The Forgotten Women of the War in the East

Isabel Wolff’s latest novel, “Shadows Over Paradise” is a poignant story about a Dutch girl and her family struggling to survive in a Japanese internment camp on Java. Isabel tells WWWB what drew her to this neglected part of World War 2 history.

Isabel Wolff’s novel Shadows Over Paradise

I’ve always had a fascination for the Pacific War. It began at 8, when I learned that my parents’ friend, Dennis, had been a POW in Burma. My mother told me, in hushed tones, that Denis had ‘suffered terribly’ and seen ‘terrible things’ although she didn’t want to say what those things might have been.

When I was 12, I read A Town Like Alice, set in occupied Malaya, a novel that has stayed with me all my life. And a few years later I watched, avidly, the TV drama series, Tenko, about a group of British and Australian women struggling to survive in a Japanese prison camp. These things came together in my mind and I decided to write a novel about the internment of women and children in the Far East.

There were many locations in which Ghostwritten could have been set: civilian men, women and children were interned right across the region in Singapore, Borneo, Malaya, the Philippines, China and Hong Kong. I chose to set it in the Dutch East Indies, on Java, where the Japanese camps were the most numerous. They were also, by and large, the worst.

As I planned the story I read history books about the period and scholarly articles; I visited survivors’ websites and read their accounts. I interviewed two elderly women who as children had been interned on Java and still vividly remembered the daily privation, brutality and fear.

I went to Java and saw the places in Jakarta (formerly Batavia) and Bandung where thousands of women had been interned. And as I stood in the Dutch War Cemetery and gazed at the white crosses for women and children that stretched away from me in all directions I was saddened to think how little their suffering is known. For the truth is that the male/military/POW narrative has come to define the story of the War in the East.

I wondered why this should be. Perhaps it’s because the Thai Burma ‘Death Railway’ was so ‘epic’ and monstrous, and has been dramatized with vivid horror in films such as Bridge on the River Kwai. More likely it’s because the soldiers had their army, their regiments and their comrades to extol their courage, and to make sure that their story was known.

I wondered why this should be. Perhaps it’s because the Thai Burma ‘Death Railway’ was so ‘epic’ and monstrous, and has been dramatized with vivid horror in films such as Bridge on the River Kwai. More likely it’s because the soldiers had their army, their regiments and their comrades to extol their courage, and to make sure that their story was known.

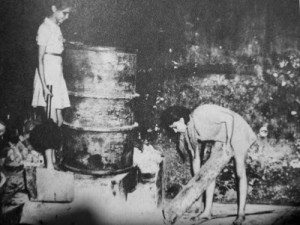

Yet the same number of civilians – 130,000, mostly women and children – were also imprisoned by the Japanese. These were Dutch planters, missionaries, civil servants and teachers who after the fall of Java were herded into hundreds of concentration camps. Like the POWs, the civilian prisoners suffered starvation, forced labour, cruelty and death. Yet they have had no-one to speak up for them.

This became apparent to me when my novel came out in the UK. One of the most common responses from readers was: ‘I had never heard about this.’ Perhaps this wasn’t so surprising, I reflected, given that you now have to be over 45 to remember Tenko. There was the film, Paradise Road, about a group of American and Dutch women in a camp on Sumatra, but that was back in 1997.

Since then no films or novels have focused on the civilian story, ‘though writers and directors continue to be fascinated by the suffering of the military men. This year alone there have been two Hollywood films – The Railway Man and the soon-to-be-released Unbroken about the Olympic runner and Japanese camp survivor, Louis Zamperini.

Since then no films or novels have focused on the civilian story, ‘though writers and directors continue to be fascinated by the suffering of the military men. This year alone there have been two Hollywood films – The Railway Man and the soon-to-be-released Unbroken about the Olympic runner and Japanese camp survivor, Louis Zamperini.

There has also been Richard Flanagan’s magnificent, Man Booker prize-winning novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North. I felt proud to be writing about what these women and children had been through. Yet as more reader comments came in, the ones that surprised me the most were: ‘I had never heard about this – and I’m Dutch!’

Dutch friends tell me that in Holland this part of wartime history is not widely taught, compared to the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, and the Holocaust. In their memoirs the internees who were repatriated to Holland in 1946 tell of further alienation in which, far from being welcomed back to the mother country, they were bitterly resented. Because they were emaciated – most had lost 30% of their body weight – they were given extra food coupons.

In grocery shops they would get sharp looks and sharp remarks. ‘Why should we look after you?’ was a frequent cry. ‘While you were sunning yourselves in the tropics, we had the Nazis!’ After all, the Dutch had themselves been starved during the terrible ‘Hunger Winter’ when the Germans blockaded northern Holland for six months. Little wonder then that there was no compassion for these ‘pampered colonials’ who were widely referred to as ‘Uitzuigers’ or ‘leeches’.

In grocery shops they would get sharp looks and sharp remarks. ‘Why should we look after you?’ was a frequent cry. ‘While you were sunning yourselves in the tropics, we had the Nazis!’ After all, the Dutch had themselves been starved during the terrible ‘Hunger Winter’ when the Germans blockaded northern Holland for six months. Little wonder then that there was no compassion for these ‘pampered colonials’ who were widely referred to as ‘Uitzuigers’ or ‘leeches’.

It was as though there had been two, quite different wars, and the repatriates soon learned not to talk about theirs. Their war was the war of starvation, dysentery, savage beatings and bamboo fencing. In time, survivors began to tell their story in memoirs, all with titles redolent of a lost Eden: Dark Skies Over Paradise; Java Lost and Stolen Childhood. And now there’s a novel, Shadows Over Paradise which has their ordeal, and their courage, at its heart.

—

Isabel Wolff’s latest novel, Shadows Over Paradise (published in the UK as Ghostwritten) is published by Random House Inc. in paperback and on Amazon Kindle on February 10th.

You’ll find more writing and publishing advice on Isabel’s Facebook Author Page https://www.facebook.com/isabelwolffofficial

Her website http://www.isabelwolff.com/

Follow her on Twitter @IsabelWolff

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

Comments (6)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- In the Media: 9th November 2014 | The Writes of Woman | November 9, 2014

I was interned on Java in Tjideng in Batavia (Djakarta now) when I was 10yrs old with my mother and younger sister.

My father and older brother were interned somewhere else, since my parents were divorced and my brother was with my father at the time. We were liberated by the Scotch Guard. I will always remember their bagpipes every morning and evening. They were fierce fighters that defended us from attacks from the local then communists that attacked us at the time. They were replaced by the British Sikhs and there was talk of rape at the time. There were also women captured by the local communists that were also raped and put in other camps and what was done to them! They were locked up another 4 yrs or so, after the Japanese camps! We were horrified what happened to them.

Our camp commander was Capt.Sonei, who became moon mad during full moons. Besides being slowly starved to death, we would have to stand for hours in the sun being counted or searched for photos we might have or jewelry and money. Some women were beaten. We were all terrorized

We could not wear sunglasses or hats, because they wanted to see our eyes, that would show fear if we hiding something. My mother was defiant and would hide other women’s items and would take their small child to hold and would look the Japs straight in the eyes and got away with hiding the items.

We slept under the overhang of the roof closed of by armoires to keep the rain out and for privacy.

Of course the wall was full of bedbugs and flees. I also remember having to dip a pan into a septic tank to empty it out in the ditch in front of the house.

I would fill up the bucket and others would empty it out in the ditch in front of the house. I don’t understand now how we did not get sick or maybe be we were! We were liberated because the Americans dropped the 2 atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yes and people in Japan don’t understand why the bombs were dropped, to liberate us on Java and other islands and also Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand and others. After a month we were evacuated to Singapore to what we now know as a refugee camp in Johore.

While we were there we heard that Capt.Sonei was hanged at the Tjangi prison in Singapore as a war criminal! Then we were evacuated to The Netherlands since polio broke out and we could not stay there. both my parents and us children were born and raised on Java. My grandparents on my father’s side were planters. Coffee, tea, rubber and quinine. I will be 88 yrs shortly and live in Florida USA, where it is warm also!!!

I share your fascination with the Pacific war–my writing has focused on Americans in the Philippines. I am very much looking forward to your novel’s U.S. release!

Dear Theresa – sorry not to have replied to your comment before, but thank you.

I’ve never heard any stories before about the Dutch men, women, and children interned in Java during WWII. Thanks for this chilling evocation. It’s so true that when we tell stories about war (any war) often the focus is on the people actually fighting, usually men. But there is a lot of suffering across the board. Your story sounds very dramatic. From your post it seems as though you decided on the setting first before the characters and their story. Is that true? How did you find/ develop your characters?

Hi Martha, thank you for your comments. The story is dual timeline, about a young ghost writer Jenni, who is commissioned to write the memoirs of an elderly Dutch woman, Klara. Klara was interned on Java, during the war, with her mother and little brother and now, as her 80th birthday approaches, has decided to tell her harrowing story at last. So yes, I’d already decided on the War in the East story as it affected those thousands of women and children. I found their storyline through the research and interviews that I did. The main planks of the story are therefore, largely about the strategies they use to survive such harsh conditions, and the relationships that they have to the other women and children – do they help them, or try to save themselves in these atrocious conditions. War brings out the best and the worst in human beings, and this was what interested me most in developing the characters. It’s also largely about Klara’s mother, and the lengths that she and all the mothers will go to, to keep their children alive. I found it such a sad area of wartime history – that those least to blame are affected so terribly. The story for Klara is to a great degree about her relationship with her little brother, Peter, and with her best friend Flora, who is also interned with her family. Anyway it comes out in the US on February 10th with the title ‘Shadows OVer Paradise’. Many thanks, Isabel