Paintings in Novels

Everyone knows the image of The Girl with a Pearl Earring. The woman’s face turned half towards the viewer, the blue and yellow turban over her hair, the golden robe, and, at the centre of the image, the outsized earring itself. The original hangs in the Mauritshuis museum in The Hague. But that original is not what the majority of us have seen.

Most likely, when you think of that image, what you think of instead is the cover of Tracy Chevalier’s novel. Inspired by the “mass of contradictions: innocent yet experienced, joyous yet tearful, full of longing and yet full of loss” in the poster of the painting that she had on her wall, Chevalier reworked the image into a new art work. Four years later the conjunction of painting and novel had the power to beget an Oscar-nominated film. Those later works are what come first to our minds now.

Chevalier was hardly the first to borrow power from an existing work of visual art. To take two recent examples: The Da Vinci Code opens with a corpse posed as Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man in the Louvre; Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch centres on the theft of Carel Fabritius’s painting of the same name in the Frick Museum.

As the record visitors to the Frick’s 2014 exhibition of Fabritius’s painting showed, it adds an extra dimension to the reading experience to be able later to take a pilgrimage to see the original.

Like visiting a novel’s geographical setting, seeing the work of art at the heart of a novel lets us enter the world of the characters. We can stand in the gallery where those characters stood, though thankfully not experience the bombing Tartt’s main character Theo lives through, in the chaos of which he first acquires the painting.

Paintings come with their own history, emotions, meanings. They are a setting in themselves, on which a book can lean. For an author, referring to a painting can create a shortcut to expressing particular feelings or atmosphere. Drawing on an existing art work also creates a web of references across time that enriches and extends the world of the novel.

The painter of ‘The Goldfinch’ died in a gunpowder explosion; his painting, in Tartt’s story, is stolen in the aftermath of terrorist bomb. Coincidence? I think not. And so the tendrils of both works reach out into our minds.

It was the feelings a reference to a famous painting can create that led me to include several in my novel, The Storyteller.

I wanted to create a web of narrative contradictions, of things never being what they seem. The novel begins in a psychiatric ward, with two women confused about reality, unable to trust their perceptions of what is going on. The relationship between Iris, the ‘storyteller’ of my title, and Rachel, whose story she is telling, is fraught with conflict. A seam of betrayal – of love turning out not to be love at all – runs through both women’s lives. Creating that complexity was central to the way I wrote.

Yet despite knowing I had written that complexity into the character and narrative point of view, it was only when writing this piece that I realised quite how deeply the paintings that I chose reflect back these complications.

Early on, Iris compares Rachel to Titian’s ‘Venus’. I knew exactly what I was doing here. The difference between the louche Renaissance goddess and the weak girl on a hospital bed could hardly be less apt; we learn wariness about trusting Iris as a result. But then there were also the posters I placed on the hospital walls.

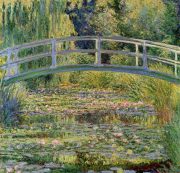

Early on, Iris compares Rachel to Titian’s ‘Venus’. I knew exactly what I was doing here. The difference between the louche Renaissance goddess and the weak girl on a hospital bed could hardly be less apt; we learn wariness about trusting Iris as a result. But then there were also the posters I placed on the hospital walls.  I choose to refer to Monet’s ‘The Japanese Bridge (The Water-Lily Pond)’ and Van Gogh’s ‘Still Life – Vase with Fourteen Sunflowers’ – both such well-known images the reader can picture them instantly even if the full names are unfamiliar. I intended the reference to be simple: bad reproductions of famous paintings are a cliché of a certain type of institutional setting, a crude attempt to ‘decorate’ a location that is characterised by pain.

I choose to refer to Monet’s ‘The Japanese Bridge (The Water-Lily Pond)’ and Van Gogh’s ‘Still Life – Vase with Fourteen Sunflowers’ – both such well-known images the reader can picture them instantly even if the full names are unfamiliar. I intended the reference to be simple: bad reproductions of famous paintings are a cliché of a certain type of institutional setting, a crude attempt to ‘decorate’ a location that is characterised by pain.

But now I realise the references do more than that. In The Storyteller, the images referred to are not the original paintings, but just flat copies, just as the women themselves are not living full human lives but merely existing. The waterlilies and the sunflowers may be lush, but the psychiatric ward the women are on is anything but. And, though both paintings are of the beauty of nature, the women are locked in the building, confined away from the world; and it turns out that even the paintings are nailed to the wall, an unnatural, brutal reality that again reflects the women’s experience.

But now I realise the references do more than that. In The Storyteller, the images referred to are not the original paintings, but just flat copies, just as the women themselves are not living full human lives but merely existing. The waterlilies and the sunflowers may be lush, but the psychiatric ward the women are on is anything but. And, though both paintings are of the beauty of nature, the women are locked in the building, confined away from the world; and it turns out that even the paintings are nailed to the wall, an unnatural, brutal reality that again reflects the women’s experience.

Little of that was deliberate as I wrote. Instead, the connotations of the paintings wove their way into my narrative even despite my awareness. The filaments of the web attached themselves to other images, and began to build into something that extended beyond my story. Looking back, I’m amazed by what came out. If that’s not an example of the magic of referring in a novel to a work of art, then I don’t know what is.

*************

Kate Armstrong graduated with a doctorate in English Literature from Oxford University and then become a management consultant in London.

Kate Armstrong graduated with a doctorate in English Literature from Oxford University and then become a management consultant in London.

Five years ago she had a severe breakdown that gave her the material and the space she needed to return to her literary roots. Her first novel, The Storyteller, was published on 2nd June 2016 by Holland House Books.

Read her blog at: www.katejarmstrong.wordpress.com

Follow her on Twitter @katejarmstr

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing