The Writing Process for Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman: Public Mystic and Freedom Fighter

The Writing Process for Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman: Public Mystic and Freedom Fighter

Therese Taylor-Stinson

As a Black woman, Harriet Tubman has always been on my radar. She has always stood as one of our sheros during enslavement and beyond. However, in recent years, Harriet has been reintroduced to me by organizations like the Community Healing Network, Inc. (CHN), and the Association of Black Psychologists (ABP), both to whom I was first introduced at a series of Congressional Black Caucus events in Washington DC.

As a Black woman, Harriet Tubman has always been on my radar. She has always stood as one of our sheros during enslavement and beyond. However, in recent years, Harriet has been reintroduced to me by organizations like the Community Healing Network, Inc. (CHN), and the Association of Black Psychologists (ABP), both to whom I was first introduced at a series of Congressional Black Caucus events in Washington DC.

I am a third generation native of DC on my maternal grandfather’s side of the family, and I have lived and worked all of my life in DC predominantly for the Federal Government. I actually tried to avoid Government service, which I referred to as the “family business,” but through those before me and my own Federal service, I found in my retirement how my skills were developed and strengthened, among them my writings skills, and as a bonus, the entire editorial and publishing process through my years as a program analyst, publishing mandated information for the White House.

Through the CHN AND ABP organizations, I was trained and certified as an Emotional Emancipation Circle facilitator, and I deepened my appreciation for the Congressional Black Caucus, whose events had allowed me the pleasure to enjoy an annual celebration of the Black family, government, and DC.

There is a Chinese saying, “May you live in interesting times,” which a contractor that worked for me during my Federal career replied, “You know that’s a Chinese curse, don’t you?” My response was that I have indeed lived in interesting times, as a Black child in Washington DC, born a little over a year before the Brown vs. Board of Education decision regarding desegregation, which even now, has not fully occurred.

I lived through the final wave of the Great Migration, as described in Isabella Wilkerson’s book The Warmth of Other Suns. I lived through the Civil Rights Movement, and rode through the downtown riots in DC to our home “uptown” with my mother, who also was a career Federal employee. I lived through the war in Vietnam and the draft that sent many of my male peers, neighbors, and classmates to fight, and returning broken, drug addicted, and traumatized beyond the trauma already carried as the children of enslaved ancestors.

I lived through “the Bay of Pigs” with Cuba and the bomb shelters created in our neighborhoods in case of war, planes flying overhead. I lived in a Black neighborhood that was under curfew during the riots where National Guard and other military were housed on the grounds of our local high school. Our Black neighborhood was large and strong, with people from every walk of life and many locations South, the Caribbean, and Africa, and we took care of one another as family. I never saw these interesting times as a curse, but a chance to learn, discern, and grow.

So, in my now later years, I began to think a lot about Harriet and the emotional freedom she must have held to accomplish her great feats of liberation of our people, maybe even some of my relatives. What were the circumstances that allowed her to perform these feats of liberation? What gave her the knowledge to heal the sick? Was it deliberate that she stepped between a two pound weight being thrown at a young enslaved boy that struck her on the head instead, creating for her a lifelong condition of narcolepsy?

How was she able, without fail, to hear the voice of the Creator guiding her and her charges to physical freedom, loosing not one? What internalized freedom does it take to accomplish these feats, even dream of them, and to live well into your 90s?

All of these questions reminded me of my readings of Howard Thurman, whose grandmother was enslaved. Yet, Thurman encountered another, more important freedom that starts from within. Thurman wrote of these freedoms in his prose entitled “The Inward Sea” and he talked about these freedoms as “finding the genuine” in oneself in his commencement address at Spelman College, not long before his death.

Thurman could have well been acquainted with Harriet before his death, or his beloved grandmother, Nancy Ambrose, may have influenced him with the stories she knew of Harriet. Surely, Harriet Tubman possessed that internalized freedom. She believed it to be a gift of God. But also, only a generation or two removed from the Africans who traversed the Middle Passage, she more than likely learned the genuine in herself through others in her midst—both family and larger community. On the Eastern Shore, there was more ability to move about, and so she also learned from both free Blacks, like her father and her first husband, and the enslaved still full with the beliefs of those in Africa.

Current Events Regarding Harriet

In recent years, there has been a new flurry of published books about Harriet, including Kate Larson’s, which I encountered in the newly built Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad State Park in Dorchester County, Maryland. I used Larson’s book as my primer, and referenced Sarah Bradford’s depiction to corroborate the facts and to fully understand Harriet’s life and environment. Additionally, I found only one small book written by Linda Cousins-Newton/Amasewa Okomfo that named Mamma Harriet, along with Sojourner Truth, as mystics. There was also the movie in 2019 with Cynthia Erivo as Harriet—a powerful depiction! There was a PBS film about Harriet in 2022 as well. Twenty-twenty-two also marked the 200th Anniversary of Harriet’s Birthday.

It was in 2019 that I led a pilgrimage to the Eastern shore for the Shalem Institute, and wrote the following in the opening of my new book Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman: Public Mystic and Freedom Fighter, which largely influenced my desire to write about Harriet from a spiritual perspective. I wrote, “In Dorchester County, Maryland, one early spring afternoon, in a single line across the sand with other pilgrims on this Tubman journey, I was in awe of the flickers of light reflecting off the water from the noonday sun. Holding sweet gum pods in our bare hands, reflecting on the joy and pain the enslaved endured, we imagined them running barefoot with the abundance of sweet gum under their feet. Through the woods to the river, Harriet was leading them to freedom. We walked to the bank of the river and poured libation as we named our personal ancestors, Mama Harriet among them.

Then we fell silent. In that silence, the wind picked up strength, blowing a soft but forceful presence in our direction. I couldn’t help but believe that Harriet and others we named were before us, welcoming our presence. Slowly, the forceful breeze ceased. I turned with wide eyes to our guide, who stood next to me, and he nodded confirmation. No words. But he knew and I knew we had been visited by our ancestors. This was a mystical experience I will never forget. Now even closer to me are Mama Harriet and her treks to freedom.

I had been one looking for her internal liberation and working toward finding “the genuine” in me as Thurman would express it. That day on the shore of the Choptank River, I was welcomed in by the Ruah (Spirit) of Harriet, and my task became how could I look into Harriet’s life to demonstrate for me and others that internal liberation exists. We all posses the qualities of the Divine, and it is our job to surrender to the call to genuinely know ourselves and our call to our communities for the world.

The Writing Process

Along with the readings of Harriet’s life from Kate Larson’s and Sarah Bradford’s writings, I found, at the time, only one book by Linda Cousins-Newton /Amasewa Okomfo that addressed Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth as mystics. In this book, I found the only clues outside of my experience at the Choptank River of Harriet as mystic, which helped me go back over the more extensive histories of Harriet where I found other clues to her mystical being.

I also took the time to search for information about mysticism in indigenous systems, particularly African belief systems, and there I saw all of Harriet’s spirituality come together authentically from her ancestors, her ties to the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, and even in her episodes of narcolepsy, her understanding of natural remedies to soothe babies and to comfort her charges, as well as herself and those wounded Black soldiers she encountered through her service as a medic and a spy during the Civil War.

Putting Harriet’s life and witness next to the practice of indigenous African beliefs and customs, and her direct communication through her illness with a Supreme Being and the spirit guides helped me to more fully grasp Harriet’s commitment to this life-long journey, not loosing one charge to the slave catchers or the wilderness they traversed. This made evident her internalized freedom, her mysticism, and a title taken from Barbara Holmes—a public mystic.

There were historians disputing my facts about Harriet, which caused us to get an historian friend to read through our manuscript and point out any inaccuracies. We found in this long distressing process that many of our facts were not incorrect, but needed further embellishing, as I would find references from the Smithsonian, for example, that although Harriet did not write “Wade in the Water,” which was a well known song of the enslaved, she did use it to give signal to her charges to use the waterways rather than the dense woods that may lead them to encounter slavecatchers.

There was also a meme that has become very popular as coming from Harriet: “I freed a thousand slaves. I could have freed a thousand more if they had known that they were slaves.” Those words remain true today, and as for the number of freed enslaved people being 1,000 under Harriet’s care, there was a recent PBS special on Harriet in 2022 where the number of freed people under Harriet’s care was pronounced at the end as 1,000. Given that the majority of Harriet’s work was done with stealth and clandestine, no one can be one hundred percent sure of the accuracy of numbers or dates, or Harriet’s methods in freeing her people.

This has been a personal transformation journey I have committed to make, finding the genuine in myself and owning my internalized freedom. It is the journey I wish for my whole community, and releasing it after a long journey of reading, writing, seeing, and listening with my Broadleaf editor Lil Copan, my readers, my loving husband cheering me on, the positive reinforcement from friends, supporters, historians, and the least expected, has been an act of love for which I bow in humble awe before the Cosmos, and Harriet, my spirit guide.

—

Therese Taylor-Stinson is a PC(USA)-ordained deacon and ruling elder, a spiritual director, graduate of the Shalem Institute, and a member of the Shalem Society for Contemplative Leadership. As Founding Managing Member of the Spiritual Directors of Color Network, Therese won an award for Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.

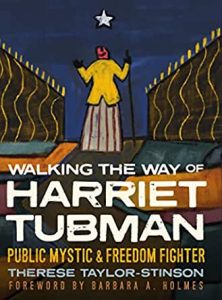

Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman; Public Mystic and Freedom Fighter

Harriet Tubman, freedom fighter and leader in the Underground Railroad, is one of the most significant figures in U.S. history. Her courage and determination in bringing enslaved people to freedom have established her as an icon of the abolitionist movement. But behind the history of the heroine called “Moses” was a woman of deep faith.

Harriet Tubman, freedom fighter and leader in the Underground Railroad, is one of the most significant figures in U.S. history. Her courage and determination in bringing enslaved people to freedom have established her as an icon of the abolitionist movement. But behind the history of the heroine called “Moses” was a woman of deep faith.

In Walking the Way of Harriet Tubman, Therese Taylor-Stinson introduces Harriet, a woman born into slavery whose unwavering faith and practices in spirituality and contemplation carried her through insufferable abuse and hardship to become a leader for her people. Her profound internal liberation came from deep roots in mysticism, Christianity, nature spirituality, and African Indigenous beliefs that empowered her own escape from enslavement–giving her the strength and purpose to lead others on the road to freedom.

Harriet’s lived spirituality illuminates a profound path forward for those of us longing for internal freedom, as well as justice and equity in our communities. As people of color, we must cultivate our full selves for our own liberation and the liberation of our communities. As the luminous significance of Harriet Tubman’s spiritual life is revealed, so too is the path to our own spiritual truth, advocacy, and racial justice as we follow in her footsteps.

BUY HERE

Category: Contemporary Women Writers