Interview with Ann Hazzard

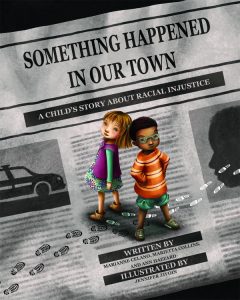

Ann Hazzard, Ph.D. is a retired clinical psychologist who worked mostly with children and families. Along with two colleagues, Marietta Collins, Ph.D. and Marianne Celano, Ph.D., she recently published her first book, Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice (Magination Press, 2018). The book follows two families – one White, one Black – as they discuss a police shooting of an unarmed Black man in their community.

Ann Hazzard, Ph.D. is a retired clinical psychologist who worked mostly with children and families. Along with two colleagues, Marietta Collins, Ph.D. and Marianne Celano, Ph.D., she recently published her first book, Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice (Magination Press, 2018). The book follows two families – one White, one Black – as they discuss a police shooting of an unarmed Black man in their community.

The story aims to answer children’s questions about such traumatic events, and to help children identify and counter racial injustice in their own lives. The three authors worked together for over two decades at Emory University in Atlanta, GA. Dr. Collins is now on the faculty at Morehouse University.

1. SOMETHING HAPPENED IN OUR TOWN: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice helps adults talk to children about race and racial injustice. What are the challenges in writing about these sensitive issues?

We had to balance staying true to our core beliefs with keeping the book accessible and appealing to as wide a range of families as possible. We believe that racism continues to be a major problem in America and we didn’t pull any punches in presenting the Black family in the story as distrustful and angry about police treatment of African-Americans. At the same time, we wanted this book to be helpful to parents of diverse ethnicities. Most Black parents already talk to their children about racial injustice in order to prepare and protect them. In contrast, most White parents avoid talking about race with their children. We hoped our book would be a helpful resource that would enable these parents to have family conversations that directly address racial injustice. Thus, a major challenge was to write a book that acknowledged the reality of racism yet would engender empathy and corrective action rather than defensiveness among most White parents.

2. How can we use stories to help start difficult conversations?

Stories help us process difficult events while creating a sense of distance that makes those events feel less overwhelming. Our story introduces children to racism as a White family discusses the history of slavery and subsequent segregation in housing and schooling. Then, members of a Black family express concerns about biased treatment of Black individuals by police in modern-day America. Both families also mention incidents of everyday racism such as teasing or exclusion.

Our picture book is designed to be read by parents to children (ages 4 to 8) and to be used as a springboard for discussion. Parents can first elicit children’s feelings by asking about past events and then moving to current events. Parents can also begin by asking children to imagine the feelings of story characters, which is less threatening, and then inviting children to share personal stories of experiencing or witnessing bias.

After children are introduced to the topic of racial injustice, which often elicits feelings of sadness and anger, we offer clear messages of hope. In the final portion of the story, the main characters Emma and Josh are successful in helping an excluded peer. Thus, child readers can experience a sense of mastery and empowerment to effect positive change.

3. As a clinical psychologist you work with diverse children and families. How has this impacted the scope of your writing?

As a psychologist, I was used to talking to young children and parents. Those experiences helped me translate complex ideas into words which were developmentally appropriate and understandable. For example, to discuss racial injustice, we used language such as “not being treated fairly”, to which children could easily relate.

Another experience as a child therapist which influenced my work as an author was my use of therapeutic storytelling. In this intervention, the therapist composes a story in which a child client’s psychological problem is metaphorically represented. As the story evolves, therapeutic messages are presented which help the child gain a new perspective or adapt healthier coping strategies. My co-author Marianne Celano and I have informally written dozens of these stories over the years, which helped us tap into our creativity to develop inspiration for this book.

4. What kind of research did you do for this book?

My two co-authors have done lots of training on cross-cultural competence for behavioral health providers. Thus, they were already very familiar with the psychological literature on racial identity development and implicit bias. We also examined the research on the origins of prejudice in children and racial socialization processes in families. Early childhood educators have been leaders in trying to reduce bias in classroom settings, and that work was helpful in developing the appendix for parents that provides guidance for discussing racial injustice. Finally, organizational and social psychologists have documented that diversity adds value. We communicated this finding in our messaging to parents that diversity should be celebrated, not just tolerated or accepted. In the story text, one of the characters expresses this sentiment by saying, “You never know who’s going to be your best friend.”

5. What are some guidelines for portraying inclusive, diverse characters in stories?

As authors, we spent quite a bit of time discussing the range of characters we would include. While the two main story characters are a White girl and a Black boy, characters of other ethnicities are present. For all characters, we thought carefully about names, activities, and emotional reactions. We tried to be realistic and representative in our dialogue. For example, we chose to have the African-American father in our story express fairly intense anger about the police shooting. However, we recognize that there are many ways for parents of different races to respond appropriately to questions about police violence.

Given that this was a picture book, active collaboration with the illustrator, Jennifer Zivoin, was another opportunity for positive portrayals of diverse characters. She created characters of diverse size and appearance to convey an acceptance of differences across many dimensions. We wanted to make sure that the African-American characters looked realistic and not like brown versions of White characters. She utilized diverse skin tones, hairstyles, and subtle facial features to create a vibrant African-American family.

6. How can you prepare yourself for criticism when you write about controversial topics?

As we were writing the book, we struggled with how best to present the police shooting incident. We took the position that the shooting was clearly unwarranted because the victim was unarmed. From the Black family’s perspective, the incident is viewed as related to police bias against African-Americans. This presentation seemed essential in order to capture the distrust that most African-Americans currently voice related to police activities and shootings.

On the other hand, we recognize that police officers have a difficult and important job of protecting the public and upholding the law, and that it is appropriate for children to view police officers as generally helpful. We tried to provide balance in the families’ discussions of the police. For example, the African-American father says “There are many cops, black and white, who make good choices”.

Of course, the reality is that you can’t fully road-test reactions to your story until it’s published. We have been pleased that the children with whom we have read the book seem to maintain a generally positive view of police, but are aware that police officers may make mistakes.

Nevertheless, we weren’t really prepared for our book to become the centerpiece of an online debate in a national publication between those who share our concerns about racially disproportionate police violence and those who view the police as unfairly criticized and blame Black victims. In retrospect, we shouldn’t have been surprised. Our book was born out of our concerns about the divisiveness in our country, which has strong racial overtones. As such, it was probably inevitable that the book would become part of our country’s ongoing debate about race and racism. We feel good about taking a social activist role and are willing to accept criticism from those with alternate viewpoints. We don’t expect to change the minds of those who don’t view racism as a problem or who don’t agree that implicit racial bias exists. However, we believe the book can be helpful in activating the “silent majority” of White Americans to be more vocal, at least with their children.

7. What are tips for helping readers to see both sides of an issue?

One interesting issue with two sides is the debate about color-blind vs. color-conscious parenting. Psychological research documents that most White parents tend to use a color-blind approach. That is, they avoid directly discussing race, not wanting to sensitize children to racial differences, which they fear may increase prejudice. In the past, the pros and cons of each approach have been extensively discussed in the psychological literature. However, consensus seems to be emerging that the color-conscious approach is more helpful in reducing prejudice among children.

Obviously our book embodies a color-conscious approach since the story text is explicit in discussing race and racial injustice. Yet, we wanted the book to appeal to those parents who have used a color-blind approach or aren’t sure about the best approach. So, in our appendix for parents, we empathize with the challenges of discussing race with children. And we do what most authors do – try to help them understand the perspective of an important “character” with an alternative viewpoint – in this case, their child. We provide parents with some relevant information about child development (e.g., young children inevitably notice skin color and tend to ascribe positive qualities to the group that they belong to). We let parents know how their children might be interpreting their silence (e.g., race is a taboo topic) and point out the impact that media stereotypes, others’ comments, and observed disparities can have on their children’s attitudes. Since all parents want to have input in shaping their children’s values, we hope this information will contribute to more color-conscious parenting, without parents feeling criticized for an initial color-blind approach.

8. You wrote SOMETHING HAPPENED IN OUR TOWN with Marietta Collins and Marianne Celano. What was that process like? How was it different from writing alone?

It was fun to collaborate, sometimes by brainstorming together and sometimes by providing feedback after one author had drafted a section. We had worked together before on various projects, but never on a fictional story. However, our shared history had created levels of respect and trust that allowed us to be open in expressing our ideas and feedback.

It is different writing with others as opposed to alone. In some ways, writing alone seems easier. You set your own timetable and sometimes ideas just flow, when you are “in the zone”. The collaborative process at times feels less creative and more analytical.

On the other hand, I think collaboration was incredibly valuable for this book. All of us made essential contributions that made the book stronger than it would have been if authored alone. Because I had worked as a psychologist with families of many different ethnic backgrounds, I had a good sense of the challenges faced by African-Americans. Still, I felt it was essential to have the insights of my co-author Marietta Collins, who is Black, to create a story that authentically represented an African-American perspective. My other co-author, Marianne Celano, provided particular expertise in child and family reactions to traumatic events.

9. What inspired you to write the book? Was there a particular event that was the “final straw” where you all said, “We must do something about this?”

In the past few years, all of us have felt concerned about the increased divisiveness in our country and more open expressions of racist sentiments. For me, one memorable event was the shooting of Philando Castile in July 2016. He was pulled over by a policeman and informed the policeman that he had a firearm in the car, in an apparent attempt to be transparent and avoid misperceptions. His girlfriend and her young daughter were also in the car. Nevertheless, Philando was shot as he reached for his identification, according to his girlfriend. I remember thinking “What in the world is a Black man supposed to do when he is pulled over by a cop to avoid being shot?” I also remember thinking about how traumatic this event was going to be for the child witness. While the children in our story do not witness a shooting, we did want to address the issue of children’s vicarious trauma from hearing about police shootings.

10. What is your next writing project?

We are energized about topics in which social issues intersect with children’s and families’ daily lives. These topics include controversies about economic disparities, consumerism vs. environmental protection, and screen time vs. direct social interaction for children. We are also interested in the topic of school shootings, although if we wrote about that issue we would likely target older children or teens.

—

Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice

Something Happened in Our Town describes a traumatic event—a police shooting—from the perspective of a White family and an African American family. This story models productive conversations around racial-ethnic socialization and social-emotional learning, and provides an excellent platform for discussing social justice and race relations with children. Includes a “Note to Parents and Caregivers” with conversation guides, child-friendly vocabulary, and lists of related resources.

Something Happened in Our Town describes a traumatic event—a police shooting—from the perspective of a White family and an African American family. This story models productive conversations around racial-ethnic socialization and social-emotional learning, and provides an excellent platform for discussing social justice and race relations with children. Includes a “Note to Parents and Caregivers” with conversation guides, child-friendly vocabulary, and lists of related resources.

Category: Interviews