Taking Back the House By Elaine Neil Orr

The year I attended first grade, I lived with my family in a two-story house (the style is called a foursquare) in the West End neighborhood of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The house already seemed a bit run down. It had probably been a rental for some years. Among my most vivid memories is a small added room off of the living room, chilly in winter, where we watched the few television shows my sister and I were allowed. And a light-filled music room to the right of the living room where we practiced piano. It was my first year to take lessons. The year was a first in many ways: my first grade year, my first piano lessons, my first snow, my first memories in my parents’ home country, the United States. My home country, or so I believed, was Nigeria, where I was born and where my parents were missionaries.

The year I attended first grade, I lived with my family in a two-story house (the style is called a foursquare) in the West End neighborhood of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The house already seemed a bit run down. It had probably been a rental for some years. Among my most vivid memories is a small added room off of the living room, chilly in winter, where we watched the few television shows my sister and I were allowed. And a light-filled music room to the right of the living room where we practiced piano. It was my first year to take lessons. The year was a first in many ways: my first grade year, my first piano lessons, my first snow, my first memories in my parents’ home country, the United States. My home country, or so I believed, was Nigeria, where I was born and where my parents were missionaries.

I vividly remember the bedroom upstairs where my sister and I slept, in unadorned single beds and with metal dressers brought in from Baptist hospital. I did not think we were poor. We practiced stamp collecting and ate lovely dinners at night in the dining room. My parents were gods to me: capable, lofty, loving. Up the steep hill that is First Street in Winston, we perched in our minor kingdom. Walking with my sister to Brunsun Elementary was all downhill. I loved school. I was also capable, as it turned out.

And so I loved this large house with its ten foot ceilings and deep front porch and the diamond shaped glass between two upper-floor windows.

After a year of winter coats and leggings and my new school that ran beside Peter’s Creek, we returned to Nigeria and I didn’t see the house again for over fifty years. In my years of growing up, in Nigeria and the U.S., I lost ten houses and I loved all but two, a spit of a ranch house in Easley, South Carolina, where the curtains were plastic and there was no dining room, and a “missionary house” in Decatur, Georgia, through which missionary families circulated and everything seemed fake. I know the philodendron was. But the other houses I loved. My parents’ regal capacities were great. They were a bulwark against all sorts of trauma, including the Nigerian Civil War. And thus the houses were made sacred.

With a one-way ticket, I eventually left Nigeria and came to the U.S. The Winston-Salem house was the only home I had occupied in this country to which I felt attached. And yet I never went back to it. Or not until I decided to write a novel and set it in Winston and occupy that house again, at least in my mind.

Early in my jottings, I visited West End. It was easy to find the house at the corner of West End Boulevard and Jarvis Street. I could see it from I-40 business that cuts through town. One winter day, I parked on West End and walked along the meandering street to look at the house. In most ways it looked the same, not much worse for wear, painted blue—that was different. But the diamond window was still there and the towering hardwoods in the back and the deep front porch and the steps up to it and the banked yard with ivy across the front. One difference was a large fence enclosing the front yard. I continued to visit the house over a period of four years while I wrote the novel. Twice I happened to run into the owner—I never dared open the fence and enter and walk up to the front door to ring the bell. The fence was too formidable.

I tried to talk him into letting me see the house. Both times he refused. Something about how he was re-doing the interior and what a mess it was. Apparently the house had been subdivided into rental units. I wondered if he was growing marijuana in there. There was a basement I didn’t want to think about.

Maybe the marvelous switch-back stairs had been tampered with. Or the spacious dining room cut in two, or the open music room closed in as a bedroom. After the second refusal, I stopped trying to get in.

I was already in. Light was falling into the music room. It was a fall afternoon. When I looked out the front windows, out across the front porch, yellow leaves were falling across the yard.

I was already in the kitchen, leaning over that huge sink, with the old fashioned spigot, washing my hair, then rolling it in a towel and gazing out at Jarvis where a blue Impala with a white roof heading down the street where it would, of necessity, turn right onto Sunset and intersect First and then be required to go right towards town or left toward Baptist Hospital.

I was already descending the stairs for breakfast, those large deep brown, hard wood stairs that turned at the landing, a deep sense of contentment in my bones because my parents were below, preparing breakfast, and my older sister was kind and looked out for me and even if I was wearing a hand-me-down dress, my hair was clean and my teacher liked me and there was a boy at school who stood at the door to the classroom every morning and waited for me.

Already I was in the backyard, observing the jonquils dance in the spring breeze.

I had my house. Now to find my character. He showed up just when I needed him, humming a Buddy Holley tune.

—

Elaine Neil Orr is professor of English at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, where she teaches world literature and creative writing. She also serves on the faculty of the low-residency MFA in Writing program at Spalding University in Louisville. Author of A Different Sun, two scholarly books, and the memoir Gods of Noonday: A White Girl’s African Life, she has been a featured speaker and writer-in-residence at numerous universities and conferences and is a frequent fellow at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She grew up in Nigeria. Learn more at www.elaineneilorr.com, https://www.facebook.com/ElaineNeilOrr/, or https://twitter.com/elaineneilorr.

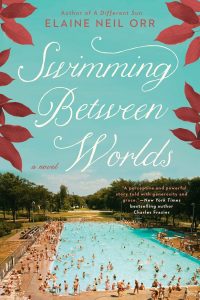

About SWIMMING BETWEEN WORLDS

From the critically acclaimed writer of A Different Sun, a Southern coming-of-age novel that sets three very different young people against the tumultuous years of the American civil rights movement…

From the critically acclaimed writer of A Different Sun, a Southern coming-of-age novel that sets three very different young people against the tumultuous years of the American civil rights movement…

Tacker Hart left his home in North Carolina as a local high school football hero, but returns in disgrace after being fired from a prestigious architectural assignment in West Africa. Yet the culture and people he grew to admire have left their mark on him. Adrift, he manages his father’s grocery store and becomes reacquainted with a girl he barely knew growing up.

Kate Monroe’s parents have died, leaving her the family home and the right connections in her Southern town. But a trove of disturbing letters sends her searching for the truth behind the comfortable life she’s been bequeathed.

On the same morning but at different moments, Tacker and Kate encounter a young African-American, Gaines Townson, and their stories converge with his. As Winston-Salem is pulled into the tumultuous 1960s, these three Americans find themselves at the center of the civil rights struggle, coming to terms with the legacies of their pasts as they search for an ennobling future.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing