Telling The Story Without Knowing The Answers

On New Year’s Eve, a year after my mother died, my father said, “I want you to tell her story.” In any family this would be an awkward moment, but in ours it was an invitation to dance in a field filled with buried landmines waiting for the foolhardy to set off an explosion. “Not a chance,” I said. Two years later, I had a first draft.

On New Year’s Eve, a year after my mother died, my father said, “I want you to tell her story.” In any family this would be an awkward moment, but in ours it was an invitation to dance in a field filled with buried landmines waiting for the foolhardy to set off an explosion. “Not a chance,” I said. Two years later, I had a first draft.

My father died in Manhattan on February 1 of this year, and never saw the publication of “his” book, which came out on my mother’s birthday, April 23, 2020. Our family’s story is one of secrecy, half-truths, and missed opportunities for intimacy. It turns out that this is not terribly unusual for survivors of the Holocaust and their progeny, but until the lid was torn off that secrecy in the past ten years with the exploration of second-generation trauma, no one talked about it. Leave it to us, the generation that considered ourselves the center of the universe, to make it about us, the children of the survivors, when the survivors did all they could to make it not about them.

On that fateful New Year’s Eve I sat at the dining room table with my father, who despite his age retained absolute clarity, a strong voice, and diction that displayed his vast education and elevated culture. The big secret, that he was born poor in a mining town in Western Pennsylvania, when Jews couldn’t play tennis on certain courts or live in particular neighborhoods or apartment buildings, could not be discerned in his voice.

Pulled out of school at 18 to serve in final weeks of World War II, he vowed that if he returned alive he would be a new man, one no one would ever be able to take advantage of. Only late at night did that midwestern flattening of the vowels in mid-sentence, so typical of Pennsylvania-Ohio, come out. Never did he utter a word of Jewishness, but he demanded equality and treated everyone as equals.

That day, in his melodious voice, he told me the stories he knew of the Polish Jewish beauty that he managed to marry. This magnificent creature arrived in Philadelphia after the war, with no past, no family, no story. She was stunningly beautiful, looked like a Spanish flamenco dancer, could speak six languages, smoked constantly, and could shred a man’s ego in two charmingly-accented sentences. He proposed on the first date, the second, and the third, and was accepted on the fourth. He wanted nothing but her future.

How was this her story, I asked. But typically, it was his.

As the long day wore on and he got tired– he was, after all, in his late 80s–the tone began to change. “She walked out, you know. Her parents were already gone. She’d been the best student in her class… she spoke perfect German, Polish…they put her to work in the factory…she was beautiful, the guard called her his little dumpling, he had plans for her…she knew what that meant.”

She was fifteen, she walked out of the Warsaw Ghetto, and into a life where she never said her real name again. She was exotic, she was brilliant, and she suffered unspeakable crimes, but she survived on her beauty, her brains, her cunning, and her courage. And her willingness to turn her memory off.

There was a strong midwestern twang as the stories went on. I had my phone recorder on, and I asked a question now and then, but mostly my father talked. And then I noticed that the stories started to change. They happened in different places. There were no men. The secrecy started to return. He was tired, he was going to bed.

The next day he said he didn’t remember any more stories about my mother. But I did. Stories she half-told, stories she alluded to. I knew I couldn’t write the book as non-fiction, because I didn’t know what was true and what wasn’t. All I knew was that my mother was truly courageous, and that her story wasn’t going to fit in with the romanticized, idealized vision that so many people have of Jews in World War II.

She couldn’t tell her story because we want our heroes to be perfect: perfectly heroic, or perfect victims. The terrible, complex choices that real people made every single day are too disturbing to accept. We want the story to have a moral. The good guy wins—or even, nice guys finish last.

But life is complex, and when my mother chose to put her past in a box and seal it, it was a complex choice. The seals leaked. My sister and I heard different stories, saw conflicting sides of her. We took away inconsistent visions of the same woman. And we never told each other the stories, out of fear that one of us would reveal something neither of us could live with.

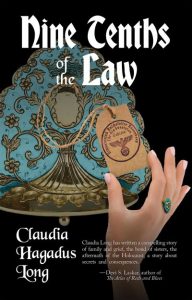

One day, over forty years ago, my mother and I went to the Jewish Museum in New York City, and she showed me the menorah that’s at the center of Nine Tenths of the Law. “We had one just like that,” she said to me. I was young enough not to pursue it, old enough that I should have. She touched the glass case and said it again. She was telling me, That was mine.

It’s with that memory of my own that the book starts. It’s tied together with my mother’s stories, but it’s a book about sisters, really, a book of the survivors’ children. There’s a mystery, there’s humor—what’s a Jewish book about tragedy without humor?—and there’s love. I wish my father would have lived a few more months to see the book (though he would not have survived the pandemic in New York City at 92.) He would have read it. He would have loved it—he loved all my books. And he would have said, “You can’t talk about this.”

It’s okay, Dad. It’s fiction. No one will know.

—

Claudia Hagadus Long

Claudia Hagadus Long is the author of Nine Tenths of the Law (Kasva Press 2020) as well as three historical fiction books that center on Colonial Mexico and the Crypto-Jews, and one book about women in the labor movement in 1920 San Francisco—as told through the eyes of a prostitute. She is a lawyer-mediator and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

NINE TENTHS OF THE LAW

Two sisters, their mother, and a Nazi thief.

In 1939, a beautiful enameled heirloom menorah was looted by the Nazis, grabbed from the hands of its young Jewish owner. Too beautiful to kill, Aurora herself was singled out by the SS for “special duties.”

In 1939, a beautiful enameled heirloom menorah was looted by the Nazis, grabbed from the hands of its young Jewish owner. Too beautiful to kill, Aurora herself was singled out by the SS for “special duties.”

Eighty years later, Aurora’s daughters Zara and Lilly discover the family menorah in a New York museum. Haunted by their mother’s buried memories, the sisters scheme to get it back—but their quest takes a dangerous turn when the menorah disappears, leaving a trail of murder and mayhem behind it.

Aurora’s memories, it turns out, are very much alive; and now her secrets can bind the sisters together or tear them apart.

BUY THE BOOK HERE

Category: On Writing