Using “real news” To Inform My Historical Mysteries

How fast can a horse travel anyway? Why was “blood-letting” used to treat epilepsy? What was the impact of the Prohibition on real people? When I started my PhD in history, I had no idea that I would one day use the skills I acquired as a researcher to answer questions like these while writing two historical mystery series (respectively set in 17th century London and 1920s Chicago).

How fast can a horse travel anyway? Why was “blood-letting” used to treat epilepsy? What was the impact of the Prohibition on real people? When I started my PhD in history, I had no idea that I would one day use the skills I acquired as a researcher to answer questions like these while writing two historical mystery series (respectively set in 17th century London and 1920s Chicago).

These questions first came to me when, early on, I was researching gender patterns of domestic homicide in 17th century—essentially, how men and women murdered differently. (And if you are curious, women tended to use instruments of the home—poison, needles, kitchen equipment, while men used tools of the trade, like awls, hammers and the like. Not overly surprising, when you think about it).

But as I read through the penny press of the time—specifically murder ballads—which were tabloid-like in that they were half-truth, half sensationalized conjecture, I came across an intriguing trend. The ballads would sing collectively of a young woman who’d been found stabbed or strangled, in a secluded glen, and in her pocket there was always a note. The note would read something like, “Dear sweetheart, meet me at midnight. Don’t tell anyone.” And it would be signed “John,” or “W”. When the community found the body (and the note) they would collectively agree on who the murderer was (since there was no established police force at the time). The man would be thrown into Newgate prison (a terrible prison with horrific conditions), eventually brought to trial, where generally he’d be found guilty and hanged.

So I always had questions—Who was this young woman? Had she known her killer? Had the man been framed? Those questions eventually became my first novel—A MURDER AT ROSAMUND’S GATE—which features a young chambermaid trying to keep her brother from being hanged for a crime he did not commit.

Historical questions would frame all of the subsequent books in the series as well. In my second book, I was intrigued by what historians of 17th century England have collectively called the “miracle” of the Great Fire of London in 1666. Despite half of London being burned down, with over 40,000 homes and businesses destroyed in 3 days, there were only 7 recorded deaths. I never understood that—could the elderly, the infirm, prisoners, all escaped? So this question serves as the backdrop of the larger story.

While I had spent a lot of time, as a doctoral student, reading about larger social, religious economic and gender trends and patterns, I realized that I had to learn a lot more about the everyday lives of people. What they ate and drank, how they paid for things, how they entertained themselves, how they got their news, and just generally, how they interacted with each other. I read through hundreds of tracts, pamphlets, ‘true accounts,’ ballads, diaries, and penny press to weave in authentic details about the everyday lives of people.

And then there were just mundane questions that required answers. There was a point, for example, that I had to figure out how long it would take a cart and two horses, carrying three people, to travel from London to Oxford (about 60 miles). I had to take into account the type of horses, the weight of a cart, the condition of the roads, the weather, and how many changing stations along the roads the travelers would encounter. I had to consult 17th century travel guides, farrier handbooks, and a range of maps to figure it out, but the pacing mattered for my story.

My historical research regularly informs my other stories as well. I was interested, for example, in better understanding how epilepsy was understood and treated in the 17th century. Bloodletting by physicians, visits to the local herbalist, someone brought in to say a few charms—all of those treatments might occur in a single setting.

However, for my new series set in 1929 Chicago, I was coming at the series from a very different perspective. Although I’ve taught American history, I never specialized in this period. Hence I thought about the research in a very different way. Since I live in the Chicago area, I walked around the streets where my new books are set. I’ve been able to watch silent films and listen to music from the period. And I’ve tried more than my fair share of Prohibition-era cocktails. And everywhere I go, I’m always meeting people who had a parent or grandparent who was a bootlegger, or a rumrunner, or cut Al Capone’s hair. The 1920s are still alive in a way that 17th century London is not.

But I was really interested in the tensions of the period—what was the impact of the Prohibition on everyday people? What was it like to work in a speakeasy? What were the tensions between the police and the community? I spent a lot of time reading the Chicago Tribune from the period, putting in interesting and authentic details from real everyday news.

Overall, though, I love the quirky and the strange, and those are the details that make my stories so fun to write.

—

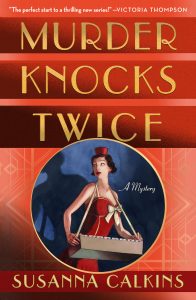

Susanna Calkins, author of the Speakeasy Murders and award-winning Lucy Campion historical series, holds a PhD in history and teaches at the college level. Her historical mysteries have been nominated for the Mary Higgins Clark and Agatha awards, among many others, and The Masque of a Murderer received a Macavity. Originally from Philadelphia, Calkins now lives in the Chicago area with her husband and two sons. Learn more at http://www.susannacalkins.com/.

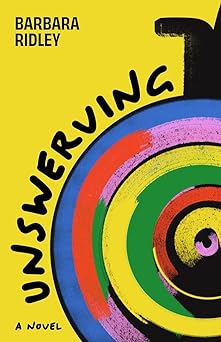

The first mystery in Susanna Calkins’ captivating new series takes readers into the dark, dangerous, and glittering underworld of a 1920s Chicago speakeasy.

The first mystery in Susanna Calkins’ captivating new series takes readers into the dark, dangerous, and glittering underworld of a 1920s Chicago speakeasy.

Gina Ricci takes on a job as a cigarette girl to earn money for her ailing father―and to prove to herself that she can hold her own at Chicago’s most notorious speakeasy, the Third Door. She’s enchanted by the harsh, glamorous world she discovers: the sleek socialites sipping bootlegged cocktails, the rowdy ex-servicemen playing poker in a curtained back room, the flirtatious jazz pianist and the brooding photographer―all overseen by the club’s imposing owner, Signora Castallazzo. But the staff buzzes with whispers about Gina’s predecessor, who died under mysterious circumstances, and the photographer, Marty, warns her to be careful.

When Marty is brutally murdered, with Gina as the only witness, she’s determined to track down his killer. What secrets did Marty capture on his camera―and who would do anything to destroy it? As Gina searches for answers, she’s pulled deeper into the shadowy truths hiding behind the Third Door.

Category: On Writing