Writing a Novel with My Sister by Ambreen Hameed

Writing a Novel with My Sister

Writing a Novel with My Sister

by Ambreen Hameed

Once my sister and I decided we wanted to co-author a novel about a sibling relationship, one of the tasks allocated to me was to research how sisterhood expresses itself across the animal kingdom. The agreed plan was that I would write the older sister Sufya, and that she would be a biologist by training: someone with the habit of analysing all her relationships through a scientific lens. The kind of thing that Sufya would know, for instance, was that “the first flower to be fertilised on the Indian black plum tree produces a lethal juice which it uses to dispense with its siblings.”

My sister Uzma is a theatre-maker (as is Zarina, the younger sister in our novel Undying – one of the few points on which the story is autobiographical). Through many years of practice, Uzma is accustomed to the excitement – and the stresses and strains – of creative work that is intrinsically collaborative. My career in television production has trained me how to make space for other people’s talent, and also how to live with sometimes unwelcome editorial input.

But writing a novel is different. Many authors speak of the loneliness of writing, of the difficulty of maintaining faith, of days and weeks spent in necessary solitude, of the enormity of what must be generated by a single mind. I suspect many writers would probably also say that a novel is such an act of inward journeying, requires such unflinching inner excavation, that it cannot be written in conjunction with another human being. There is an heroic association with the quest: each of us travelling inwards must go alone, or not at all.

Uzma and I did not know at the outset what might be the perils of undertaking such a quest with another person, still less a sibling. One summer’s day in the late 1990s, we blithely began making notes for a project that would come in and out of our lives for the next two decades, and – in a sometimes unnerving expression of its own title – not leave us alone till it was finally pushed out into the world at the end the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

The practical plan for writing our novel together was the easy part. We had the beginning of a plot as soon as we decided our fictional sisters would fall for the same person, an elusive male character through whom we would explore the concept of heroism. Triangular spaces – as we knew from an old superstition told to us by our mother – were the dwelling places of djinns, and a “love triangle” we reasoned should then unleash destruction. As our plot took shape we discovered our novel would also include a fundamentalist pop group called the “Orthodogs”, a supermarket health scare involving poisoned pork, and a djinn who appears in the form of a famous Hollywood anti-hero.

Together we laid out the events of the novel with the intention that we would then each – separately – write alternate chapters. As soon as I had completed a chapter from Sufya’s point of view, I would send it to Uzma who would then write a chapter from Zarina’s point of view, taking the plot forward step by step in accordance with our agreed structure.

We had been captivated by the idea of exploring the shifting nature of truth in families – the way no two relatives, however close, can ever seem to agree on the family’s shared history and narrative. And, as soon as we started writing, this phenomenon began to manifest itself in an unexpected way: I discovered that each time Uzma sent me a chapter, I was startled by her interpretation of the “agreed” plot and characters The same happened when I sent her my chapters. This unplanned dissonance was sharply invigorating – I was delighted by the strangeness of my sister’s imagination and the appearance of elements, phrasings, insights that my own mind would never have invented. In a sense, the novel stopped being about the impossibility of congruence of sibling perspective and started – instead – to embody it.

But there were times when the dissonance was problematic. On occasion, Uzma had injected a plot device that was going to interfere with something I had in mind to do in my next chapter. With a little bit of discussion, and willingness to compromise on both sides, such issues could normally be resolved.

Much greater difficulty seemed to arise when it became clear that we – as writers – didn’t see one another’s fictional characters in the same way. Whenever this happened, communication seemed to become highly charged, and discussions turned painful. Gradually, it became clear that this was where some of our toughest work lay: in order to fully understand the sisterhood of Zarina and Sufya we would have to excavate our sibling relationship – and come face to face with some long-buried djinns of our own.

Your sibling carries a story about you that contains special truth, often right alongside unique misunderstanding. And one reason we avoid confrontation with our sisters and brothers as we get older is that – much as we wish it didn’t – it matters what they think of us. Their critique travels directly to the root of our sense of self.

Conducted over years and against the background of our changing lives – children, partners, careers – there were many difficult conversations. Some of these – had it not been for the novel – would probably never have been embarked upon, and would certainly have been left unfinished. I had to learn to live with the fact that – for my sister – my presence in her life had not always been positive. She in return learned more about me.

We discovered that the stories we had been told about each other – as so often happens in families – were not the whole truth, and were sometimes far from the truth. We learned we were not as different as we thought we were. By iteration, we learned to listen and to speak to each other in a kinder way. And above all, we slowly learned to fear our differences less.

Undying was not entered into as a therapeutic enterprise, but there’s no doubt that it had a powerful effect on our relationship as sisters. It sent us into dangerous territory and it helped us navigate out. And – another great gift perhaps of choosing to collaborate with the person who was your first playmate – writing it also made us laugh at times with the wildness of our childhood selves.

—

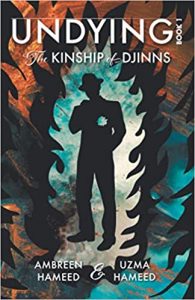

Dubbed “The Bronte sisters meet Four Lions”, Ambreen and Uzma Hameed’s two-part novel Undying is a dark comedy of sibling rivalry, Sufi spells and British Muslim identity.

About the Authors

AMBREEN HAMEED is a television producer and journalist. Ambreen’s career in television began at the BBC on the Asian programme, Network East, after which she worked for London Weekend Television, on its flagship current affairs show, The London Programme. She was series producer of the award-winning Channel 4 series Devil’s Advocate presented by Darcus Howe. Three of her London Programmes were nominated for Royal Television Society awards including an hour-long Special on the experiences of Black and Asian officers in the Metropolitan Police Service. Other career highlights include the award-winning series Second Chance for Channel 4, and Dispatches. She has also written for New Statesman and a short story for Radio 4’s Pier Shorts.

AMBREEN HAMEED is a television producer and journalist. Ambreen’s career in television began at the BBC on the Asian programme, Network East, after which she worked for London Weekend Television, on its flagship current affairs show, The London Programme. She was series producer of the award-winning Channel 4 series Devil’s Advocate presented by Darcus Howe. Three of her London Programmes were nominated for Royal Television Society awards including an hour-long Special on the experiences of Black and Asian officers in the Metropolitan Police Service. Other career highlights include the award-winning series Second Chance for Channel 4, and Dispatches. She has also written for New Statesman and a short story for Radio 4’s Pier Shorts.

UZMA HAMEED is a writer, director and dramaturg, working in theatre and dance. In 2015 she was dramaturg to choreographer Wayne McGregor on the Royal Ballet’s multi award-winning production of Woolf Works. She has since collaborated with him on Obsidian Tear (2016), Multiverse (2016) and The Dante Project – Inferno (2019) for the Royal Ballet, and on Company Wayne McGregor’s Autobiography (2017). She has also worked with choreographer Cathy Marston on Northern Ballet’s Victoria (2019), which won the Sky Arts/South Bank Show award for dance.

In 1997 she founded The Big Picture Company, a theatre company which quickly gained a reputation for its innovative visual style, combing new writing with choreography and film. For Big Picture, she wrote and directed plays which toured extensively around the UK and enjoyed London seasons at The Young Vic, BAC and Riverside Studios. From 2002-2005 Uzma was Associate Director at Derby Playhouse.

Uzma has directed for Kali Theatre, led projects at the National Theatre Studio and given talks and workshops for a variety of organisations including The Royal College of Art, Dulwich Picture Gallery, Edinburgh International Festival and Playwrights Studio Scotland.

Both Ambreen and Uzma Hameed live in the London area.

UNDYING Book 1: The Kinship of Djinns and UNDYING Book 2: My Uncle’s Son are available on Amazon in paperback (£8.99) and eBook (£2.99).

UNDYING Book 1: The Kinship of Djinns

It is 1998 and the leader of the free world is under fire after an affair with a young intern. Meanwhile, in a corner of South London, the Malik sisters have also committed a sin: they are in their thirties and still not married. Now the unexpected return of their childhood playmate spells the chance of a happy ending: but only for one of them. And this time, younger sister Zarina is determined she won’t be second in line to Sufya, the eldest – even if it means resorting to dubious occult practices. But as tensions rise across the Muslim world, sibling rivalry and Sufi spells are not the only forces with which the three lovers must contend.

It is 1998 and the leader of the free world is under fire after an affair with a young intern. Meanwhile, in a corner of South London, the Malik sisters have also committed a sin: they are in their thirties and still not married. Now the unexpected return of their childhood playmate spells the chance of a happy ending: but only for one of them. And this time, younger sister Zarina is determined she won’t be second in line to Sufya, the eldest – even if it means resorting to dubious occult practices. But as tensions rise across the Muslim world, sibling rivalry and Sufi spells are not the only forces with which the three lovers must contend.

Longlisted for The Bath Novel Award 2021

“Wildly entertaining: both an irony-sharpened comedy of manners and a powerful, passionately written dissection of anger…and tinged with magic. I loved UNDYING and couldn’t put it down until I had reached the last page.”

Stef Penney, Novelist, Winner of the Costa Book of the Year 2006

“The main characters stay with you: the entwined yet intensely rivalrous siblings, the mesmerising outsider, and a range of Muslim relatives defying all stereotypes… They take you on an audacious, at times bewildering, always enthralling journey.”

Yasmin Alibhai-Brown, Journalist, Author, Winner of the Orwell Prize

“Full of humour, passion and the kind of multi-layered portrayal of the British Muslim community that you don’t often find in fiction. It shouldn’t be possible to pull off such ambitious political scope alongside laugh-out-loud comedy.”

Viv Groskop, Writer, Comedian, Broadcaster

BUY HERE

Category: How To and Tips