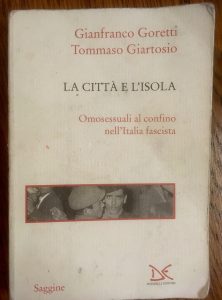

The City and the Island

c. Lou Abercrombie

Like most book ideas, Mussolini’s Island came to me by chance. I read an article on the BBC website which recounted a visit, in June 2013, of a group of LGBT activists to the tiny island of San Domino in the Adriatic Sea.

They were there to commemorate and raise awareness of a moment in history which has largely been forgotten – the imprisonment of a group of around 45 men from Catania, Sicily, detained by the fascist regime because they were, or were suspected of being, gay.

Taken from their homes, the men spent a year on San Domino – completely stranded, but left in relative freedom. Though it was a prison, their strange new home was a place where they could, for the first time, express their sexuality freely. This intriguing contradiction, along with the fascinating untold story, planted the idea of a novel in my mind.

The difficulties were obvious early on. There are hardly any records of what happened – most of the men were illiterate, and even had they not been, the stigma associated with their arrest meant they were unlikely to speak out, or leave behind any account of their experiences. I don’t speak Italian. I haven’t studied the second world war, or Italian Fascism, in any detail before. I was starting from the very beginning.

The first and most useful source I found was a small book called ‘La Citta E L’isola’ (the City and the Island), which traced the prisoners’ journey, from their lives in Catania, though their arrest and the year they spent on San Domino, and what happened to them afterwards. I was desperate to read it, but there is (as far as I know) no English translation. This tiny book, with its few grainy archive photographs, became my most important novel writing prop; though I couldn’t read it, I took it everywhere with me.

The first and most useful source I found was a small book called ‘La Citta E L’isola’ (the City and the Island), which traced the prisoners’ journey, from their lives in Catania, though their arrest and the year they spent on San Domino, and what happened to them afterwards. I was desperate to read it, but there is (as far as I know) no English translation. This tiny book, with its few grainy archive photographs, became my most important novel writing prop; though I couldn’t read it, I took it everywhere with me.

My Dad (who is learning Italian) and I spent painstaking months translating it, armed with nothing more than an Italian dictionary and google. It seems like a ridiculous approach, and perhaps it was, but in doing so, I learned something about the rhythms of the language, which began slowly to find its way into my dialogue.

I learned, too, that Sicily has its own dialect – almost Italian, but with regional variations. We picked up various slang phrases which would have been used frequently by my characters – men suspected of being gay, for example, were known collectively as ‘arrusi’.

Alongside this, I read books (thankfully in English) about Fascism, about the second world war, about Italy in the twentieth century. I pieced together as much as I could and wrote, fairly rapidly, a first draft of my book. I thought it was the final draft, but it quickly became clear something was missing. I had, in my frenzy of research and translation, forgotten something – I hadn’t visited either Catania or San Domino.

This seems so obvious, but it’s amazing how easy it is to overlook; how tempting it is to stick to the research and keep your head down. I was desperate to finish the book, and the idea of taking a week off to get on a plane to Catania, let alone a boat to San Domino, seemed unthinkable. But as soon as I did, I began to rewrite everything.

I started in Catania, where the arrusi had lived most of their lives. Walking through the crumbling, faded streets, between wide, elegant piazzas and dark, shadowed back streets, I wondered why so many of my scenes were set indoors. Why describe men sitting around a kitchen table when I could have my characters interacting here, in the city they had been forced to hide in?

It had so much character, and said so much about what they must have experienced. I found so many locations I had read about in La Citta E L’Isola: the railway arches the arrusi met beneath, the dance hall in which they gathered, even the prison and the hospital they had been taken to after their arrest, all came to life.

A little while later, I visited San Domino. I threw the trip together in a hurry; a complicated combination of trains, buses and ferries, and arrived bewildered, with no goal other than to get a feel for the place. I had brought La Citta E L’Isola with me, of course, and there was a strange feeling of having been there before as I explored the tiny wooded island I had read so many descriptions of.

One evening, sitting alone in a restaurant in San Domino’s tiny village centre, I went all the way back to the beginning. I reread the original BBC article on my phone, and something stood out in it I hadn’t noticed before. A man who lived on the island was quoted. They used his name, Attilio Carducci, and he remembered the prisoners who had come to the island.

One evening, sitting alone in a restaurant in San Domino’s tiny village centre, I went all the way back to the beginning. I reread the original BBC article on my phone, and something stood out in it I hadn’t noticed before. A man who lived on the island was quoted. They used his name, Attilio Carducci, and he remembered the prisoners who had come to the island.

I felt suddenly excited, and terrified. The article was three years old – he was, chances were, still here. My Dad texted encouragement; ‘it’s a small place, just ask around’, but how could I? He must be in his 90s – why would he want to talk to a strange English girl who had turned up on his doorstep asking questions about the past? I was only here to develop a sense of place – there was no need start bothering the locals while I did it.

Eventually, after a big glass of wine, I decided. I had travelled a long way, and it wouldn’t be easy to come back any time soon. My final edits were due in a few weeks – this was my last chance. I asked a waitress, and before I knew what was happening we were knocking on Attilio’s door, at 11pm. She didn’t seem to think he would mind.

Attilio wasn’t in, but he was the next day, when I went back alone. He answered the door, smiling and laughing and utterly unfazed, even when it became clear neither of us spoke a word of each other’s language.

Then an idea came to me – I handed him my battered, pored over copy of La Citta E L’Isola. He took it, and understood instantly why I was there, and what I was asking about. We scoured the island for someone who could act as a translator, eventually locating some friends of his, Luigi and Elena – who just happen to live in the building which had once been the arrusi’s prison.

Then an idea came to me – I handed him my battered, pored over copy of La Citta E L’Isola. He took it, and understood instantly why I was there, and what I was asking about. We scoured the island for someone who could act as a translator, eventually locating some friends of his, Luigi and Elena – who just happen to live in the building which had once been the arrusi’s prison.

For two days, the four of us ate lunches and dinners and drank in open air bars and talked about the arrusi, the island’s history, Italy’s fascist past and how they felt about it. I learned things I never could have found in my books, however much painstaking research I had done. I went away with an entirely new understand of the island, its history, and what it might have been like to live there. Suddenly, my battered, pored over copy of La Citta E L’Isola wasn’t just research – it was a passport.

Before I left, I asked Attilio to write his name in the book. I don’t know why, except that meeting him felt like the end of a long research journey – from painstakingly translating a book in my room in London, to sitting in a bar on a tiny Italian island with a man who remembered the events I had tried so hard to learn about from books.

That’s the thing about research – if you can, you should always follow your characters. Let them take the lead, and you never know where you’ll end up.

- La Citta E L’Isola is available to buy on Amazon here. And if you find an English translation, please, for the love of God, don’t tell me. (Or my Dad.)

—

Category: On Writing