The New Thirst For Words

The rise of ‘text speak’ and ‘twitter talk’ appears to have triggered a desire for more challenging and imaginative vocabularies – something writers should welcome and embrace.

The rise of ‘text speak’ and ‘twitter talk’ appears to have triggered a desire for more challenging and imaginative vocabularies – something writers should welcome and embrace.

In Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, a depleted language (Newspeak) is used by a totalitarian government as the ultimate means of control and repression. Each year the government reduces the number of words available to its citizens. Without words to express their ideas or feelings, they become powerless automata. Orwell’s dystopian world is a salutary reminder of why a rich vocabulary is essential.

Words are tools of thought – instruments for enabling us to grapple more effectively and more precisely with thoughts, ideas and emotions, our own and those of other people. This is the territory of fiction. It’s partly the size and depth of our vocabularies that enable us to do this. And creative writers reign supreme when it comes to vocabulary. Indeed, research has proven that readers of fiction have larger vocabularies than anyone else. We may despair at the impact of Social Media on language, but I believe we’re facing a new dawn, a linguistic backlash that plays to the strengths of fiction writers everywhere.

Last year’s Costa prize-winning YA novel, The Lie Tree by Frances Hardinge, is so verbally extravagant I almost cried with delight. Not just because of the novelty of such language in a recent YA novel, but because of its recognition by a commercial prize like Costa.

A few weeks later I had a similar experience when I read Anna Hope’s widely acclaimed The Ballroom. By this time the dictionary app on my iphone was almost blazing. I gave The Lie Tree to my thirteen-year old daughter (who speaks in a series of snapchat LOLs) expecting her to be flummoxed. Quite the reverse. She adored it. She too now has a dictionary on her iphone. Ironically, the convenience and ubiquity of the dictionary-on-a-device has made challenging language accessible and enjoyable for us all.

Those of us writing in English are particularly blessed. The Irish writer, James Joyce, refused to write in any language other than English. He was multi-lingual in French, German and Italian, and his Irish compatriots – in their zeal for independence – urged him to write in Gaelic. But he was adamant that only the English language had a vocabulary rich enough to achieve his grand ambition: to fully articulate the human condition.

As I researched my first novel, I read hundreds of books from the early twentieth century and became increasingly excited by the variety of words authors routinely used then. I began jotting down every word I didn’t know. To my shame (I have a degree in literature), there were lots. While some of these were words I simply hadn’t come across, many were words that have fallen out of use. I always tried to guess the meaning before I reached for the dictionary. Interestingly, my guess was frequently right, because the meaning of a word is often implicit in either its context or its sound.

In The Ballroom, Hope resurrects old Yorkshire dialect. I’ll admit many of these words weren’t in my iphone dictionary. But a dictionary wasn’t necessary – these ancient words were decipherable through their sound and rhythm. While they weren’t terms I could pilfer for my Paris-based novel, they added a layer of richness and authenticity to her Yorkshire-based novel.

They also challenged me to think more deeply about how and when we should best use unfamiliar words and dialect in fiction. Re-reading DH Lawrence showed me how fine the line is between richly-readable and irritatingly-unreadable. His vocabulary was impressive but his use of Nottingham dialect was often overdone and impenetrable.

I found something similar in Joyce’s writing. His display of linguistic dexterity in Ulysses was inspirational. But he overstepped the mark in Finnegan’s Wake where his inventiveness became a morass of illegibility.

For my own novel, I had to research Dublin dialect for the speech of Nora Joyce. I relied heavily on the plays of Sean o’Casey – and fell in love with the Dublin-speak of the 1920s. But I was careful to select only the odd word – and words where the meaning became clear through the context. I loved the word ‘chiselers’ (children) for example.

For my own novel, I had to research Dublin dialect for the speech of Nora Joyce. I relied heavily on the plays of Sean o’Casey – and fell in love with the Dublin-speak of the 1920s. But I was careful to select only the odd word – and words where the meaning became clear through the context. I loved the word ‘chiselers’ (children) for example.

I wanted to use it everywhere but I restrained myself, finally using it only once: “You’re like a pair of chiselers who’ve been at the sweet jar”. The context made the meaning clear. The simplicity of the sentence made the word stand out. The same rules apply to using more complex or unfamiliar words: use them sparingly, use them carefully. Think of them as spices. Not many of us enjoy an overly-hot vindaloo – and not many of us like overwritten, purple prose.

The masters and mistresses of children’s writing (Roald Dahl, Edward Lear and JK Rowling, for instance) have consistently used bold, imaginative language to enthral and delight. I think it’s time for more of us to do the same – to challenge our readers with expanded vocabularies, to play with our astonishing language, to resuscitate old words, to weave the extraordinary into the ordinary. Our readers are ready!

I keep this paragraph from Ulysses above my desk. It might irritate pedants but it always makes me smile. See if you can spot Joyce’s invented words…

“Flaskets of cauliflowers, floats of spinach, pineapple chunks, Rangoon beans, strikes of tomatoes, drums of figs, drills of swedes, spherical potatoes and tallies of iridescent kale, York and savoy, and trays of onions, pearls of the earth, and punnets of mushrooms and custard marrows and fat vetches and bere and rape and red green yellow brown …ripe pomellated apples and chips of strawberries and sieves of gooseberries, pulpy and pelurious, and strawberries fit for princesses and raspberries from their canes.”

—

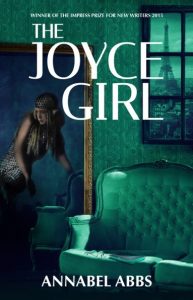

The Joyce Girl by Annabel Abbs was published on 16 June, and tells the story of Lucia Joyce, a dancer in 1920s Paris and the daughter of James Joyce. It won the Impress 2015 Prize for New Writers, was longlisted for the 2015 Bath Novel Award and the 2015 Caledonia Novel Award, and was shortlisted for the 2015 Spotlight First Novel Award. It’s since been sold to several countries including Hachette in Australia and Aufbau-Verlag in Germany.

Annabel Abbs lives with her family in London. Find out more at www.annabelabbs.com, @annabelabbs and www.facebook.com/abbsannabel/

Category: On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post