Why Do Some Friendships End and Others Last? By Carol Dines

Why Do Some Friendships End and Others Last?

By Carol Dines

I don’t remember how it began, our daily walk. Two o’clock before the kids got off their busses. Sun, rain, snow, wind, we met at the corner midway between our houses. The lake was three miles around and took forty-five minutes. Every day we met, our dogs tugging on their leashes.

I don’t remember how it began, our daily walk. Two o’clock before the kids got off their busses. Sun, rain, snow, wind, we met at the corner midway between our houses. The lake was three miles around and took forty-five minutes. Every day we met, our dogs tugging on their leashes.

Our friendship felt effortless—need that wasn’t needy, generosity without expectation. We both felt youth had left us, oldness was just ahead. And yet when we laughed, often and breathlessly, it was the old spark, relit. We could see it was missing in our husbands, “our anchors,” we called them, burdened by responsibility and a willingness to accept the busyness of our lives without complaint. But after years of marriage, routine had entered the door and brought all its furniture. Our husbands came home from work or the gym, pouring wine, asking, “Did the electrician call you back?”

We didn’t know if we loved our lives enough, and maybe that was what bonded us. We didn’t know what we were resisting and what we were feeding in ourselves and each other. We had been other people before having children. We would be other people again. Our friendship was an opening, a way to keep our dreams alive, and our daily walks became a refuge, a place to shed worries, release truths, as if our words had been waiting for a place to land. Nothing was too sacred to talk about.

And maybe that was the problem. Maybe we shouldn’t have talked about our husbands as much as we did, conversations that shoveled deeper than our marriages. Truths revealed for the first time, the only time.

And then life happened—her husband left her, and my husband and I began counseling. Her anger toward men in general wasn’t helpful to me as I tried to see my husband through new eyes. And my commitment to working through the problems in my marriage no doubt pained her because she was grieving the loss of her own marriage. As our lives shifted, our walks, talks, and confidences felt less like a refuge and more like an expectation that left us both feeling depleted.

Although we loved and admired each other deeply, we needed a looser friendship without daily walks. But neither of us knew how to negotiate a different friendship, and instead, we found excuses not to meet which was the beginning of the end.

Now, looking back, I realize our boundaries had changed, and we didn’t know how to communicate new ones. I am not an expert on friendship, except through my own lived experience. I have had two friendships end, and I believe another one is ending now—very likely because I have grandchildren and she recently found out she will never be a grandmother, something we both longed for together. Now I try not to talk about my grandchildren when we’re together, but as they’ve become central to my life, my silence and her grief have collided, shifting the boundaries in our 50 year friendship.

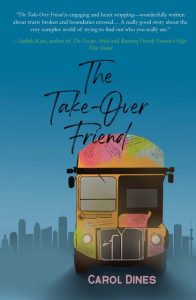

Boundaries in relationships is a subject that has long interested me and is the central theme of my two new books, This Distance We call Love, a collection of stories for adults, and my forthcoming YA novel, The Take-Over Friend. My desire to write for both audiences on this topic sprang from my own personal understanding that the boundaries (or lack of) we learn as children in our families have a great impact on the boundaries we construct as adults in our marriages, families, and friendships.

I grew up in a family that had a very tight family culture which superseded any individual boundaries I might have wanted to construct. From a very early age, family loyalty was expected, family gatherings were obligatory, and confidences remained within the family. These expectations were never spoken out loud but were celebrated, and because they were so highly valued, I never felt able to construct my own boundaries until I left home for college. The tight family culture that formed me had a lasting effect—a flight or fight response to relationships that demanded more than I felt comfortable giving.

I didn’t understand that I could decide for myself my own boundaries until I met my husband. He owned a house which I referred to as the “train station” because there was a steady stream of friends from Europe who came and stayed for weeks at a time. When friends arrived after long overseas flights, my husband stocked the fridge with wine, half and half, and ice cream. He gave them keys to the house, a map of the city, and told them to make themselves at home. He then retreated to his office at the University. His boundaries around time and space were drawn large, and no one seemed to mind. They kept returning. This was illuminating to me—clear boundaries allowed the guests to feel like they weren’t imposing, and my husband enjoyed having them stay at his house.

I’ve come to learn through him that friendship always does better with clear boundaries. And yet, it took me well into my forties to know and express my own boundaries clearly. I don’t answer the phone mornings. I don’t carry a cell with me. I dislike being a houseguest. I prefer to have my own room when traveling with friends. And I’ve had to negotiate gift-giving with two friends whose budgets were larger than my own. I’ve also been surprised that my closest friends not only support the boundaries I need to do my work and take care of myself but feel freer to share their own boundaries with me.

Covid forced all of us to examine our own boundaries in a way we never did before, giving us an excuse to define our own bubbles of choice. “We’re just not eating indoors yet.” Or, “We’re still not gathering in groups.” For many people, the friendship-plate got smaller, some friends pushed off the plate entirely, others pushed to the outer ring, and closest friends in the center where effort was made to keep the friendships alive.

But as our lives continued to adapt to a new normal, many of us began to understand that our own boundaries around time and energy and effort had shifted—we found some friendships no longer filled us but depleted us. We recognized we weren’t as honest or forthcoming as we used to be.

Some friends came out of covid needier, and they wanted more from the friendship. Other friends stopped calling altogether, never returning phonecalls or texts, asking to get together.

Since covid, I’ve had to negotiate the changes in my own friendships, asking one friend, “Are we okay? I’m been feeling like we’re not connecting like we used to.” I’ve recently had a family crisis that prevented me from seeing close friends. I’ve told them, “I’m sorry I’m not there for you right now, but I’m really being pulled in many directions, and I just don’t have the time and energy to be a good friend right now. I hope things will change soon.” My policy is: Be clear. Be honest. And if the friend isn’t receptive, give the friendship some space.

In my new YA novel, the daughter is grieving a friendship that seems on the brink of ending, and the mother tells her teenage daughter, “As you each grow separately, your friendship needs a wider container to last.” I am lucky to have four friendships that have lasted decades, but all have required wide containers to weather not only the shared joys, but also the disappointment, emotional distance, and reconnection-without-blame that comes with long friendship. Communicating our own shifting boundaries allows us to take care of ourselves, and when we do that, our friendships have the chance to last a lifetime.

—

CAROL DINES BIO:

Carol Dines writes novels and short stories for adults and young adults.

Her latest YA novel, THE TAKE-OVER FRIEND, is out now. She’s also written two additional YA novels: Best Friends Tell the Best Lies (Delacorte) and The Queen’s Soprano (Harcourt), as well as a collection of YA short stories, Talk to Me (Delacorte.)

Her latest YA novel, THE TAKE-OVER FRIEND, is out now. She’s also written two additional YA novels: Best Friends Tell the Best Lies (Delacorte) and The Queen’s Soprano (Harcourt), as well as a collection of YA short stories, Talk to Me (Delacorte.)

Her collection of short stories for adults, This Distance We Call Love, was published by Orison Books in 2021. Additionally, her fiction has appeared in numerous literary journals including Ploughshares, Narrative, Colorado Review, Salamander, Nimrod, as well as anthologies Someone Speaks My Language, Love and Lust, and Voices of the Land.

Carol Dines is a recipient of the SWCA’s Judy Blume award and the Eric Hoffer Award, as well as Minnesota and Wisconsin State Artist Fellowships. She’s a graduate of Stanford University and has an M.A. from Colorado State University. She was born in Rochester, Minnesota and currently resides in Minneapolis with her husband and standard poodle.

THE TAKE-OVER FRIEND

“A really good story about the very complex world of trying to find out who you really are.”—Judith Katz, author of The Escape Artist and Running Fiercely Toward A High Thin Sound

On the second day of ninth grade, introverted Frances meets Sonja, a wildly funny newcomer from France, and the girls form a fast friendship. Frances adores Sonja’s worldliness, and Sonja adores Frances’s family, especially her older brother, Will. Frances and Sonja immediately declare themselves “The Poets” and rally their homeroom to enter the homecoming parade with a poetry-mobile built from Frances’s father’s old band bus. But respective family crises begin to escalate, and tensions come to a head when Sonja temporarily moves in with Frances’s family—forcing each friend to decide how close is too close. Alternatingly funny and poignant, The Take-Over Friend is a smart page-turner that focuses on the importance of finding your own voice in relationships.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips