Taking The Restricted View

Outwardly, Spain wears its complex history with disarming simplicity: in a village cemetery, a human thigh bone stands propped against the wall; a fading pencilled statement, apparently equally forgotten, records the arrival of Nationalist troops on the 20th day of September 1938; on the rubbish heap above the village, among the old tiles and bricks we’re searching for, we stumble across flock records from the 50s turfed out when they were moving the Town Secretary’s office and are stunned by the size of the flocks (they are so small), and by the fact that history has been so casually thrown away.

Outwardly, Spain wears its complex history with disarming simplicity: in a village cemetery, a human thigh bone stands propped against the wall; a fading pencilled statement, apparently equally forgotten, records the arrival of Nationalist troops on the 20th day of September 1938; on the rubbish heap above the village, among the old tiles and bricks we’re searching for, we stumble across flock records from the 50s turfed out when they were moving the Town Secretary’s office and are stunned by the size of the flocks (they are so small), and by the fact that history has been so casually thrown away.

We are here in southern Aragon because seventeen years ago we bought an old house in this village and although we live mostly in Wales we love to spend time here in Spain, quietly working on the house but also writing. And this place is a novelist’s dream, a craggy wild landscape, and wild and craggy stories to go with it.

Some of the stories have floated only slowly to the surface. Maybe because we’ve been around long enough now, or maybe simply because our neighbours, growing old, become more willing to speak of things that happened long ago. Our neighbour recalls his grandfather telling him what he witnessed of the last of the Carlist Wars – civil wars that moved across this landscape half a century before the Spanish Civil War of 1936.

But it is the latter war that dominates, particularly the long years afterwards when the resistance fighters, known as the maquis, went on hiding from the Guardia in the surrounding hills and sometimes in the houses of the village, including ours. There are traces of them everywhere round here: the ruins of the hydro-electric station they blew up, the pockmarks of bullets in the walls of a pill-box. The pine tree where people we know were held up and robbed in the 1950s. The house in the village where the young couple were found hanging from the eaves and the Guardia called it suicide but nobody believed it.

But it is the latter war that dominates, particularly the long years afterwards when the resistance fighters, known as the maquis, went on hiding from the Guardia in the surrounding hills and sometimes in the houses of the village, including ours. There are traces of them everywhere round here: the ruins of the hydro-electric station they blew up, the pockmarks of bullets in the walls of a pill-box. The pine tree where people we know were held up and robbed in the 1950s. The house in the village where the young couple were found hanging from the eaves and the Guardia called it suicide but nobody believed it.

One placid midsummer evening, under the grapevine, our friend Romualdo tells us how he was called up in 1938, aged just sixteen. He didn’t see any action but the dead bodies he passed near the Front Line still give him bad dreams. We sit quietly, taking this in. And then Romualdo moves on, to a rather jollier tale about the maquis who escaped from the lock up after someone smuggled a mattock through the bars. In the bar opposite, the villagers plied the Guardia with drink all night long and sang at the tops of their voices to drown the sound of the prisoner breaking through the wall.

Not surprisingly, I had the seeds of a plot long before I came to writing the novel. But when I started I found particular challenges lying in wait. First, I tend to get bogged down by factual detail so although I’m happy to do background reading I’m wary of research. Besides, I had a lot of information already at my fingertips from all the things we acquired with the house: saddles and ploughs, beds and petticoats and clogs, hayforks and mattocks and a yoke for the oxen.

The sounds that drift in through the open windows here have hardly changed since the 1930s, the most magical being the sheep bells and the high ‘hee-wit’ of their shepherd calling them. You can hear from the bells what the sheep are doing and how big the flock is.

These everyday details were what I wanted to build my story from, so I made my main protagonist a child of nine, a usefully in-between age for moving about below the politics and also – more to the point – beneath the radar of the hostile Guardia. Albi’s world is the world of implements and animals, his understanding of the big events is limited to what he overhears and what he thinks he observes. And when he starts carrying messages to the maquis, his limited understanding feeds his fear, and finally his resentment, with tragic results.

These everyday details were what I wanted to build my story from, so I made my main protagonist a child of nine, a usefully in-between age for moving about below the politics and also – more to the point – beneath the radar of the hostile Guardia. Albi’s world is the world of implements and animals, his understanding of the big events is limited to what he overhears and what he thinks he observes. And when he starts carrying messages to the maquis, his limited understanding feeds his fear, and finally his resentment, with tragic results.

The second issue I faced was the landscape of the Maestrazgo. It is so vast, so extreme, with its gorges and narrow fins of rock on which brooding vultures perch, its extraordinary buildings and secret villages. It is melodramatic, and there’s just so much of it. How could I convey this, having limited myself to telling the story through Albi’s consciousness? It’s so much easier to ‘tell’ a landscape through an outsider’s eyes and let rip with descriptions. But ordinary people are the essence of my story – the ones who don’t usually get heard – and country people don’t tend to voice what their landscape is, it’s too close for comment. Also, the vocabulary had to maintain the perched-on-the-shoulder illusion of looking at the world through Albi’s young eyes.

To begin with I chafed at these limitations but, as the storyline developed, the physical details made their way naturally into the narrative through the impact the landscape has on Albi – the steepness of the climbs, his fear of heights, the caves and secret valleys that lend themselves to hiding, the heightened awareness of being out at night after curfew when even the familiar becomes strange and threatening.

Writing this particular book has brought it home to me just how much a restricted viewpoint can free up and stimulate the writing process.

—

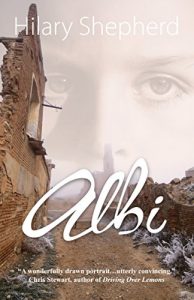

Hilary Shepherd has lived most of her adult life in Wales, running an organic farm for twenty years, and for the last fifteen years making oak windows, stairs and kitchens for building projects with her husband Nick. ‘Albi’ is published by Honno Press and is her third novel.

Hilary Shepherd has lived most of her adult life in Wales, running an organic farm for twenty years, and for the last fifteen years making oak windows, stairs and kitchens for building projects with her husband Nick. ‘Albi’ is published by Honno Press and is her third novel.

ALBI, Hilary Shepherd

Albi is nine years old when Franco’s soldiers arrive in the village and his life begins to change in confusing ways. It’s not clear quite who should be trusted and who should not. Some neighbours disappear not to be seen again, others are hidden from view in cellars and stables – like his brother, Manolo, who left long ago to join the resistance.

Albi is nine years old when Franco’s soldiers arrive in the village and his life begins to change in confusing ways. It’s not clear quite who should be trusted and who should not. Some neighbours disappear not to be seen again, others are hidden from view in cellars and stables – like his brother, Manolo, who left long ago to join the resistance.

Albi is charged with shepherding not just his own sheep, but also those of El Ciego who sends him on errands requiring a good memory and the ability to keep his mouth shut at all times.

Alberto, at 88, is haunted by what he did and what he may or may not have said. And then the daughter of his old friend Carlos turns up wanting stories of old times. Albi’s day of reckoning may be at hand.

“A wonderfully drawn portrait…utterly convincing.” Chris Stewart, author of Driving Over Lemons

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: On Writing