The Creative Unconscious

There’s a lot to be said for writing to a plan or outline. Words emerge much faster if we know where our characters are going and what they’ll encounter along the way. But there’s a downside to approaching our work with an overly rational mindset. Too much order and we lose the capacity to amaze not only our readers but ourselves.

There’s a lot to be said for writing to a plan or outline. Words emerge much faster if we know where our characters are going and what they’ll encounter along the way. But there’s a downside to approaching our work with an overly rational mindset. Too much order and we lose the capacity to amaze not only our readers but ourselves.

Some people are sceptical about the unconscious; a concept, they think, that should have died with Freud. How can we know something and, at the same time, not know it? But if you’ve ever “forgotten” an appointment or had a “meaningful” dream, if you write half-asleep in the early morning, your unconscious is very much alive.

Although familiar with unconscious processes from my previous job and studies, I was unprepared for the extent of their impact on my fiction. During years of secret scribbling I delighted in the ideas that would arise unbidden while out walking or driving, my thoughts on other things or nothing at all. But, beyond that, I didn’t expect my unconscious to impinge in ways of which my conscious mind was unaware.

As Taylor Larsen wrote recently, we know our unconscious (or subconscious as some writers prefer) is doing its job when our characters take us by surprise. I won’t ever forget my shock at discovering, in an early draft of my debut novel, Sugar and Snails, the dreadful manner in which my protagonist’s father had betrayed a fellow soldier who was supposed to be his friend. Unlike ideas generated consciously, there was no sense that I could choose to accept or reject this part of his personal history. Although this skeleton in the cupboard made sense of the parenting decisions that moulded the main character, this wasn’t the main reason I built it into the novel. It was simply that, once the thought was formed, I couldn’t deny its truth. Regardless of how much I disliked what this character had done, it would have been dishonest to leave it out.

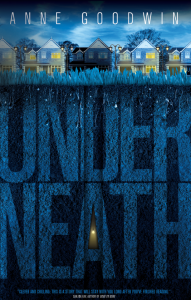

In giving my second novel the title Underneath, I was conscious of wanting to explore both the disturbing way my character, Steve, makes use of an underground room and the disturbance below the surface of a seemingly ordinary man’s mind. But it wasn’t until approaching publication that I appreciated how the empty space of the cellar reflects the empty space within him. Yet, given his unacknowledged vulnerabilities, it’s almost inevitable that he’d respond to the emptiness of the cellar in the same way he’s managed his psychological emptiness, by plugging the gap so he can fool himself it isn’t there.

Sometimes it takes a reader’s reaction for the author to recognise what her unconscious has slipped in. For example, my editor loved a scene in which Steve happens to be holding a knife when his girlfriend, Liesel, returns home. Given that the reader knows from the start he’s going to make the cellar a prison, the way this scene is written subtly increases tension. Yet in my mind, as in Steve’s, he’s only chopping vegetables for dinner.

Sometimes it takes a reader’s reaction for the author to recognise what her unconscious has slipped in. For example, my editor loved a scene in which Steve happens to be holding a knife when his girlfriend, Liesel, returns home. Given that the reader knows from the start he’s going to make the cellar a prison, the way this scene is written subtly increases tension. Yet in my mind, as in Steve’s, he’s only chopping vegetables for dinner.

In addition to plot and character, the unconscious shapes the language through which our story unfolds. Reading through the finished version of Underneath, I found multiple allusions to emptiness that I hadn’t noticed before. For example, early in the novel, when an estate agent shows him around the house he eventually buys, I was focused on the architecture when Steve refers to an alcove as “dead space”. But, although in denial about the impact of his deceased father, that dead space is central to Steve’s identity. A little later he comments, in relation to working nightshifts, “it wasn’t the work itself that was knackering, but the spaces in between”; both a straightforward reflection of his experience of fatigue and a hint of an area of personal difficulty of which he is oblivious.

Such symbolism can communicate directly from the unconscious of the author to the unconscious of the reader creating the perfect atmosphere for the particular story. Had I done this consciously it might have jarred; when our characters are free to tell it their way they can divulge more about themselves than even the author knows.

If the unconscious functions outside awareness, how can we ensure it doesn’t get out of hand? Is there a risk that, like a voluble child who discloses embarrassing information about her parents, our unconscious might give away more than we desire? As well as revealing the subtleties of our characters, will it betray the weirdness within us?

Although well acquainted with the peculiar machinations of my psyche, I was a little surprised to discover, placing the paperbacks of my two novels side-by-side, that both kick off with the narrator descending a staircase in their home. While each is an effective opening, as well as symbolically appropriate for the transition between different states of being, I’m still expecting an astute reader to confront me with what it reflects about some buried secret underneath my own personality, something I’d prefer others didn’t know.

—

After a twenty-five year career as an NHS clinical psychologist engaging with the insides of other people’s heads, Anne Goodwin has turned to fiction to explore her own. Her debut novel, Sugar and Snails, about a woman who has kept her past identity a secret for thirty years, was shortlisted for the 2016 Polari First Book Prize. Her second novel, Underneath, about a man who keeps a woman captive in a cellar, was published in May 2017. Anne is also a book blogger with a special interest in fictional therapists.

Website: http://annegoodwin.weebly.com/

Blog: http://annegoodwin.weebly.com/annecdotal.html

Twitter: @Annecdotist

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing