Openhearted Listening To The Stories Of Others, Including Victorian Women Artists

Openhearted Listening To The Stories Of Others, Including Victorian Women Artists

One of my favorite writers, Brené Brown, endorses what she calls “openhearted living.” When I hear that phrase, I envision spreading my arms and taking in what is present around me, fearlessly and with curiosity. This stance isn’t second nature. I grew up in a house with waves of tension, words left unspoken, and daily uncertainty.

I kept my antennae up for the next explosion—and I was always braced against it. This was an understandable adaptation for me as a child; but later I realized how this defensive strategy closed my heart to the intriguing surprise, to deeply felt joy and sorrow, and to other people’s stories.

As a writer, I’ve come to see that it is important to not brace against what’s incoming, but to open myself to it, to let it in, to let it shape my thoughts, to let it affect me, and even wring my heart. I’ve written six books now—but the ones that have succeeded all came out of stories that clutched at me and wouldn’t let go, often for years afterwards.

My third Victorian mystery, A Trace of Deceit (William Morrow Dec 2019), began in part from my work at Christie’s auction house in New York, back in the scandal-ridden 1990s. I had been hired to buy media space for their ads, but I’d never had an art history course, so after I arrived I gave myself a crash course on art so as not to appear an idiot.

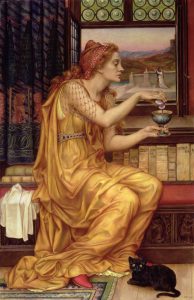

The Love Potion, 1903; by Morgan, Evelyn De (1855-1919); oil on canvas;

This meant spending time at the Metropolitan Museum in Central Park. (I know, forehead to brow and melodramatic sigh at the sacrifice.) I rapidly identified my favorite rooms and artists, one of whom was Evelyn de Morgan (1855-1919), even before I heard her surprising backstory.

Born Mary Evelyn Pickering, de Morgan’s paintings, particularly of women, are lush, visually stunning, and easy for the naïve viewer to love. But—no joke—when young Mary first began to study painting, her mother—who wanted “a daughter, not an artist”—paid Mary’s art instructor to discourage her, to tell her that she wasn’t talented.

That story grabbed me somewhere under the ribs. Like other Victorian women artists, including Kate Greenaway (for whom the Greenaway medal for book illustration is named), Elizabeth Rossetti and Laura, Lady Alma-Tadema, Mary’s access to serious art education was terribly limited. In London, there was the Finsbury School, which emphasized the training of artisans in wallpaper and tile rather than the creative “serious” arts of painting and sculpture, and where women were only allowed to take the night classes anyway (like the NASA engineer Mary Jackson in Hidden Figures).

There was the Royal Female School of Art, where women had to practice anatomical drawing from plaster casts and costumed mannequins—to prevent the women from seeing nude models (gasp!). Not until 1871, when the forward-thinking philanthropist Felix Slade opened the Slade Art School in Gower Street, did a school exist in England where women could study art on the same footing as men—with access to all the same classes, including anatomical drawing. Slade scholarships were based on merit, and in the early years, they were equally divided: two went to men, two went to women, one of whom as Mary Evelyn Pickering.

Pickering and other women painters became my inspiration. Over time, my heroine Annabel Rowe emerged in my imagination as a dedicated artist who entered the Slade in 1873. Her older brother Edwin was a brilliantly gifted painter, with every opportunity to succeed—but after power struggles with his overly ambitious father, Edwin became an opium addict and a convicted art forger. When he was released from jail, Edwin swore to Annabel that he had reformed, and he’d live within the law. But when he is murdered (in chapter 1) Annabel doesn’t know what to think. Was he telling her the truth, and someone from his past had come back to injure him? Or had he lied and returned to his dissolute habits?

Out of a desire to understand, and to find some emotional closure, Annabel begins to investigate Edwin’s life. With each discovery, she begins to realize that things she thought she remembered from their childhood and young adulthood weren’t wholly accurate. She begins to understand that there is a trace of deceit in all our memories, for memory isn’t like a painting; we all change, and our memories are shaped in part by the stories (and lies) we want to tell ourselves.

So this book is in part about the power of memory to shape our present and future. It also explores what it means to be “gifted”—the advantages it provides and the detrimental effects it can have upon a person and his family—and about what addiction does to others as well as to the addict. But ultimately, I wanted to suggest what happens when we cannot atone for our mistakes, and to offer the hope that perhaps by striving for openheartedness, we can achieve understanding that deepens us and broadens the sorts of stories we can hear and tell.

—

Karen Odden received her Ph.D. in English literature from New York University. She has taught English at UW-Milwaukee, published numerous essays on Victorian literature, and has set all her novels in 1870s London. Her first Victorian mystery, A LADY IN THE SMOKE (Random House/Alibi, 2015) was a USA Today bestseller.

Karen Odden received her Ph.D. in English literature from New York University. She has taught English at UW-Milwaukee, published numerous essays on Victorian literature, and has set all her novels in 1870s London. Her first Victorian mystery, A LADY IN THE SMOKE (Random House/Alibi, 2015) was a USA Today bestseller.

A DANGEROUS DUET won for Best Historical Fiction at the New Mexico-Arizona book awards, and her third, A TRACE OF DECEIT, set in the 1870s London art world, was published by William Morrow in December 2019. A member of MWA and Sisters in Crime, she lives in Arizona with her family and her ridiculously cute beagle-muse Rosy.

IG: @karen_m_odden

A TRACE OF DECEIT

From the author of A Dangerous Duet comes the next book in her Victorian mystery series, this time following a daring female painter and the Scotland Yard detective who is investigating her brother’s suspicious death.

From the author of A Dangerous Duet comes the next book in her Victorian mystery series, this time following a daring female painter and the Scotland Yard detective who is investigating her brother’s suspicious death.

A young painter digs beneath the veneer of Victorian London’s art world to learn the truth behind her brother’s murder…

Edwin is dead. That’s what Inspector Matthew Hallam of Scotland Yard tells Annabel Rowe when she discovers him searching her brother’s flat for clues. While the news is shocking, Annabel can’t say it’s wholly unexpected, given Edwin’s past as a dissolute risk-taker and art forger, although he swore he’d reformed. After years spent blaming his reckless behavior for their parents’ deaths, Annabel is now faced with the question of who murdered him—because Edwin’s death was both violent and deliberate. A valuable French painting he’d been restoring for an auction house is missing from his studio: find the painting, find the murderer. But the owner of the artwork claims it was destroyed in a warehouse fire years ago.

As a painter at the prestigious Slade School of Art and as Edwin’s closest relative, Annabel makes the case that she is crucial to Matthew’s investigation. But in their search for the painting, Matthew and Annabel trace a path of deceit and viciousness that reaches far beyond the elegant rooms of the auction house, into an underworld of politics, corruption, and secrets someone will kill to keep.

Buy the book here

Category: On Writing