Writing About Life With Epilepsy

Like many of us, I have long thought I had a story worth sharing. As a physician with epilepsy, I felt that my own illness gave me a unique perspective on caring for those with chronic illness. As a mom and doctor with seizures, I hoped that sharing my story may help others also dealing with the chronic unknowns of epilepsy.

Like many of us, I have long thought I had a story worth sharing. As a physician with epilepsy, I felt that my own illness gave me a unique perspective on caring for those with chronic illness. As a mom and doctor with seizures, I hoped that sharing my story may help others also dealing with the chronic unknowns of epilepsy.

But until July 2009, my primary method of coping with illness was to pretend like it wasn’t there. This didn’t always work, of course, when I was blindsided with a medication side effect, temporarily crippled with an unsuspected seizure, or almost chronically worried when the next seizure would come. But my primitive desire to have my illness disappear led to silence, shame, and what eventually became a heavily guarded secret

When I was pregnant with my third child, I appeared outwardly healthy but in reality was taking escalating doses of antiepileptic medications and had taken several unplanned trips to the ER for treatment of grand mal seizures. Since my seizures occurred mostly at night, my coworkers and colleagues didn’t know what I was going through. The day before I was scheduled to deliver my daughter, I sat at my office desk, round and ready for relief. A nurse and coworker sauntered up to say goodbye and good luck before my maternity leave.

“You’ve had such an easy pregnancy,” she enthused. “Everything seems to come so easily for you.”

I smiled and nodded and wondered quietly inside how I had suffered so much without anyone other than my husband and physician knowing. Perhaps I hid my secret illness too well. Perhaps it was time to talk. Since I was too afraid to tell anyone about my epilepsy, I decided that it was time to write.

So after my perfect, healthy, daughter was born, I took advantage of the “extra” time on my maternity leave to write. I didn’t know how I was going to put my deepest fears and greatest vulnerabilities into words, but I knew that it was time to step out of the shadows. In my years of training to be a physician, I learned without doubt that illness is an unacceptable unknown for doctors. We were supposed to heal the ill but ward off our own illness with inexplicable forces.

But with my newborn daughter wrapped in a sling around my waist, I knew it was time to challenge these untruths. With the familiar keyboard glowing warm under my fingertips, I started at the beginning and worked chronologically through years of testing, procedures, hardship, and some pain. I wrote about the joy of graduating from medical school, helping downcast patients, and becoming a mother. I poured my thoughts, anxiety, worries, and fears into my laptop. When it was time to go back to work 12 weeks later, I found that each page was a little easier to write, each weakness a bit easier to disclose, and every fear a little less grave as I revealed it to the faceless but understanding computer.

70,000 words later, I typed the (first) last word of my memoir. When I pressed SAVE and closed the top of my laptop, I noticed that my spirit was a little lighter. What started out as a project to help and enlighten others turned out to be an exercise to comfort my soul. The previous fear of the unknown that gripped me was melting like the Wicked Witch in a rainstorm. By writing and uncovering my vulnerabilities, I was no longer perpetually vulnerable.

I found that writing my truth without censoring for fear of exposure, judgment, or criticism was the best way that I could learn to live with my illness. My unharnessed words on the electronic page sometimes revealed a deeper truth than my spoken thoughts could reveal.

The following passage is near the end of my book. When I reached this point, I was almost able to write without thinking, connecting to the deepest parts of my heart, writing my truth more purely than ever before. Writing my memoir was difficult, but it taught me to cope. And in that way, it set me free.

In the twenty years since I was diagnosed with epilepsy, my disease took many shapes. In turn, I’ve carried many labels. Complex partial. Surgically correctable. Recurrent. Intractable.

I wasn’t curable, but I was still teachable. I stepped down from my vantage point over Madison and rested in the knowledge that I was still walking on this infinite journey.

Perhaps there’s beauty in the way epilepsy taught me grace, gratitude, perseverance, strength, and hope. Maybe I needed to take this journey to become mindful of the blessings surrounding me. Perhaps only when forced to live with vulnerability and uncertainty could I learn to treasure and give thanks for the simplest of things. Maybe I learned to care for all aspects of each patient only after I was a patient myself. I resolved to live a purposeful life shaped by these truths.

I was at peace with epilepsy, peace moving in like the quiet after a storm. The fingers of acceptance and understanding tickled my strong will and it was no longer necessary to live in a shadow. Dual lives are for those who’re ashamed. Concealed vulnerabilities are for those who’re unwilling to accept that they’re always vulnerable. It was time for me to lift the curtain and claim the irreparably damaged parts of me.

I was no longer ashamed.

—

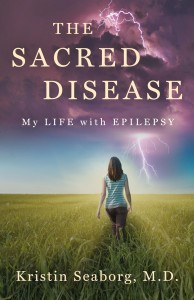

Kristin Seaborg is a practicing pediatrician in Madison, Wisconsin, where she lives with her husband and three children. She contributes magazine articles about pediatrics and parenting, and writes a blog about epilepsy, www.oneintwentysix.com.

An advocate for epilepsy awareness, Kristin hopes that writing about her disease will help decrease the stigma associated with seizures. You can find Kristin at www.kristinseaborg.com, on Facebook at Kristin Seaborg MD, Author, and on Twitter @KristinSeaborg.

You can buy her memoir HERE

Category: On Writing

I’m just going to check and see if this is available in Australia, I shared this on FB and she is desperate to get hold of it.

looks like this is a book that needed to be written