One Writer’s Beginnings: The Bitter Gift of Trauma, by Barbara Quick

“For any novel—or any poem, for that matter—to really speak to readers, there has to be emotional juice there for the writer.”

by Barbara Quick

I grew up in Los Angeles in the 1950s and ‘60s. My father was an extremely sensitive, artistic, and intelligent man who, from, the get-go in his marriage with my mother, became an abuser. His violence was mostly directed at my mother, occasionally at my brother. All of us were terrorized by my father’s displays of frustration and rage, which involved a crescendo of yelling and crashing about that led to a violent act, followed by our withdrawal to safety and, eventually, his remorse.

I grew up in Los Angeles in the 1950s and ‘60s. My father was an extremely sensitive, artistic, and intelligent man who, from, the get-go in his marriage with my mother, became an abuser. His violence was mostly directed at my mother, occasionally at my brother. All of us were terrorized by my father’s displays of frustration and rage, which involved a crescendo of yelling and crashing about that led to a violent act, followed by our withdrawal to safety and, eventually, his remorse.

My father always seemed to love and admire me as much as he attacked and belittled my mother. It made for a really toxic triangulation situation between my mother, my father, and me: the more he showed me behavior she saw as belonging, by rights, to her, the less she could co-opt and feel good about the milestones of my childhood.

Summer theater, and theater arts classes throughout high school, provided an escape from the sturm und drang of my family life—and gave me, every season, a new pretend-family with whom I could interact and work at being loved.

It was only after the publication of my second novel, Vivaldi’s Virgins—the story of a girl growing up in a foundling home in 18th century Venice—that I came to recognize my own orphan scenario: the well-spring of mother-love that was taken away from me; the resulting self-doubt and psychic pain. Once I’d done the bulk of my research for the novel and began writing, it felt as if the inner world of my orphan protagonist, Anna Maria dal Violin, was fully accessible to me—because I could remember precisely what it feels like to be without the protection of a mother or father, afraid, uncertain and abandoned; dependent on one’s own determination, ambition, and grit.

Writing literary fiction requires a highly tuned degree of empathy of the sort that’s typical of the best therapists, an ability and willingness to look inside people’s words and behavior, and explore the buried trash and treasures of their past: all that makes them who they are; all that makes them conceal who they are, from themselves and others; shining a light to try to find all the gleaming little keys that might fit the locks of their most hidden places.

For any novel—or any poem, for that matter—to really speak to readers, there has to be emotional juice there for the writer.

Novels Can Take a Very Long Time to Ripen

The life-path of a novelist is always strewn with unfinished or abandoned manuscripts, books that haven’t found a home and books made from stories whose time has not yet come.

Photo by Judith Lindbergh

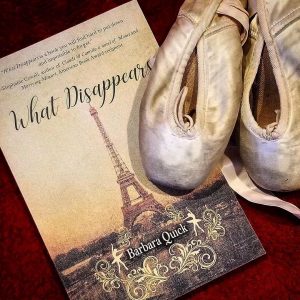

What Disappears, my fourth novel, was one such story for me. I began writing it when my narrative skills didn’t extend beyond those of a confused twenty-one-year-old poet who’d never attempted an extended work of fiction before.

The novel started out as a series of sketches based on whatever stories I’d been able to wrest from my taciturn but beloved maternal grandmother—aka Nana—about growing up in a family of politically leftist, largely secular Jewish tailors in Kishinev, under the Russian Tsar. I learned from Nana that her family’s commission to make the hats and coats for the local parochial school led the parish priest to shelter them in the attic of the church during the horrific pogrom of 1903.

Taking up the story again, decades later, I did compendious research about the history of the Jews in Russia, the history of ballet and the Belle Époque in Paris. The work expanded far beyond its original borders and intent, into a multi-generational story of love, loss, art, and social change. But my description of Sonya’s youthful passion for Jascha, the pharmacist’s son—and their first kiss underneath a streetlamp, in the snow—is nearly word for word the way I first wrote it.

The theme of the lost sister—the separated twins—didn’t take shape until my own little sister made her decision to shut me out of her life.

I’ve struggled to understand how someone I loved so much ended up not wanting to have anything to do with me. I left home for college when I was seventeen and she was only eight years old. I was far away and really had no idea what was going on in her daily life as a latch-key kid. And, as people do, I was looking out for myself: in rescuing myself, I abandoned her, even though it didn’t feel like that to me at the time. Awakening to her feelings was a process that took many years of obtuseness on my part. It was a rejection that didn’t seem possible until, suddenly, it was a hard-and-cold fact.

My sister’s disappearance from my life—and the pain I’ve felt about it—fueled my character Sonya’s search for her long-lost twin in What Disappears. Again, I didn’t fully understand that aspect of the story’s personal and psychic relevance for me until the novel was done.

Nana told me that her mother used to take the train to Paris twice a year to see the fashions. I was always mystified and enchanted by this factoid, which didn’t seem to belong to the otherwise provincial and unglamorous life and family she described. In trying to find a way to make sense of this unexplained Paris connection, I let the story leap outside the boundaries and timeframe of Nana’s life, into the glittering world of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes—into a time and place, and a set of circumstances, in which my fictional sisters, at least, could live out the possibilities, with all its complexities, of a reunion.

—

Barbara Quick is best known as author of the 2007 novel Vivaldi’s Virgins, translated into over a dozen languages, made into an audiobook, still in print and currently in development as a mini-series by award-winning director Agnieszka Holland. Winner of the Discover: Great New Writers prize for her first novel, Northern Edge, Barbara was awarded the 2020 Blue Light Press Poetry Prize for her debut chapbook of poems, The Light on Sifnos. Barbara’s fourth novel, What Disappears—over a decade in the making—was published by Regal House on May 17th. Her 2010 novel from HarperTeen, A Golden Web—about the 14th century teenage anatomist Alessandra Giliani—continues to intrigue and attract historical fiction fans. A trained dancer and avid organic gardener, Barbara is based on a small farm and vineyard in the California Wine Country with her husband Wayne Roden, a vigneron and long-time violist with the San Francisco Symphony. More at BarbaraQuick.com

WHAT DISAPPEARS

Category: On Writing

What Disappears is a gripping multi-generational tale that begins in Tsarist Russia in the late 19th century and ends in Paris with the start of the First World War. Jeannette Dupres, one of two identical twins born to a Jewish family in dire political and financial straits, is spirited away as an infant by a Catholic family in France. The other twin, Sonya Luria, who was told her sister died at birth, has her life upended by the 1903 pogrom in Kishinev.

What Disappears is a gripping multi-generational tale that begins in Tsarist Russia in the late 19th century and ends in Paris with the start of the First World War. Jeannette Dupres, one of two identical twins born to a Jewish family in dire political and financial straits, is spirited away as an infant by a Catholic family in France. The other twin, Sonya Luria, who was told her sister died at birth, has her life upended by the 1903 pogrom in Kishinev.

Beautifully written article!