Becoming a Writer: Calibrating the Work Against the Pleasure

I met Jacomena van Huizen Maybeck when I was thirty-three and she was seventy-seven. I’d hoped to rent her cottage, and found her tarring the roof, dressed in a halter top and shorts. I’d never met anyone like her. She knew how to throw a pot, wield an ax or a sickle, and make plum jam. She took relationships seriously and had many longstanding friends.

I met Jacomena van Huizen Maybeck when I was thirty-three and she was seventy-seven. I’d hoped to rent her cottage, and found her tarring the roof, dressed in a halter top and shorts. I’d never met anyone like her. She knew how to throw a pot, wield an ax or a sickle, and make plum jam. She took relationships seriously and had many longstanding friends.

She introduced me to her friends, mostly women educated during the 1920s and now thriving in their winter years. I was a photographer at the time, making a living as a dental hygienist. I was intrigued with these older women and began doing formal portraits of them. Because we’re used to seeing ourselves in movement, the women were surprised but proud to see their wrinkles in stark black and white.

After entering a few shows and competitions, the photo collection went into the closet. I became obsessed with this problem—what do you do with your completed work? Jacomena suggested making a book and offered to come along with me on many interviews. While talking with the women, a different view of aging and what was possible began to coalesce.

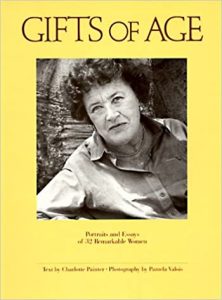

After another year or so, the book was finally ready for my agent to present to publishers. In summary, they loved the idea and praised the photos but felt that my writing was weak. I still have all the rejection letters! A local writer gently suggested that I team up with a seasoned writer, Charlotte Painter, and together we re-interviewed the women. Charlotte’s short portrayals were elegant; Chronicle Books offered us a contract. Gifts of Age: Portraits and Essays of 32 Remarkable Women sold over 125,000 copies.

Jacomena continued her long and creative life into her mid-nineties. She’d become a well-known ceramicist and declared that a privilege of old age was that she could make things just for herself—she no longer felt obliged to compete and make things that would look good in an exhibition. “These days, I calibrate the work against the pleasure. When you’re doing it for yourself, you make the greatest picture or pot.” We were close friends and she helped me through my child-rearing years, always encouraging me to continue with photography.

Jacomena continued her long and creative life into her mid-nineties. She’d become a well-known ceramicist and declared that a privilege of old age was that she could make things just for herself—she no longer felt obliged to compete and make things that would look good in an exhibition. “These days, I calibrate the work against the pleasure. When you’re doing it for yourself, you make the greatest picture or pot.” We were close friends and she helped me through my child-rearing years, always encouraging me to continue with photography.

Eight years ago, my husband and I bought Jacomena’s home. I realized that I knew little about her early life—what had shaped and supported her in preparation for her later years? I began the research and interviews that would keep me busy as I moved into my own winter years. Jacomena’s grandchildren searched drawers and closets and found invaluable diaries and photos which excited me.

I learned who she was in her thirties and forties, and how those experiences created her self-confidence and flexibility as she reared twins while longing for “creative work.” Jacomena married her childhood sweetheart who left her a widow at age sixty-one. Her approach to life in her winter years inspire me now in my current season.

But would I dare write again, after my experience with Gifts of Age? I took several memoir writing classes, studied Charlotte’s and others’ writing styles, and began to write Jacomena’s story. Finally satisfied with the first draft, I asked a writer friend to read it and she advised me to “put more of myself into it.” I was disappointed with her comments, and unsure that I could make more changes.

I was then in my mid-seventies, forgetting old friends’ names, and misplacing my car keys. Could I re-write this story? And then what—would it too sit in a closet? Why was I writing it, and who will read it? I thought of Jacomena’s words—perhaps I’ll just do it for myself and for the pleasure of honoring her life.

For many of us, the beauty of being in our winter years is that we do not have to rush through our days. I often think about how Jacomena organized her days. She kept a daily journal throughout her seventies and eighties which helped me understand her challenges. She was adamant about doing “outside work” daily—clearing brush, trimming trees, or making a railing out of branches for her “wobbly friends.”

She’d married into a famous family and became the spokeswoman for her architect father-in-law, Bernard Maybeck, writing a story about the family when she was seventy-nine. At age ninety-one, she published her own memoirs. Perhaps buoyed by Jacomena’s courage in writing, I re-wrote my story and promised friends that I was “on my last draft!” A friend sent me John McPhee’s essay, “Draft No. 4” which immediately stopped my whining. I found that I enjoyed editing even more than writing. I can remember the early 1980s when Charlotte discovered “cutting and pasting” on the computer and tried to explain it to me. Two editors read and helped shape my story until I really did have a last version.

Having a serious project to look forward to every day, has brought me great joy. Some days it was like solving a puzzle – finding the right piece for the space. Other days were spent reviewing the paperwork I’d amassed from interviews, libraries, and other books, looking for inspiration. It was the perfect project for me in my seventies, giving me a sense of purpose I’d not had since retirement.

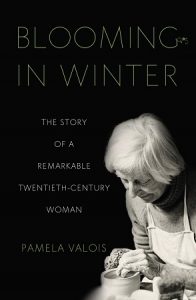

I’ll be sad as well as relieved to complete this project. I’ll look out the same windows that Jacomena looked out long ago, admiring the petunias I’ve planted for the summer. The flowering trees have lost their blossoms and shades of green surround the house. Perhaps I’ll read Blooming in Winter again, this time looking for inspiration from Jacomena about how she managed to live a zestful life to the end. —

—

PAMELA VALOIS: Growing up in Sierra Madre, CA, Pamela Valois moved north to attend UC Berkeley during the Free Speech Movement. After almost flunking out due to political rallies, she returned to Los Angeles to become a dental hygienist. Then, with a solid part-time job, she became a quasi-hippie, selling macramé and her photos at weekend craft fairs. Pam got married on the lawn of Jacomena Maybeck’s Berkeley cottage and studied photography with Ruth Bernhard in San Francisco.

Her book “Gifts of Age: Portraits and Essays of 32 Remarkable Women,” a bestseller inspired by Jacomena, was published in 1985. After mothering two sons, Pam earned a master’s degree and started a new career in health care. Now at age seventy-five, she’s been retired for ten years.

She lives in Jacomena’s “High House” with her husband—it’s like a tree house, with redwoods, deer, and skunks as neighbors. For more information, please visit: https://

BLOOMING IN WINTER

When Pam Valois met her in the 1970s, Jacomena (Jackie) Maybeck was a model of zestful, hands-on living and aging, still tarring roofs and splitting logs in her seventies, and Pam was a young working mother trying to carve out time for creative projects. Jackie became her mentor, and their friendship led to a best-selling book, Gifts of Age, that features portraits of Jackie and other exemplary women in the winter of their lives.

When Pam Valois met her in the 1970s, Jacomena (Jackie) Maybeck was a model of zestful, hands-on living and aging, still tarring roofs and splitting logs in her seventies, and Pam was a young working mother trying to carve out time for creative projects. Jackie became her mentor, and their friendship led to a best-selling book, Gifts of Age, that features portraits of Jackie and other exemplary women in the winter of their lives.

Decades later, when Pam and her husband bought Jackie’s home, she realized that she knew little about her mentor’s fascinating life. What had shaped and supported Jackie in living “at full tilt” until her death at ninety-five? Blooming in Winter tells this tale―a story that stretches from Java to a magical house designed by Jackie’s famous father-in-law, Bernard Maybeck, chronicling her early years as an immigrant and ranch girl and later as a bohemian, mother of twins, ceramicist, and widow, and, ultimately, the steward of the Maybeck legacy. Along the way, Jackie became an old woman who lived with grace and aplomb.

Her uncommon approach to life encourages us to reflect on our own lives and what it looks like to live exuberantly to the very end.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Thank you so much for publishing my story on my actual pub. date! I can’t think of a more wonderful and supportive way to begin the celebration!