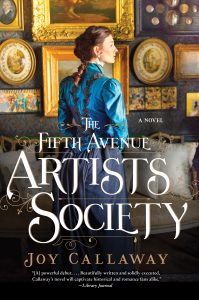

The Fifth Avenue Artists Society

I’m really into genealogy. I think I come by it honestly. My family as a whole is very interested in our history, and once you find one colorful story it’s hard to stop. Granted, I’ve hardly had to search for much—my grandma’s family sort of passes down anecdotes and then routinely talks about them, so, though we’re telling stories about people that could’ve been gone for a few hundred years, it seems like they’re living among us.

I’m really into genealogy. I think I come by it honestly. My family as a whole is very interested in our history, and once you find one colorful story it’s hard to stop. Granted, I’ve hardly had to search for much—my grandma’s family sort of passes down anecdotes and then routinely talks about them, so, though we’re telling stories about people that could’ve been gone for a few hundred years, it seems like they’re living among us.

Just the other day, Gran called to tell me that there was a new documentary on Myles Standish—we’re kin to his wives Rose and Barbara (he fell in love with both, married Rose first, and when she died married Barbara)—a few months back my mom and I spent weeks re-reading the diaries of The Fifth Avenue Artists Society’s main character, Ginny, and last week I had a conversation with one of my cousins about his research on his great-great-grandma, Nora Stanton Blatch. Though I’m not related to Miss Blatch, the fascination with our history clearly weaves through our line. And I suppose that’s how The Fifth Avenue Artists Society came to be.

Gran is the third of five Alevias in our family—my daughter is the fifth. When you walk in to her living room, you’re surrounded by portraits of the first two, and so one can’t help but ask after their story. The original Alevia was a VanPelt, of an old old New York family credited with helping settle the city, and her youngest daughter, named for her, was a concert pianist.

Virginia

Two of the other siblings were similarly artistic—Virginia (Ginny) was a writer and painter, Anne was a milliner—while Alice and Franklin pursued relatively ordinary roles, a teacher and salesman respectively. Only Alice married and had children, however, and so there’s always been this sort of wonder about them, especially because, though they lived in what my editor correctly termed “genteel poverty” they often interacted with famous artists of the time—Bernhardt Wall, Hamilton Revelle, among others—and one of our greatest family mysteries was born by their hands.

It would have been natural for the story to come from Alice’s perspective (Mae in the novel) because she’s my great-great grandmother and incredibly inspirational herself—she was a graduate of Hunter College and went on to be a great educator and mother—but when I sat down to write the story, I heard Ginny’s voice.

Perhaps it was because she was the writer—she penned a book, Washington Irving’s Footprints illustrated by Bernhardt Wall, wrote for the long-departed Bronx Review, and put together several anthologies of children’s books. She was also a world traveler in an era when traveling at all was rather tedious, particularly for a single woman, and when she finally came home to America for good, she helped create an artists colony in Lime Rock, Connecticut.

I wrote the book with a sense that I was being guided. There were several occasions where I found that things I’d incorporated fictionally were actually truth, and when our family history was a bit murky, I always felt a sense of clarity when I chose which path to direct the narrative. Ginny’s voice became all the more real when my mom and I found three years of her diaries for auction on a rare books site.

We tried to figure out where they’d come from, how they’d come to be sold, but there was no record. By that time, I’d already written The Fifth Avenue Artists Society, but it was so fascinating to read of her daily life, of the clothes she wore and the things she did—she loved to ride her “wheel” with friends and walk the High Bridge and organize women’s suffrage groups and, of course, write. It was also fascinating to read of her crushes, that she tried to mask as friendships even in her own diaries, and the way Alice’s beau and future husband, Arthur, got under her skin.

We tried to figure out where they’d come from, how they’d come to be sold, but there was no record. By that time, I’d already written The Fifth Avenue Artists Society, but it was so fascinating to read of her daily life, of the clothes she wore and the things she did—she loved to ride her “wheel” with friends and walk the High Bridge and organize women’s suffrage groups and, of course, write. It was also fascinating to read of her crushes, that she tried to mask as friendships even in her own diaries, and the way Alice’s beau and future husband, Arthur, got under her skin.

Even when weaving fiction in to fact, I tried to craft elements that seemed realistic to life. The Society is a figment of my imagination, and yet I can’t help but think they often participated in similar groups. It’s likely they weren’t as glamorous as John Hopper’s Fifth Avenue Society, but they still rubbed elbows with known artists. You can tell a lot about a person by their legacy, and for Virginia and Alevia and Anne (Bess), they’re remembered primarily for their art, which allows for the assumption that most of their life’s work was focused on shaping their craft. I tried to annunciate that passion in the novel, while allowing each of them different sources of motivation.

Their lives were all mostly lived in an unremarkable home in the Bronx, in the Mott Haven neighborhood, on the corner of Morris Avenue and 142nd Street. It was a family home built by their grandfather, an Irish immigrant, who sold his land on Fifth Avenue complaining of the racket made by the construction of Central Park and moved his children to what was then the country.

In 1924, Virginia wrote an article for the Bronx Review titled An Old Bronx Home. It was a lovely snapshot meant to illustrate Bronx life before and after the Civil War, but as I read the fond remembrances she included of her grandfather and her home, I started to understand how much she, too, had treasured our history, that it had inspired her just as it inspires me.

—

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post