The Stories of Your Life: Ways to Use Autobiography in Your Fiction

A common trope is that everyone has at least one story to tell, presumably the story of their life, but not everyone chooses to tell that story in writing, either as memoir or as thinly disguised fiction. Of course, even those who do write may create worlds, characters, and plots that are far from the facts of their own biography. However, I would venture that all authors call on some aspects of their personal experience as they weave their fictional tales, even if it’s just one character’s quirks that resemble their neighbor’s or a snippet of speech overheard on the subway.

A common trope is that everyone has at least one story to tell, presumably the story of their life, but not everyone chooses to tell that story in writing, either as memoir or as thinly disguised fiction. Of course, even those who do write may create worlds, characters, and plots that are far from the facts of their own biography. However, I would venture that all authors call on some aspects of their personal experience as they weave their fictional tales, even if it’s just one character’s quirks that resemble their neighbor’s or a snippet of speech overheard on the subway.

As a writer whose history inspires much of my fiction, I’ve thought about the various ways that I’ve used my life’s content to inform premise, subplots, characters, emotional veracity, setting, incidents, and dialogue, especially in my novels. I’ve also considered the pitfalls in trying to stay too close to real life.

Premise. What is your story about? Here, I am not referring to the details of the plot or the broader themes, but rather the essential spine that can be summarized in a few words. A premise inspired by your life’s events can be a rich jumping off point. In one of my as yet-to-be-published novels, the premise of two best friends writing their own novel together comes directly from my own life although most of the plot has little relationship to the facts.

But tying your premise and what follows too intimately with real life events can send you down some writing rabbit holes, such as lack of tension, pacing issues, extraneous characters, scenes that don’t add valuable information, and even lack of believability. “But that really happened,” you protest. Truth doesn’t matter if the reader isn’t buying it.

Subplots and scenarios. It’s difficult to base a whole plot on your biography because most people’s lives are much messier than that. Even in memoir, the writer must find the arc on which to hang her story. But life can make for some plausible subplots that feed into and support the larger story. For example, in my novel of two friends writing a novel together, a boss throws up roadblocks to career advancement for one of my main characters, who is an academic. The overall scenario and its emotional impact, although not the particulars, closely resemble my friend’s experiences and are germane to the advancement of the bigger plot.

Characters. Basing characters on real people can inject the all-important feeling of three-dimensionality, even in secondary characters. Mixing and matching is allowable, too—Uncle Charlie’s big nose and mutton chop sideburns with cousin Ben’s skepticism and sarcastic wit and friend David’s habit of brushing his fingers across his hair when he’s annoyed–as long as these traits feel compatible and add something to the story. Real people who play smaller roles in your story can also be combined for efficiency’s sake to avoid a surplus of characters.

Some people are hard to resist as total packages, and then the fear is that they or someone they know will recognize them—not a problem if the comparison is kind or even amusing, not so great if the representation is uncomplimentary. One of the hardest character traps is basing one of your main characters on yourself. Can you detach sufficiently to paint this fictional you in a believable manner, making needed changes that will improve your overall story? Inevitably, readers who understand that your own life served as inspiration for your protagonist will want to grant you your character’s whole biography, even if most of it is made up. In my forthcoming novel, inspired by some of my experiences decades ago, my protagonist becomes a prostitute. When I explain that I personally didn’t do that, I often get a wink-wink. Writers, beware!

Emotional veracity. As readers, most of us like to feel the emotions of our characters as they move through and react to different situations. If you’ve been in similar situations, you may be able to find ways to express yourself that allow others to go along on the same ride. But even if your protagonist’s (or secondary character’s) journey is different from yours, you can still capture the emotional essence by channeling times when you felt the same emotions.

Here again, it’s easy to fall prey to stereotypes of how a character should feel rather than the often more nuanced, multiple, and/or conflicting array of emotions that complex experiences prompt. In addition, your personal emotional response may not be a believable one or the best one. In my forthcoming novel, my protagonist manages to fend off a man who is trying to rape her. In my own life, after such an experience, I recall moving past it somewhat quickly. That’s the way I wrote the scene initially, but my beta readers weren’t having it.

Setting. Authors often set their novels in the places they know—consider Anne Tyler’s Baltimore or Dennis Lehane’s South Boston. These places can become their own characters, affecting the course of action that a protagonist takes or the obstacles they meet. Or, they can be evocative backdrops, whether set in the present or another time. Settings from your life need not be as expansive as a whole city but could be as small as the corner drugstore with its soda bar where you hung out as a teen or the office with cubicles that you couldn’t wait to escape. Including rich description of familiar places makes them come alive, especially when you cover all the senses.

One danger with familiarity is in providing too much detail at the wrong times, and thus, diluting the tension. Another challenge is becoming obsessed with presenting your known setting with one hundred percent accuracy. An easy solution to this problem is to make up a new name for that small town in Vermont where you grew up, or to fictionalize that restaurant in New York City that was inspired by the Carnegie Deli, but isn’t the Carnegie Deli. Your bigger settings can be a combination of the real and fictional. In my novel set in Tokyo, my protagonist visits real places, changes trains at a real train stop, but travels on a fictional train to a fictional part of the city where she lives.

Incidents. Incidents are not plot but can provide the fuel for plot. X happens and sets the plot in motion. Y happens, and everything shifts direction. Incidents from your life can be the stuff of whole scenes, flashbacks, or sidebars that provide context to the current emotional state of a character. I love using incidents from my life in fiction. My ultimate adolescent humiliation took place at the eighth-grade sock hop. I’ve used it in two different unpublished novels—one in current time and one as a flashback.

Like everything else, incidents need to be germane to the story. As with setting, deciding how detailed to be is crucial. Inevitably, you will need to kill several your incident “darlings” upon revision, as hard as that is. I once had a long scene about a one-night stand my protagonist has with a soldier. That happened to me, but neither the soldier nor the incident was germane to the already over-long story, and I cut it, somewhat sadly.

Dialogue and Gesture. I am a dialogue nut. My stories are heavy with dialogue, probably because I spent a few years writing screenplays before I shifted to novels. But I am in awe of people who, in describing something that happened to them, appear to repeat whole swathes of speech. My memory doesn’t work that way. I can capture the essence of someone’s style but not their exact words. I can’t even remember what I’ve said myself. Personally, I enjoy eavesdropping on conversation, watching gestures while others talk, and then making some notes to use in my writing.

Translating what you hear into interesting and plausible dialogue takes some work. Written dialogue is rarely an exact representation of actual speech. Superficial greetings (“hi, how are you?” “I’m fine”) and all the “ums” and “uhs,” repetitions, and the back- tracking will make your readers yawn. Like other aspects of writing, dialogue needs to inform the reader about your characters and the unfolding plot. Sometimes, you just have to delete that fabulous line.

Other life artifacts. Each of us owns objects that have personal meaning. In writing, these same objects can also serve as metaphors. Like setting, they can even become their own characters. Favorite music, art, books, and plays, and the feelings they inspire may find a place in the narratives you create. In truth, the list of the parts of your history that you can use is endless as long as you don’t get so attached that you can’t part with something that isn’t working.

Your life is a treasure trove for your writing. Ultimately, your own story doesn’t have to be one story, but can infuse all your writing in a myriad of ways–enlivening it, providing it with veracity, and ultimately becoming your own private kaleidoscope of your life.

—

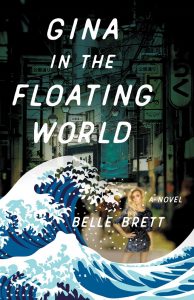

Belle Brett is a writer and artist living in Massachusetts. Her debut novel, Gina in the Floating World (She Writes Press, September 2018), was inspired by people she met, the setting, and experiences she had as a bar hostess in Tokyo but, she emphasizes, is not autobiographical. You can find out more about her and her writing on her website at www.bellebrett.com.

About GINA IN THE FLOATING WORLD

A bank internship in Japan’s booming 1981 economy is supposed to be twenty-three-year-old Dorothy Falwell’s ticket into a prestigious international MBA program. But the internship is unpaid—so, to make ends meet, she accepts an evening job as a hostess in a rundown suburban bar, a far cry from the sensuous woodblock prints she’s seen of old Tokyo’s “floating world.”

Like her namesake, Dorothy hasn’t planned on the detours she encounters in her own twisted version of Oz. Renamed Gina by her boss, she struggles with nightly indignities from customers and confusing advice from new friends. Then her internship crumbles and the suave but mysterious Mr. Tambuki offers help. How can she resist?

With patience and the utmost respect for her opinions, Mr. Tambuki lures her into his exotic world of unorthodox Zen instruction, erotic art, and high-octane sex. Soon, bizarre sexual escapades with monks, salarymen, and gangsters begin to feel normal until one of her clients goes too far, and Dorothy realizes she’s in over her head. But can she find her way back from this point of no return?

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, How To and Tips

You should consider becoming a writing teacher- excellent points articulately explored and substantiated!