On Writing Psychological Suspense

How to Make a Friend grew from my desire to explore what happens to unhappy and lonely children when they become adults. Having been in that situation myself I know that it is possible to lead a perfectly normal life, to make friends and build good relationships, but that it never leaves you completely.

There will always be something in the back of your mind, a little troll to remind you that you are a fraud; that you are in fact as weird as you were as a kid, no matter how cleverly you have learnt to hide it. What if something happens to bring those feelings out of the dark and into the light?

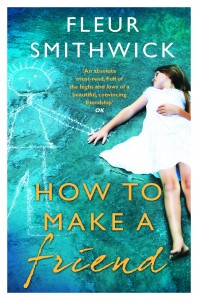

At the beginning of How to Make a Friend my protagonist, Alice, is functioning well; she has friends and a budding career as a fashion photographer that she’s worked hard for. The unhappy memories of her childhood have long lost their ability to cause pain and she is content. It takes the death of her closest friend to remind her how fragile her victories have been.

When my editor at Transworld told me that I’d written a psychological suspense, I had no idea what she was talking about despite having read my fair share of books like Before I go To Sleep and Gone Girl. I am one of those writers who have folders full of novels that didn’t make it and over the years I’ve attempted different genres.

How To Make a Friend came from an ‘Oh sod it,’ moment, when a ‘chick lit’ novel I’d written failed to pique the interest of an agent. The logic was simple: To hell with trying to write what I think people want to read, I’ll write something for myself. It was going to be my last attempt (it probably wouldn’t have been!). I sat down and began the story of a woman whose imaginary friend invades her adult life. I must have written the right thing at the right time because everything fell into place after that.

How To Make a Friend came from an ‘Oh sod it,’ moment, when a ‘chick lit’ novel I’d written failed to pique the interest of an agent. The logic was simple: To hell with trying to write what I think people want to read, I’ll write something for myself. It was going to be my last attempt (it probably wouldn’t have been!). I sat down and began the story of a woman whose imaginary friend invades her adult life. I must have written the right thing at the right time because everything fell into place after that.

People can be snobbish about labels, but I was delighted to unexpectedly gain one. I want people to read my books. As for the mechanics of the genre, of any genre in fact, what is important is what you make of it, what you put of yourself into it.

It has to be honest. Having said that, there are some things that many psychological suspense novels have in common and that have become part of the reader’s expectation; certain parameters within which it is helpful to stick to if you want your book picked up and marketed effectively.

- A severely limited cast. A Ruth Rendell novel, say, The Keys to The Street, has a large number of characters, at least a dozen of whom get their point of view represented. That isn’t what is wanted here. Two main characters wouldn’t be too few. Half a dozen is probably too many. Think about older books like Misery. Stephen King puts two people in a room and keeps them there for almost the entire novel. And Mrs Danvers dominates Mandalay, tormenting her naïve new mistress. We remember Max de Winter, but we don’t dwell on him.

Then there are the real-life stories. With twenty-four hour news, it seems that we get told about every murder and bizarre death that happens anywhere in the world. It makes the improbable feel possible. Why would we let our children leave the house when monsters like Ian Hunter may be waiting to take them? The stories of Josef Fritzl, Harold Shipton and Fred and Rosemary West come to mind with all their small neighbourhood horror. There are good reasons why we follow these stories so avidly. They are Every-Man and their victims are us.

- The threat. The threat should be as close to home as possible. Put it in the fridge if you can make a story out of that. Readers of the genre aren’t looking for a big external issue – political intrigue, serial killers (unless they are married to one) or bomb threats. So no conspiracy theories or car chases; just extraordinary things happening to very ordinary people. Their world is their streets, their train, their neighbours, their family. The writer should use our own fears and weaknesses to ambush us.

- Emotional Catastrophe: When someone dies, it matters. This is The Killing not Midsomer Murders where the victim’s closest relatives seem to brush off the trauma like snow from their shoulders. This is real pain and devastating personal consequences. Damaged people damaging those that love them.

- Murder is not a prerequisite. This isn’t about forensics or imaginatively perverse ways of torturing and killing a victim. It’s more about emotional assault. It’s about how our vulnerability, whether it be drugs, loneliness, drink, promiscuity or mental health issues make us behave in ways that invite disaster and tragedy, that give bad people their opportunities. The character has more than one battle to fight, but it’s the one she’s fighting with herself that should fuel the novel. I say ‘her’, but it could just as well be ‘him’.

The human psyche is a treasure trove; the way we react to events, the way people react to us varies as greatly as our fingerprints and DNA. We are the story and that is why we read them.

—

Born in Brighton, Fleur studied French Literature at Southampton University and worked in various jobs, including twelve years as a school secretary, before becoming a full-time writer. She has won several short story prizes, and her first novel How to Make a Friend is published by Transworld. She lives in London with her husband and two children.

Follow her on Twitter @FleurSmithwick

Find out more about her on her Website http://fleursmithwick.com/

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

Thank you for the wonderfully clear and concise explanation. Since I’ve realized that my book, which I though to be a complete misfit genre-wise, actually fits into the subgenre of psychological suspense very neatly, my eyes have opened to all kind of possibilities.

I love the four requirements you’ve outlined in the article, especially the “no violence prerequisite”. In my own story, the threat to the heroine comes from losing her mind, it’s a mental health issue, a very quiet horror. Any other books in the same line (besides the much-discussed Girl on the Train) you could think of? Experimental prose is welcome. Many thanks in advance!

Love the article. Looking forward to reading more 🙂