When Facts Become Fiction: From Journalist in Rwanda to Novelist

Novels usually draw, to some degree, on personal experiences and historical research, and memoirs have come a long way since the scandal of James Frey’s personal revelations being more fiction than fact. The blurring of lines between the real world and the imagined has been an interesting process for me during the eleven years I spent writing In the Shadow of 10,000 Hills (April 2018, Central Avenue Publishing).

Novels usually draw, to some degree, on personal experiences and historical research, and memoirs have come a long way since the scandal of James Frey’s personal revelations being more fiction than fact. The blurring of lines between the real world and the imagined has been an interesting process for me during the eleven years I spent writing In the Shadow of 10,000 Hills (April 2018, Central Avenue Publishing).

Yes, it’s a novel, but the seeds of the story were planted during a month-long trip I took to Rwanda as a journalist, and then sown during years of research. The souls of the characters are based on people I met there. I could never have written this story without experiencing the sorrow and hope, grief intertwined with love like strands of DNA, in this country first-hand.

I went to Rwanda in 2006, twelve years after the devastating genocide that wiped out more than 1 million Tutsis, to interview survivors about the connection between grief and forgiveness. I spent two weeks in the capital city of Kigali, mostly reporting on humanitarian nonprofits helping genocide survivors to tell their stories in a safe space.

Toward the end of my first week in Kigali, I was invited to a small group meeting of genocide survivors, all women in their mid-thirties to mid-forties. The minister of the Solace Ministry, which conducted the group, told me that it was taboo to speak of the genocide atrocities in public. Women in particular were shamed into silence. But that night, I witnessed perhaps a dozen women stand up in the dark sanctuary, one by one, and tell bits and pieces of a shared legacy of horror:

My mother and father, two older sisters and brother, were hacked with machete while I watched from a crawl space in ceiling. I was the only one small enough to be tucked up there.

The soldiers came to our school. They took all of the Tutsi children into the gymnasium. When the shooting began, I lay flat on the floor, eyes shut, and prayed they would believe I was already dead.

I held a hand over little brother’s mouth so he can’t scream.

I made my mind blank and my body steel so that I could not feel the weight of the soldier on top of me, inside of me.

There were few tears shed as people told their stories; the silence was so thick it felts as if the room itself was breathing. I was overwhelmed by the feeling of oneness in that room, the power of shared stories to bring people closer together.

After the group meeting, I interviewed a young woman named Nadine, each of us sitting at opposite ends of a couch. She had returned to Rwanda, after years of living in Kenya, to testify at the trial of a man who was high up in the Hutu army. He had killed her mother and her sister. I shared with her that I had also lost a sister, Susie when I was a child.

Nadine leaned in to hug me. “I am so sorry, inshuti,” she said. Friend. She patted my back, clucked her tongue as if soothing a child for what seemed like a long while. There was nothing I could do but accept her consolation. It seemed easier for her to give comfort than receive it. And yet I longed to break free, to inch away from her to the far side of the couch. It was uncomfortable, this girl who had lost so much, comforting me. And yet, it put my own grief into perspective. I experienced the power of shared stories in a very personal way.

A funny thing happened during the first two weeks I was in Rwanda: all three of the magazine’s assignments I had secured before leaving fell apart. I went into the foothills to find more stories I could report on as a journalist, and during that journey, I became a novelist.

I experienced powerful connections with strangers who lived halfway around the world from me, in a culture so different than mine, through both love and grief. I wanted to share those experience — what I felt — with others. It didn’t hit me until I returned home to Seattle that the best way to do that was through developing characters that encompassed many facets of the people I met, as well as answer the questions I still had about the role that forgiveness plays in resolving grief.

For example, Nadine, the woman I met at the Solace Ministry, started out with a small role in my novel. It wasn’t until seven years into revisions that I cracked open the story this real person told me, took the facts of her life and spun them out into a plot line — and a character — that was of my own imagining. Nadine is now one of three primary characters in this story about three women searching for family and peace in post-genocide Rwanda.

During the next eleven years, I would continue to create my novel world, through the experiences I had in Rwanda, the many historical and spiritual books I read, and my imagination. I grew as a person as well as a writer. I became not just a journalist, but also a novelist.

Jennifer Haupt’s essays and articles have been published in O, The Oprah Magazine, The Rumpus, Psychology Today, Travel & Leisure, The Seattle Times, Spirituality & Health, The Sun and many other publications. In the Shadow of Ten Thousand Hills (April 2, 2018, Central Avenue Publishing) is her debut novel.

Website: www.jenniferhaupt.com

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jenniferhauptauthor/

Twitter: @Jennifer_Haupt

Instagram: @jenniferhauptauthor

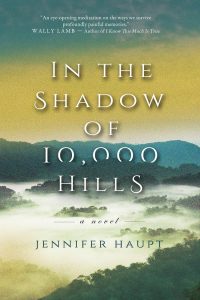

About In the Shadow of 10,000 Hills:

“Both an evocative page-turner and an eye-opening meditation on the ways we survive profoundly painful memories and negotiate the complexities of love. I was deeply moved by this story.” — Wally Lamb, NY Times bestselling author of I Know This Much is True

“Both an evocative page-turner and an eye-opening meditation on the ways we survive profoundly painful memories and negotiate the complexities of love. I was deeply moved by this story.” — Wally Lamb, NY Times bestselling author of I Know This Much is True

“This blazingly original novel is about the illusions of love, the way memory can confound or release you, and the knotted threads that make up family — and forgiveness.” — Caroline Leavitt, NY Times bestselling author of Pictures of You

IN THE SHADOW OF 10,000 HILLS is a sweeping family saga that spans from the turmoil of Atlanta during the Civil Rights Movement through the struggle for reconciliation and forgiveness in post-genocide Rwanda. At the heart of this literary novel that crosses racial and cultural boundaries is the search for family on a personal and global level.

In 1967, a disillusioned and heartbroken Lillian Carlson left Atlanta after the assassination of Martin Luther King. She found meaning in the hearts of orphaned African children and cobbled together her own small orphanage in the Rift Valley alongside the lush forests of Rwanda.

Three decades later, in New York City, Rachel Shepherd, lost and heartbroken herself, embarks on a journey to find the father who abandoned her as a young child, determined to solve the enigma of Henry Shepherd, a now-famous photographer.

When an online search turns up a clue to his whereabouts, Rachel travels to Rwanda to connect with an unsuspecting and uncooperative Lillian. While Rachel tries to unravel the mystery of her father’s disappearance, she finds unexpected allies in an ex-pat doctor running from his past and a young Tutsi woman who lived through a profound experience alongside her father.

Set amongst the wounds of a country still healing today, follow the intertwining stories of three women who discover something unexpected: grace when there can be no forgiveness.

Category: How To and Tips, On Writing