When Readers Don’t “Get” Your Book: On The Delicate Subject of Difficult Books

When Readers Don’t “Get” Your Book: On The Delicate Subject of Difficult Books

By Lindsay Merbaum

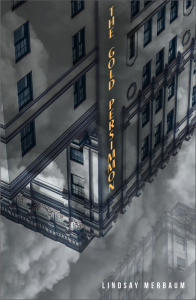

“I had to actually read every word of your book!” is a comment I’ve now heard a few times in response to my debut experimental queer feminist horror novel The Gold Persimmon, (is that enough of a mouthful for you?) Another common reaction can be summed up as “OMG! Wait, what just happened?” Likewise, “I don’t get it” appears frequently on Goodreads, a site both beloved and feared for its catalog of brutally nitpicky reviews–sometimes readers do judge a book by its cover.

“I had to actually read every word of your book!” is a comment I’ve now heard a few times in response to my debut experimental queer feminist horror novel The Gold Persimmon, (is that enough of a mouthful for you?) Another common reaction can be summed up as “OMG! Wait, what just happened?” Likewise, “I don’t get it” appears frequently on Goodreads, a site both beloved and feared for its catalog of brutally nitpicky reviews–sometimes readers do judge a book by its cover.

I’ve come to realize that for a lot of busy readers, there’s a whole lotta skimming going on: hunting and pecking for the good stuff, like picking all the chocolate out of the trail mix. Except, if The Gold Persimmon were trail mix, it would be a bunch of nuts still in the shell, which isn’t really trail mix at all.

The late, great Toni Morrison, may she rest in power, was well-known for putting the onus on readers to roll up their sleeves and do some work when reading her fiction. She told Oprah Magazine: “The words on the page are only half the story… The rest is what you bring to the party.” It’s worth noting the highly educated writers in a feminist horror class I led in February struggled to get through Morrison’s most celebrated novel, Beloved. My advice to them, which was partially helpful, was actually not to try so hard. Let the language wash over you like poetry, I suggested. Don’t try to understand every word on a literal level. Trying not to try is still work, though.

I don’t know if Morrison agreed her work was “difficult,” or how she felt about the label on a personal level. In my case, I am no Toni Morrison—how could I be? There’s only one. I am most certainly NOT a genius, either. I also don’t intend to challenge readers; it’s an effect of my writing style, which tends towards minimal exposition, mirroring, and parallel narratives. In fact, I didn’t even consider my book to be experimental until my publisher and reviewers labeled it as such. “Experimental” is a vague term that encompasses a whole swath of diverse literature. All it really means is you’re in for something different from the mainstream, a work that requires the reader to be open to a new and possibly jarring experience. The questions The Gold Persimmon leaves unanswered are part of what challenges readers and contribute to an unsettling experience. In this way, the book’s structure amplifies its effect as a work of feminist horror. Being unsettled, however, is uncomfortable and readers react to this discomfort.

The feeling of being unmoored by a book can be compounded by an author’s invisibility. When opening a novel from an unknown writer, there’s no context for it, no lengthy introduction by a recognized authority on literature, no English professor instructing the reader on how to interpret the text. Therefore, when they encounter a puzzle, they may assume the puzzle is a flaw in the book, not the result of intentionality on the author’s part. They may give up on trying to solve it. This is true of readers who’ve never studied literature just as much as it is of those with Master’s degrees in writing and English. It’s not just about what you know, it’s about how you read.

The Gold Persimmon is a maze in literal and metaphoric ways: it involves two narratives, one written by the narrator of the other, though you only learn that upon completing the book. It’s an important detail that many readers never pick up on at all, despite many hints, because it isn’t stated literally. The novel also involves an explicable fog—trapping seven people in a sex hotel, who run through pitch-black hallways, searching for each other and themselves—as well as some ghosts who at first appear to be alive. It’s like The Haunting of Hill House meets Magnolia.

Some readers have told me they felt the desire to go back to the beginning of The Gold Persimmon just as soon as they’d finished it. They wanted to look at it anew in the context of what the ending had both provided, and left a mystery. This is truly an ideal reaction from my point of view: worth reading again? Yes! I also structured the novel so that each section would shed light on what had come before, a technique which lends itself to re-reading.

Solving puzzles is why I appreciate the practice of reading a book again. And again. I’ve read Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things at least ten times: there was a period in my life where I read it once a year. I discovered it anew each time. Rereading Lolita uncovered some fantastic Easter eggs I didn’t even notice the first time around. The idea of connection you can only see in hindsight captured my imagination and certainly influenced my own work. I also took Morrison’s advice to write the book you want to read and created something strange and sad that is wholly unlike other books on the market: “I’ve never read a book like this before” is also a comment I frequently hear, and it fills me with cautious optimism every time.

Yet most readers won’t devote the time and energy to rereading, and who can blame them? There are more amazing books out there than we could ever finish in a lifetime, which leaves only a ration of attention for each book we do pick up. There’s an irony in that: we find literature challenging when it veers from the script we expect, both in form and content. While that is how innovation is achieved, many artists are not appreciated for it during their lifetimes. Instead, humans find comfort in the familiar. We watch the same movies over and over and enjoy those same narratives told in slightly different forms. The problem is, dismissing a book because it’s foreign in ways that challenge our understanding of narrative only serves to limit our knowledge, and by extension our enjoyment.

To parrot Jaime, the cheeky, self-deprecating narrator of my own novel, who’s also a burgeoning writer, perhaps the best I can hope for is to be lauded posthumously! Or perhaps future books I publish will achieve more critical and commercial success, which might enhance my rep. (Let’s be honest: how many people would’ve given Cloud Atlas a chance if it hadn’t been a critical success? I loved it, but it’s a weird book!) Taking on notoriously daunting tomes like Ulysses or House of Leaves is a badge of honor for some readers. If I’m lucky, perhaps The Gold Persimmon could achieve notoriety on a similar level. Or maybe it’ll just become notorious. Or maybe it’ll fade into the ether, where the shades of so many wonderful books reside.

In the meantime, I advocate for reading with an open heart and an open mind. Give yourself over to the text, which also means lending it your full attention. Read. Every. Word. If you can’t latch on to something, read it a few times. Mark the passage. Take notes, look up references that you don’t have knowledge around. Consider reading interviews the writer has given about the book, or essays they’ve published about their process. Consider reading the book again. Above all, trust the author and the tremendous time, energy, and intention they put into manifesting the piece of art in your hands. In the end, you still may not like it or “get” it, but you’ll certainly have gone on a journey with it, and sometimes that’s the most valuable experience.

—

Lindsay Merbaum is a queer feminist author and high priestess of home mixology. After graduating from Sarah Lawrence College, she earned her MFA in Fiction from Brooklyn College, where she was a recipient of the Himan Brown Award. Her award-nominated short fiction has appeared in PANK, Anomalous Press, The Collagist, Epiphany, Gargoyle, Day One, Harpur Palate, and Hobart, among others. Her essays and interviews can also be found in Electric Literature, Bustle, Bitch Media, The Rumpus, and more. Lindsay lives in Michigan with her partner and cats. THE GOLD PERSIMMON is her first novel.

THE GOLD PERSIMMON

Clytemnestra is a check-in girl at The Gold Persimmon, a temple-like New York City hotel with gilded furnishings and carefully guarded secrets. Cloistered in her own reality, Cly lives by a strict set of rules until a connection with a troubled hotel guest threatens the world she’s so carefully constructed.

Clytemnestra is a check-in girl at The Gold Persimmon, a temple-like New York City hotel with gilded furnishings and carefully guarded secrets. Cloistered in her own reality, Cly lives by a strict set of rules until a connection with a troubled hotel guest threatens the world she’s so carefully constructed.

In a parallel reality, an inexplicable fog envelops the city, trapping a young, nonbinary writer named Jaime in a sex hotel with six other people. As the survivors begin to turn on one another, Jaime must navigate a deadly game of cat and mouse.

Haunted by specters of grief and familial shame, Jaime and Cly find themselves trapped in dual narratives in this gripping experimental novel that explores sexuality, surveillance, and the very nature of storytelling.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips