Writing Past the “Happily Ever After”

There’s an image I remember from a movie I watched as a child, of a princess looking across the sea at a castle on a mountain, her soon-to-be home with the prince of her dreams. With that scene, the movie ended, but my contemplating had just begun. What happens now, I wondered. How do the days of love unfold?

There’s an image I remember from a movie I watched as a child, of a princess looking across the sea at a castle on a mountain, her soon-to-be home with the prince of her dreams. With that scene, the movie ended, but my contemplating had just begun. What happens now, I wondered. How do the days of love unfold?

Fairy tales today consist primarily of the “happily ever after” variety. But they are often based on much older stories where the realities of pain and disillusionment aren’t filtered. Hans Christian Anderson’s little mermaid, for instance, feels the stab of a knife with every step she takes on her new legs. In the end, her prince marries another woman, and the little mermaid turns into sea foam. I could understand why the Disney version is preferable. People want reassurance that love can surpass tribulations, that life, and people, are ultimately good, and that their good deeds will be rewarded.

But what is lost in these happily ever afters? When we know that a happily ever after is coming, we experience the whole story expecting every loose end to be resolved to the protagonists’ benefit. The reward is seeing what we hope for and feel comforted by come to fruition, but I believe there are more interesting things to gain from stories than comfort. Like feeling dared by the unexpected, uncomfortable enough to question, surprised at what’s possible, and challenged to try on new ideas. Some stories are designed to put you to sleep; I prefer the ones that keep me awake for days.

Modern-day fairy tales seem to have lost their dark edges and complexity. But this doesn’t mean you can’t continue the discussions they warrant. I often have conversations with my daughters about what angles may have been left unfollowed or possibilities unmentioned, what realities ignored or alternatives bypassed. “Why was it so important for her to marry the prince? Did she have any other choices?” By interacting with stories in this way, they are not just something we are entertained by, but something we have a stake in.

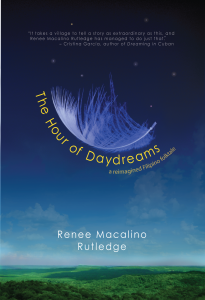

This type of interaction became the entryway for my first novel, The Hour of Daydreams. Years ago, when I read a collection of Filipino folktales, Tales from the 7,000 Isles, one particular retelling stood out to me. In it, a man falls in love with seven maidens who fly to a river each night. He steals a pair of wings, and the maiden who cannot fly away ends up marrying him.

Different from fairy tales, folktales are stories that have been told orally for generations as a form of entertainment and eventually written down. Their written forms attempt to stay true to the original, retaining the stories’ cultural DNA and historical significance. Some have good endings, some bad, often to teach a lesson or reflect the culture’s values.

A romantic at heart, I was drawn to the imagery of the night and the stars in the star maiden story. The wings called out to me like talismans. But the love story required dismantling. Did the one who had her wings stolen love the man who tricked her? Did the man who stole love the one he’d stolen from? What was their marriage like, given the circumstances that brought them together? Writing The Hour of Daydreams was my attempt to interact with the folktale and tackle the questions it brought to the surface.

In the process, I came to write a book about marriage and myths, the ones we tell ourselves, and the ones we tell each other. From the moment the reader encounters the female protagonist, Tala, they understand she is anything but passive and in the midst of a daily routine that the male protagonist, Manolo, has no idea about.

In the process, I came to write a book about marriage and myths, the ones we tell ourselves, and the ones we tell each other. From the moment the reader encounters the female protagonist, Tala, they understand she is anything but passive and in the midst of a daily routine that the male protagonist, Manolo, has no idea about.

For the duration of the novel, Tala can be seen as controlling the direction of the story, with Manolo trying his best to keep up, turning the patriarchal theme of male domination and control in the folktale version on its head. The novel becomes an interpretation of the folktale’s origin, offering a theory of how a folktale might begin with a life event that is shared, changing a little with each retelling until it finds a familiar shape that ultimately gets passed down.

If folktales help us to understand a culture, then there’s an even greater stake to not only preserve them, but question them and remember that every person will see the story differently, and each generation that inherits the tales will be different from the last. There are few constants in life—even, or perhaps, especially, in marriage.

The folktale’s ending isn’t a happily ever after, but one in which there’s a lesson to be told. The maiden eventually finds her wings and uses them to fly away, but even this is predictable: do wrong and you will be punished. Each time I worked toward this ending, the novel felt forced. Finally, I decided to ignore it altogether. This worked. What resulted is a series of beginnings.

Happiness is a good end to strive for, but growth comes from its absence and return. It means the happiness is real, because it’s the kind that’s sustainable and not fabricated. There are dips and detours. There is the steady and sure, and the unknown. One’s motives often do not match one’s actions. And the result can be devastating or affirming, uneventful or lasting. Life is about all of it, and stories should be too.

—

Category: On Writing