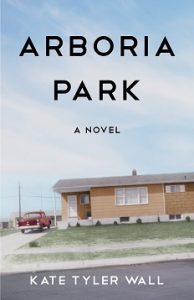

The Real (and Not Real) Arboria Park

Arboria Park was inspired by the place I grew up and lived in until I was twelve: Rodney Village, near Dover, Delaware. That’s my house on the cover of the book. The photo was taken in 1958, soon after we moved in (when I was two months old). The real house was gray, and my father’s Studebaker was dark green. Like Tom and Evelyn in the book, my parents faced a housing shortage when they moved from Maryland to Dover.

Arboria Park was inspired by the place I grew up and lived in until I was twelve: Rodney Village, near Dover, Delaware. That’s my house on the cover of the book. The photo was taken in 1958, soon after we moved in (when I was two months old). The real house was gray, and my father’s Studebaker was dark green. Like Tom and Evelyn in the book, my parents faced a housing shortage when they moved from Maryland to Dover.

Rodney Village was one of several developments responding to the need for housing around Dover. Most of our neighbors were Air Force families, so my friends would usually move away. As is often the case with new neighborhoods, people tended to be close and know everyone else, but the transience of the Air Force and General Foods families broke down that cohesion over time.

We moved to another neighborhood in 1970, in the city of Dover. My parents now voted in city elections and followed local matters more closely. Our new development had a civic association, which meant a bit more political clout. This would become important later.

My mother died in 2013, and my brother Mark and I were faced with cleaning out, fixing up, and selling her house. During that time, we learned that most of a street in Rodney Village (Charles Polk Road) was to be demolished for a connector road from West Dover (where dozens of upscale housing developments, shopping centers, medical complexes, and even the new public high school had been built on former farmland). Various routes had been discussed and discarded; my mom’s neighborhood civic association had helped block one nearby.

I believe one reason Charles Polk Road was chosen was because, unlike my mother’s middle-class neighborhood, Rodney Village was in an unincorporated area outside the city, home to many renters, and a bit run down. In short, it lacked political clout. During the summer of 2013 Mark and I watched in fascination as people moved out of the houses, which were then boarded up.

All of the south side of the street was slated for demolition. One house had been home to some childhood schoolmates. Another had belonged to our mother’s best friend, who died in a car accident in 1970. So we felt a personal connection to arguably one of the nicest streets in the neighborhood. I photographed several of the houses before they were torn down.

I thought a lot about what a good story the neighborhood’s history would make, from its farm origins until it was threatened with destruction. I decided to tell it through the lives of a family who, unlike mine, had kept consistent ties to the community. As the story coalesced, I realized I needed to go beyond Rodney Village and Dover to bring in some other elements, like racism, economic dislocation, and town/university tensions.

I live outside of Newark, Delaware—a college town with its own odd housing history. My house is in another 1950s housing development, which, despite ups and downs, has held on as a diverse, stable community. I plunged into finding the history of similar neighborhoods and added some imaginary elements.

I live outside of Newark, Delaware—a college town with its own odd housing history. My house is in another 1950s housing development, which, despite ups and downs, has held on as a diverse, stable community. I plunged into finding the history of similar neighborhoods and added some imaginary elements.

One was based on a duplex development, built in the 1940s, where I lived briefly (George Read Village in Newark, originally built for munitions plant workers during World War II—like Rodney Village, its history related to military concerns and its streets were named for Revolutionary era Delaware patriots). Houses like these became “the Pines,” a section of Arboria Park that’s always just a little bit poorer and odder, and where succeeding generations of girls in the Halloran family (Mary, Stacy, and Autumn) go to seek both trouble and salvation.

Literature about suburbia is either very upscale, vaguely 1950s in nature (see Cheever, Yates, or the Seinfeld comment about “stockings, martinis, and William Holden”), or about its cookie-cutter, Levittown sameness. Not much comes from a working-class perspective, or acknowledges that some of us have vivid, even good memories of growing up in this slice of Americana, despite its shortcomings and dangers.

So I took my old neighborhood, my current one, and some knowledge of twentieth-century culture, music, and architecture and mixed in an actual event (a road project) with some flat-out imagination. (Arboria Park is a hotbed of punk rock music from the 1970s on, which my real neighborhoods, to my knowledge, are not.) Though its happenings and inhabitants are imaginary, its story is real and deeply rooted in local history.

—

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing