How Courageous Are You?

Since publishing my own story a year ago, and gathering the stories of women who wished to share their truths in a collaborative anthology, I have been reminded just how difficult it can be to put our truths out into the world.

Since publishing my own story a year ago, and gathering the stories of women who wished to share their truths in a collaborative anthology, I have been reminded just how difficult it can be to put our truths out into the world.

Sharing our stories makes us vulnerable to criticism and judgment. Yet our life lessons serve as a catalyst for other women who desire to tell their own truths.

Women have been sharing their stories for centuries. While they haven’t always been included in the literary canon, they have found the courage to speak their truths—even when they have not been heard.

Mary Wollstonecraft had the courage to put pen to paper in 18th century England, clearly articulating the reasons women should be offered the same opportunities as men, including full access to education, the right to earn and keep their own wages, and the ability to participate in the political system that governed them. Through her public declaration, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, she spoke not only her truth, but the truth of countless others who were suffering in silence.

Nearly a century later and an ocean away, Elizabeth Cady Stanton discovered that she had the strength to continue that public debate. As a young wife and mother in the small New York town of Seneca Falls, she stood before a curious crowd of men and women and delivered her first speech, A Declaration of Sentiments, demanding that women be given all of the rights due them as citizens of the United States—including the right to vote.

Fifty years later as an old woman nearing the end of her life—a woman who still could not participate in the elective franchise—Elizabeth stood again, this time in front of the state legislature. In The Solitude of Self, she spoke eloquently of the need for all human beings to chart their own course; no matter how much we may desire to be supported by others, along our journey we face many of life’s greatest challenges, including grief and death, alone. It is essential that we be equally prepared to navigate our way.

Fifty years later as an old woman nearing the end of her life—a woman who still could not participate in the elective franchise—Elizabeth stood again, this time in front of the state legislature. In The Solitude of Self, she spoke eloquently of the need for all human beings to chart their own course; no matter how much we may desire to be supported by others, along our journey we face many of life’s greatest challenges, including grief and death, alone. It is essential that we be equally prepared to navigate our way.

Kate Chopin and Zora Neale Hurston wrote their truths in fiction. Through their groundbreaking works The Awakening and Their Eyes Were Watching God, they painstakingly detailed women’s truths—the desperate tragedy of a self lost, and the triumph of a self reclaimed.

Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton chose confessional poetry as the vehicle through which to tell their truths—the pain of grief, depression, and mental illness, the torment of addiction.

Adrienne Rich and Nancy Mairs, in Of Woman Born and Plaintext, used nonfiction to detail their struggles with traditional marriage and motherhood. Walking that narrowly defined path to socially constructed happiness nearly destroyed both women, who found their way out of the darkness only after stepping off that path and actively choosing a more genuine one.

Maya Angelou spoke her truth through both nonfiction and poetry; in her first autobiographical work, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, she shared the harrowing experience of sexual assault through the eyes of a seven-year-old child. And then she wrote of women’s glory and beauty—her own glory and beauty and reclamation of self—in her poem “Phenomenal Woman.”

Women today continue to share their painful life lessons. Sue Monk Kidd describes her own spiritual crisis and reawakening to the sacred feminine in The Dance of the Dissident Daughter. In Paula, Isabel Allende describes the horrific pain of losing a child and the overwhelming realization that all that exists in the universe is at once nothing and everything, all immortal and interconnected. Each and every day women are rising to tell their truths and bare their souls.

Women’s stories are vital; they help us to heal ourselves and transform the world in which we live. We need to support one another as we find our voices and share our truths. I owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to all of the women who had the courage to share their truths before me; I hope that by sharing my own story as well as the stories of others, I am helping the women who surround me now, and providing vital life lessons for the girls who will be women tomorrow.

Do you see yourself following in the footsteps of or carrying forward the work of any of these writers or another woman writer? Do you see your work fitting within the ongoing history of women writers?

Do you have a truth you are compelled to share but are resisting making yourself vulnerable by sharing it publicly?

Or have you shared your own truths, only to be met with criticism, resistance, or silence? What’s your experience?

—

Editor’s Note: If you also share what’s worked for you we may be able to compile a piece and include some of your responses. – AMc

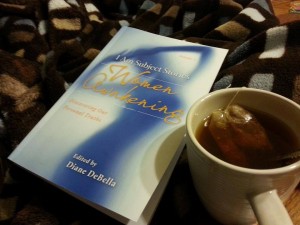

Diane DeBella is an author, and educator on feminism, women writers and women’s history based in Colorado (USA). In 2013 she completed an extensive and unique collective biography I Am Subject: Sharing Our Truths that surveyed very important women writers of the past two centuries woven within her own memoir. In 2014 she initiated an I Am Subject anthology: Women Awakening, which she announced while she was a WWWB Site Sponsor. Visit her website I Am Subject.com, connect with Diane DeBella on Facebook, and follow her on Twitter @DianeDeBella.

Diane is so knowledgeable about women writers’ lives, writing and feminism that following what she posts is very interesting. – AMc

Category: By Current and Past Sponsors, On Writing, US American Women Writers, Women Writing Memoirs, Women Writing Non-Fiction

Comments (12)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post

- 7 Ways to Embrace Your Vulnerability and Write Your Truth | March 12, 2015

Diane,

All those women to whom you refer, who bravely spoke their truth, had hard times as well. If you read about their personal lives, you find that the truth sometimes hurts, and the storyteller, the messenger, often is blamed. Some of these women were ridiculed, suffered from severe depression, even ended their own life. So, if we decide that we want to tell our story and take care of our self, then we might do so. There is no obligation. For the victim of rape, incest, assault, telling one person may be all. And waiting to tell our story, until we have healed somewhat, is essential. Thanks for sharing!

Mary Ellen,

You are absolutely right! I explore all of these women’s lives, and many more women as well, in my book I Am Subject: Sharing Our Truths to Reclaim Our Selves. I include them precisely because they all encountered tremendous obstacles in their lives. I agree that each woman and each story is unique. What is most important is that women who have experienced trauma have the opportunity to heal. Perhaps that means journaling about your experiences just for yourself. Maybe it means sharing your experiences with one close friend. Or it could mean reaching a point where you have the desire to share your truths with a larger audience. You are correct to point out that the healing process for everyone is unique. Thank you so much for taking the time to read!

With gratitude,

Diane

I wrote about some of the unforeseen quirks of life in being a young woman coming of age after the Sexual Revolution but just before the AIDS crisis hit. I did get an MFA with the novel.

But my questions, though gently depicted and with a bit of whimsy, alienated a mentor of mine and one of my committee members. The one prof in my corner died. A very famous writer with whom I’d connected on my prior job wanted to read my novel. But when her assistant found out what was in the plot, she would not put the ms in the author’s “to do” pile. Repeatedly. The author became even more famous, and thereby impossible for me to approach on her own.

I had already been forced to lose our savings on one year at an Ivy League school MFA program. The tuition was lost when I was warned at the end of the year, “They’ll never let you graduate with that thesis.” I had to transfer. (At least I finished the MFA elsewhere.)

After all that, I was getting gun shy. I had no one knowledgable left to look at it, no one, that is, who I didn’t have to worry about harming my career. I had young readers of various backgrounds who’d read the manuscript and say, “I wish we had things like this to read out there.”

Finally, at the point of beginning to write a follow up novel, I delved so much into the research, I completed a PhD.

I published a well-received (though little known) study on how some women writers have evaded censorship. The book won an award in feminist studies. The people who gave it to me had no idea that the idea for the study began with my own life.

Teaching awards, national papers, more publishing. No tenure track jobs, no work.

Maybe it’s time to revisit my first love, fiction writing. Maybe I’ll see it through this time.

Do you think the reading world will still be quite as actively censoring toward the coming of age story of a middle-of-the-road liberal girl who was supposed to have been aborted? A girl who chooses to *not* have sex before she settles down?

Or are my and my main character’s personal choices, no matter how respectfully conveyed, still “moot issues,” as my once-mentor called them? How can “personal choice” in an era of “personal choice” seem so threatening, even when I made my main character a lovable screw-up? (That was what workshop readers thought of her before they’d find out that her choices conflicted, goofily, politely, with theirs and those of other characters).

Why would one little weirdo be such a problem?

Emmy,

If an issue is an issue for you, it is not “moot.” It always saddens me to hear experiences such as yours, where women are not supportive of one another. Horizontal hostility keeps us from finding solidarity and true sisterhood (bell hooks). And while we are not all equally oppressed or privileged, we should encourage each other to share our truths. Telling our stories (whether through nonfiction, fiction, poetry, etc.) heals ourselves and helps others who may be suffering in silence and isolation. As to your question about fiction, I believe we desperately need more coming of age stories for young women–so I say go for it! And how can one woman cause so much fear? When we speak our truths, it makes others uncomfortable. Yet it is by sitting with that discomfort that we stretch and grow. That can be frightening for people who have been taught that we shouldn’t share those personal parts of ourselves. Keep sharing, Emmy. You are making a difference.

With gratitude,

Diane

Hi Emmy, I was wondering if I could contact you about an article I’m writing about the risks women face when they disclose personal stories via writing (either memoirs or personal essays). I’m specifically interested in disclosures related to either sex or addiction, or other things that are less permissible, especially for women. Writing a memoir about a family member dying or other struggles won’t attract the criticism women can encounter for sharing stuff like what you mentioned. Would you be able to contact me via the blog I linked to? (Just click on my name) Or my Twitter account, I’m @parallax_angle.

Anyone else reading this who has published about these “risky” topics — whether you encountered criticism or not — I’d love to hear from you too.

Courage can be defined in so many ways. I think you ask a brilliant question. I do have something I’m dying to share – actually it’s already written but I fear my ability to weather naysayers and critics. Your post has made me think about my reluctance to put it out there in a finished form. My motto this year is to recognize a reluctance, a fear, a phobia and then attack it full frontal. Thank you for an important look back and a nudge forward.

Suzanne,

Your fear is understandable. I was discussing this very point with my students today. While I know putting our truths out there for all to see (and judge) is not possible for every woman, I am grateful to those who have shared their stories, for their experiences have helped me to understand my own. I hope you will share your truth – if and when it feels right to do so – as I am sure that your truth will not only help you to heal, but it will also help others. Yet even if women do not feel they can publicly share their stories, it is important that they can sit with their own truths, and be kind and gentle with themselves as they heal and move forward.

Great post, Diane. I’ve actually just published my memoir On Hearing of My Mother’s Death Six Years After It Happened, which features the essay I wrote for your #iamsubject project. The essay was about writing the memoir and how it forced me to reconnect my current self with the young woman I once was, which was a very accurate depiction of how I felt about the process. It was disturbing, uncomfortable, and in many ways unpleasant – yet for some reason I was never afraid. Perhaps I was naive, but I never feared public reaction. I never worried about being ridiculed, judged or criticized because of what I’d written – any more than any writer does when releasing new work into the world.

Well, here’s what’s funny. I still don’t feel that way – although that could change when reviews start coming in! – but in the process I have become painfully aware that many other people – particularly women – do. Several times a day someone on social media congratulates me on my courage in sharing my story. To a certain extent, I understand it, because it is very personal, and I’ve definitely exposed a tremendously painful part of my past without much regard for protecting my privacy. But am I brave? Why should I have to be? Why should I have to be brave in order to tell my story? I was not mentally ill; my mother was. I did not become psychotic and violent; that was my mother. We were victims, both of us, victims of a disease that took control of both of our lives. Courage shouldn’t have to enter into the equation.

Every day since I began promoting my book, people have approached me online, hinting at stories of their own that they might like to tell, about mental illness, about child abuse, about dysfunctional family relationships. They aren’t quite courageous enough to share their pain – but they’re coming closer. Seeing a story like yours or like mine makes them think that perhaps they could indeed share it – that there might be those sitting in silence who might like to read it.

I still don’t think it’s right that guiltless victims should feel ashamed to admit what’s happened to them. I don’t think courage ought to be a requirement for telling a truth. But they do, and it is. And while I may one day understand why I ought to have feared criticism and judgment when I published my memoir, I will always be proud to know that for every judge, for every critic, there are others for whom my story will help to break down the barrier between speaking and silence.

Lori,

Congratulations on the publication of your memoir! I was so thrilled to include your piece in I Am Subject Stories: Women Awakening. I agree with you. I didn’t feel particularly courageous when I put my truths out into the world. Yet those who have read my memoir tell me how brave they think it was that I put my story out into the world. I believe the women who came before me and shared their truths–the truths that helped me better understand myself–were courageous. Perhaps when we are ready to tell our stories–when we need to heal ourselves and we also want our truths to help others–we simply need to release what we have been holding inside out into the world, and we no longer fear the repercussions. We just know it is time.

Courage. Who would ever think that writing would take courage? Combat? Yes. Police work? Yes. Protests? Yes. But writing?

That’s what I thought way back when. Courage to write? Clearly I hadn’t started trying to write anything for the public. Clearly I hadn’t started to dig below the surface into the realms that others may disagree with, deny, criticize and even condemn.

I haven’t liked learning that courage isn’t something I can just jump into or onto. I have to learn to work with the fear. Practice tolerating it. Relaxing. Trying again. Building an almost cellular stamina for fear, until I demonstrate to my whole being – my instinctive nervous system – that this stating of my truth (be it in fiction or non-fiction, both) is bearable, and won’t get me killed.

For women in some parts of the world, the risk is way higher – the risk is of possible death. Look at Malala who got shot in the head for going to school. That’s a whole other level.

But in countries like America, Canada, Australia, members of the European Union, most of us don’t actually risk physical harm for telling our truths, yet still, tolerating the potential, and actual, lack of support or outright disregard and disrespect, takes practice, skill-building, and determination – if we didn’t come by it naturally.

You have amazing courage to have written your disclosing memoir, sharing truths that are, as many women’s truths have been, often whispered, not able to be spoken in full voice, in public.

Dare we talk of rape, incest, anorexia, bulemia, cutting, promiscuity, infidelity, violence against us, depression, addictions… yet if we don’t speak up, how will others learn, understand, benefit from our experience.

You educate those of us who haven’t learned about women’s history, and women writers through the past couple of centuries both in your memoir and this essay. And you show the importance of each of our stories through your anthology, Women Awakening.

I always enjoy reading your summaries about women writers’ contributions through time. Summaries help me determine whether I need to read their work next, or soon. – –

Thank you Diane! — Anora McGaha, Founding Editor, WWWB

Anora,

You bring up such an important point when you state that in many places women cannot speak their truths without fearing for their safety. We must be mindful of issues related to privilege and oppression. We are not all equally oppressed (bell hooks). Yesterday a former student of mine, a Muslim woman from Kuwait, sent me the link to this song by a woman from Saudi Arabia – it is titled Gender Game. It makes such a powerful point. Can we risk revealing ourselves?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j0XfwgbrWmo&feature=youtu.be

With gratitude,

Diane