memory and trauma memory in my novels almost paradigmatically, as the best lens through which to view the past; in part because I want my reader to consider history not as an objective historical truth, revealed through scientific enquiry, but as a collection of evaporating memories, ever distorting and blending.

Where using memory as historical evidence is a way of thinking about memory, I want my reader to think with memory, to recognise it as both our closest link to the past and one of our most fraught. Memory, and its distortions, fragmentations and omissions provides, in its own way, our most ‘real’ picture of history. It is for each of us our only direct lens into the past. The way in which memory re-versions itself, individually and collectively, effects its own organic narrativization of the past.

The previous century was uniquely affected by trauma; the experiences and effects of WWI, WWII, and the Cold War have reworked our understanding of our recent past, and how we perceive it. The history of WWI has largely been handed to the traumatised voices of front-line accounts, their mnemonic scarring showing through in allusive and allegorical poetry, uncomfortable satire or understatement. WWI was called the war to ‘end history’, and indeed it was in the intangible obscenity of the experience that turned its history into a particularly literary one.

As with individual experiences of trauma, there was something in the raw emotion of WWI that required preserving, something real beyond the truths that constituted it. Similarly, the unique trauma of the Holocaust led historians to accept the historiographical legitimacy of survivors’ memories and witness testimonies to an unprecedented degree: the object of history was self-consciously too difficult to comprehend, so we were compelled instead to preserve it, like an unprocessed trauma memory, quarantined in history. And there was an element of collective processing in how these subjective narratives came to write the history books; Saul Friedländer, for example, claimed that the emergence of trauma memory within historical discourse, and literature, was due to the fact that after a period of time, repressed memories came to the fore, and subsequent generations were then drawn into the uncovering and understanding of these traumatic memories almost to resolve an aspect of their ancestral identities.

These collective traumas, and the need to process them, made fresh demands and asked new questions of history; they demanded that what we preserve of the past, needed to broaden, or to change; that the reality of the experience could not be captured in facts alone.

Allowing trauma memory into the historical canon requires a reframing of how we view the past. It suggests a past that is somewhat more than a single objective reality to be chiselled into form by historical enquiry; it suggests a past made up of a collage of discordant subjective experiences. The reliving of trauma provides a visceral link to the emotional, more than the factual, reality of the past.

That trauma compels reliving – and that trauma memory has the capacity to preserve emotional vividness – makes it a powerful link to the past as a lived reality. The ghosts of the past do not just want to be seen; they want to be heard too. As Morris wrote of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, it ‘…is a novel based on the personal recollections and experiences of one man. It is not, and has never claimed to be, an official history. If it inspires people to engage with the terrible events of the Holocaust more deeply, then it will have achieved everything that Lale himself wished for.’ In reinvigorating the voices of the past, we cannot discount them on the basis of their subjectivity and apparent inaccuracy.

With utilising memory and trauma memory as a lens within my novels, it has afforded me a means to construct an inherently subjective view of the past – a collage of realities and a narrative truth rather than an objective historical truth. And this has also led me to the limits of memory – failing or diminished memory; circumstances where memories diverge in the extreme and, perhaps, in this way show their true colours.

An historical fiction author’s choice of using traumatic experiences to look back at the past, is of course fraught with danger, mainly that the trauma is dealt with responsibly, and not used as a mere plot point in the story. Further, she must acknowledge where these memories came from, and understand that they may become part of another lens, that of the collective memory. But if used with the care and attention it so deserves, writing through the lens of trauma memory, and memory as a whole, can provide a gateway into a wider understanding of lived historical experiences.

—

Carly is the USA Today bestseller of historical fiction novels The Ringmaster’s Daughter, The Watchmaker of Dachau, The Rainbow and The Note.

She lives in a tiny cottage in Oxfordshire, with barely enough room to swing a cat. Yet, she has managed to dwell in such a hobbit-type abode for some years with her two dogs, who keep her company as she reads, writes, eats chips, and drinks the occasional gin.

Her interest in WWII history spans from a familial connection and inspired her to complete a PhD regarding the author’s responsibility to historical fiction. Whilst an achievement, she gained 20 lbs, and became a hermit.

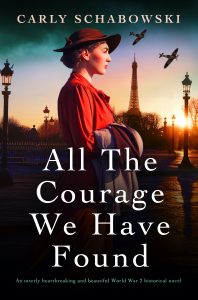

ALL THE COURAGE WE HAVE FOUND

France, 1942: An unforgettable, heart-wrenching and utterly unputdownable World War Two novel about one woman’s bravery in the face of darkness, and her heartbreaking decision to risk everything to do the right thing…

France, 1942: An unforgettable, heart-wrenching and utterly unputdownable World War Two novel about one woman’s bravery in the face of darkness, and her heartbreaking decision to risk everything to do the right thing…

As Kasia creeps out of the farmhouse in the dead of night to transmit an urgent message, her heart pounds in her chest. Gripping her radio tightly in her hand, she feels a terrible sense of dread. She knows that this message could be the one that finally leads the Nazis to her…

Crouching in the shadows, with trembling fingers she turns the dial on her radio and hears the familiar crackle of static. Shaking, she quickly taps out her message and, holding her breath, she waits in the darkness.

Suddenly, she sees a quick flash of light out at sea. Her message has been received by the Allied boats; now they know it’s not safe to come ashore tonight.

As she looks back towards the little farmhouse, her heart catches in her throat. Inside, the two people she loves most in this world are sleeping soundly. Because while Kasia knows her messages might save thousands of soldiers, she also knows that her radio signal could bring the Germans terrifyingly close, perhaps even straight to Hugo and Elodie…

A totally heartbreaking and gripping wartime novel of courage and of the endurance of the human spirit. Perfect for fans of The Tattooist of Auschwitz, When We Were Yours and The Alice Network.

BUY HERE

Category: On Writing