Writing the Unthinkable

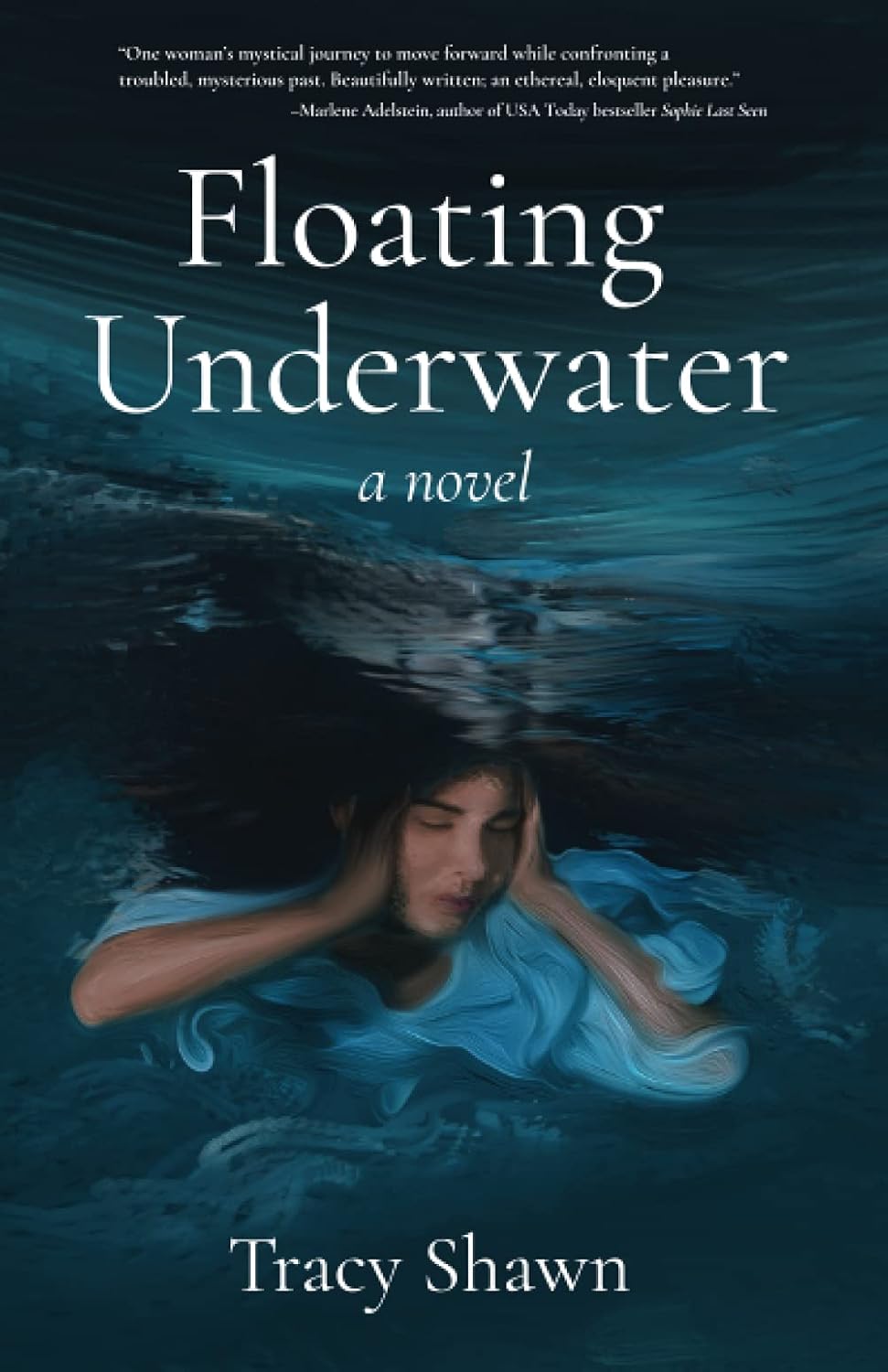

When I first started to write, it was to escape. I longed, like a snorkeler, to slip beneath cool waters and linger below the surface of another world.

When I first started to write, it was to escape. I longed, like a snorkeler, to slip beneath cool waters and linger below the surface of another world.

Bangkok was a city burning on its fringes with protests, and I began by invoking these sights and smells. This grew into a novel, a portrait of a veteran war journalist unravelling as she frantically tries to protect her secrets amid bloody, harrowing war scenes.

Five years and three drafts later, as I drifted into sleep one night, I realised that I have written a novel that I fundamentally, unequivocally, morally disagree with. A cruel female protagonist whose secrets and actions I cannot condone, and yet, it would seem now, that my entire novel sets out to justify. Actions which I have actively worked and campaigned against in my life and would do so again.

As I sat on the edge of the bed, I questioned my ability to continue. Could I abandon this novel after the often wretched progress through ill health and loss? Could I persevere in writing it so stung with disappointment and some sense of self-betrayal? Yes, with difficultly.

As women writers, I believe we absolutely should push artistic boundaries, and create women and their lives with more glinting facets and shadows. However, I question the ethics of what I have done, to take a female minority, an exception to the rule, and elevate her and her acts for fiction. There is discomfort in this blurring of lines where writers, creativity, ethics, and responsibilities to readers – to other women – meet.

In a BBC Hardtalk interview in 2012, Lionel Shriver said that she wanted her writing to “shine a light into the dark corners” of people’s lives. This was a catalyst for me. I felt strongly as a woman and as a feminist that in my work I would want to challenge and provoke, to subvert the female norm as much as I could bear.

I am not alone. Literary and commercial fiction ply us with female protagonists to despise and pity. Women writers sate us with bad girls who are riddled with shame and a desire for repentance (The Girls), who are sadists (The Piano Teacher), psychotic avengers (Gone Girl), or flawed, obsessive observers (The Girl on the Train). We excel in putting our protagonists on the rack and cranking the wheels without voyeurism (The Vegetarian, The Little Life). We create stories that can be graphic and disturbing, and that pull readers gasping into the page.

As a reader, we may skip the pages when it is a step too far. But how do we actually write the unthinkable or unethical? Is there a line that we start to cross, hover above, and then retreat from? In March this year, Hanya Yanagihara described to The Telegraph that in writing A Little Life, she “wanted it to capture all the love, distress and horror of life… it could be a very dark world to occupy.” A friend described to me how she would handwrite her unthinkables onto paper and then, at the end of the day, she would set heavy books on top. This contains the grotesques, she said, they were unable to crawl out. She directed her characters with compassion, torturing and then cosseting them, before locking them safely away, out of sight.

In a previous draft of my novel, I planned to explore an all too frequent consequence of conflicts and male power – rape used as a weapon of war and oppression. One character, then two, would endure this, as would the reader. As a writer, I couldn’t cross this line – I couldn’t depict this atrocity nor inflict this suffering on my characters. I also couldn’t risk trivialising such a violation. This was the right choice.

Then, as my novel and my protagonist became fully formed, her secrets began to emerge. I realised what it was she had done, what she had hidden. I agonised with this: I couldn’t bear to fictionalise rape, could I commit to telling this? For six months I was unable to write, unable to see how to approach it. I refused to show it or tell it, but doubted it was sufficient to only imply or suggest. I rejected this premise and searched for another route; I must censor myself. But in the end I didn’t. Her hidden secret turns the key in the lock of the plot and is the right development for her character.

This decision comes at a cost to me. I see these scenes approach again, and I must confront and tether them. I must embolden them to tell a story almost unbearable to read. I want to stretch near to breaking point my reader’s compassion, for her, for her acts. To do this as a writer I will plunge into the underwater gloom, deeper this time, and hold my breath.

As a first time novelist, I have not yet learned the detachment in this process. As Anya Mathis wrote in the New York Times in September: “a debut novel is piece of the writer’s soul.” This is the piece of mine. It is wrenched from me.

We write, and we must live with the tale that we unwind, and the unthinkables that we unleash. We luxuriate in the privilege of doing so. After all, I will remind myself, it is not real life, it is only another, darker world.

—

References:

BBC Hardtalk interview: Lionel Shriver

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5dMMBuWEn0

The Telegraph: Hanya Yanagihara

New York Times: Anya Mathis

—

J L Hall is a Scottish novelist living in London, where she is currently editing her debut novel, The Paper Crane. In 2016, she was longlisted for the Lucy Cavendish College Fiction Prize, and shortlisted for the Impress New Writers Prize.

When she is not editing, J L Hall works as a lecturer and non-profit consultant in the creative industries. She lives in North London with her partner where she attempts balcony gardening, and travels to near and far flung shores whenever she can.

To find out more about J L Hall, please visit her website www.jlhallwriter.com or follow her on Twitter @jlhallwriter

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing

I once wrote a story about a war criminal. It’s hard, it’s uncomfortable, but it is impossible to avoid telling the stories, and the characters, that haunt us.

Well done!

Thank you so much for sharing this. I’m of the view that it’s absolutely critical for women to write ugly women – damaged women, angry women, flawed women, real women. I’m so tired and demoralised by women who are unquestionably forgivable. Women who are damaged only by their fertility, or lack thereof. Women who are healed by men. Women who are mere vessels for a weight of societal expectations. Thank you for writing a woman as unethical, unlikeable – it’s not fair that men get to solely rule that domain. I’ll be keeping an eye out for your work – I look forward to seeing more pieces of your soul 😉

Thanks for an interesting and thought provoking article. I recently abandoned a book because I couldn’t bear to write the things the character (male) ended up doing and, as you say, I worried about trivialising, or even showing sympathy for, something horrible. Writing something from the point of view of the victim is easier to countenance than writing it from the point of view of the aggressor.

This is the first time I’ve abandoned a book (albeit something different to my usual genre), which is scary in itself because if I can abandon one…