Insults, Ordinary objects, and Empathy: A Doctor Discusses Empathy Through Writing

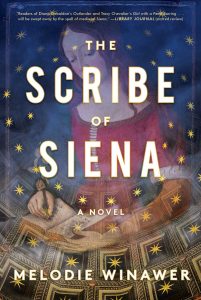

My first meeting with Neslihan Senoçak, an expert on medieval Italy, didn’t start well. I was in the early stages of writing my first novel, The Scribe of Siena, and I’d managed to get Nesli to meet with me. But she looked suspicious. After several minutes of introductory niceties, I realized why.

My first meeting with Neslihan Senoçak, an expert on medieval Italy, didn’t start well. I was in the early stages of writing my first novel, The Scribe of Siena, and I’d managed to get Nesli to meet with me. But she looked suspicious. After several minutes of introductory niceties, I realized why.

She expected the worst—that I was planning to write a novel about illiterate people who revel in torture and stab their food with a knife; that I would resort to negative stereotypes of a culture she had devoted her career to studying.

The word medieval is often used as an insult, a synonym for backward, crude, and unevolved. It is used to describe people who are not only unlike, but patently inferior to our modern, sophisticated selves. But that wasn’t what I’d intended, and when Nesli realized that my protagonist Beatrice, a 21st century neurosurgeon, would be so moved by the sweetness and beauty of medieval life that she would question the wisdom of her modern existence, she warmed up quickly.

I spent the next two hours, (and then the next four years), learning about a complex, elegant legal system, literacy in 14th century Italian women, and one remarkable city’s devotion to the creation and protection of spectacular art. I learned about, cooked, and tasted a seven-hundred-year-old cuisine flavored with fresh almond milk, nutmeg, black pepper, and pomegranate. And I learned about a mystery—the unanswered question of why Siena fared so badly during the Plague, and failed to recover afterwards, eventually conquered by its long-time arch rival Florence.

Differences between medieval and modern life can make the past seem strange and unappealing. Some are colossal—lack of formal education for women, or the absence of electricity and computer technology. Some are minor inconveniences, like missing toilet paper and zippers. But not everything was different then. Medieval people loved a hot bath just as much as 21st century people do. It was just harder to get one without hot running water. And they called themselves Nos Moderni—“we modern people.” They thought they were modern too.

Finding similarities can mitigate that sense of strangeness. Six hundred and fifty years ago, people longed for but also feared childbirth. Children learned their letters, teenagers bumbled through their first stirrings of love, people trained for new jobs, put money in banks, and gossiped on street corners. They grew, aged, and reached the ends of their lives with satisfaction and sometimes regret. They, like us, mourned those who were gone. Recognizing what we share with the past can take us out of ourselves and into the minds and hearts of people who lived hundreds of years ago. It’s a loaded word these days, but I’ll call it empathy.

The power of shared experience fuels historical fiction. But that synergy isn’t limited to fiction set in the past. We have enough differences from one another in our own time, in our own country, even within our communities, to keep us busy forever.

The power of shared experience fuels historical fiction. But that synergy isn’t limited to fiction set in the past. We have enough differences from one another in our own time, in our own country, even within our communities, to keep us busy forever.

Empathy, the recognition of the uncannily familiar in someone other than yourself, can help bridge the gaps, mitigate suspicion, anger, and the tendency to violence. The fundamental human struggle and longing to be understood and to understand, the bliss of burdens lifted, of desires fulfilled, of fears allayed transcends temporal and spatial boundaries. That synergy, empathy, search for connection, propels us to write, and to read.

I write historical fiction so that I can bring the past to life—to recreate a time and place in such a vivid and believable way that the story becomes a vehicle for virtual time travel. A good story can introduce you to people whom you don’t just laugh at or despise for their strangeness, but whom you might admire, connect with, and even love, even though the last of them died more than 600 years ago.

People have asked how I choose facts to include in my historical writing, how I decide where research ends and fiction begins. When the place feels real enough to walk through, and the people act of their own accord, I’ve done it right. Often something small and concrete is enough to make the past feel close enough to touch. A wooden top a child played with hundreds of years ago, an amulet of protection worn down by worrying hands, hooks and eyes from a Byzantine dress that look exactly as they do today. Maybe, you might think, maybe those people weren’t so different after all.

In addition to being a writer, I’m a doctor—a neurologist. This puts me in the privileged but often sad position of helping patients who are losing the ability to move, see, think, speak, remember, and love. Empathy allows me to understand the choices they make about their lives, and to help them navigate the labyrinth of their illnesses.

I care deeply for my patients, but every day my work tests the boundaries between myself and those whose suffering I experience. I may diagnose a patient with the same condition that killed my father, or care for a person whose symptoms mirror those I have feared in myself, or my children. But despite all that, I need to keep enough distance to do my job well, and not lose myself in the process.

My experience of a physician’s empathy—its power for good, but also its dangers– led me to write The Scribe of Siena, and to create my protagonist Beatrice. How far could empathy take her—could it extend to the written word, even words written hundreds of years ago? Could it blur the boundaries not only between self and other, but between times?

For Beatrice, who touches patients’ brains with her hands, empathy and its consequences unravel her orderly life. I set the book in Siena because it is simultaneously modern and medieval, a city where the past and present coexist. It is the perfect place for this story of a woman who, at first against her will, and then by desire, loses her place in time.

Why write or read about history? Why care about people who no longer exist, who come from a time so different from ours? Maybe looking back and understanding what we see—not just academically, but personally—will help shrink differences we find closer to home. At its best, fiction has the power to foster connections not only across the centuries, but also across the modern walls that divide us.

—

Melodie Winawer is a physician-scientist and Associate Professor of Neurology at Columbia University. A graduate of Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, and Columbia University with degrees in biological psychology, medicine, and epidemiology, she has published over fifty nonfiction articles and book chapters. She is fluent in Spanish and French, literate in Latin, and has a passable knowledge of Italian. Dr. Winawer lives with her spouse and their three young children in Brooklyn, New York. The Scribe of Siena is her first novel.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/authorMelodieWinawer/

Twitter: @melodiewinawer

Website: http://melodiewinawer.com/

About The Scribe Of Siena

Equal parts transporting love story and gripping historical conspiracy, debut author Melodie Winawer takes readers deep into medieval Italy, where the past and present blur and a twenty-first century woman will discover a plot to destroy Siena.

Accomplished neurosurgeon Beatrice Trovato knows that her deep empathy for her patients is starting to impede her work. So when her beloved brother passes away, she welcomes the unexpected trip to the Tuscan city of Siena to resolve his estate, even as she wrestles with grief. But as she delves deeper into her brother’s affairs, she discovers intrigue she never imagined—a 700-year-old conspiracy to decimate the city.

After uncovering the journal and paintings of Gabriele Accorsi, the fourteenth-century artist at the heart of the plot, Beatrice finds a startling image of her own face and is suddenly transported to the year 1347. She awakens in a Siena unfamiliar to her, one that will soon be hit by the Plague.

Yet when Beatrice meets Accorsi, something unexpected happens: she falls in love—not only with Gabriele, but also with the beauty and cadence of medieval life. As the Plague and the ruthless hands behind its trajectory threaten not only her survival but also Siena’s very existence, Beatrice must decide in which century she belongs.

The Scribe of Siena is the captivating story of a brilliant woman’s passionate affair with a time and a place that captures her in an impossibly romantic and dangerous trap—testing the strength of fate and the bonds of love.

Category: Contemporary Women Writers, On Writing