Why Diversity Is Important – Atypical Plays For Atypical Actors

“You have to see it, to be it.” This slogan seems to be cropping up everywhere in these diversity-conscious days, whether it’s about creating role models or better representation for girls, mature women, or what is increasingly known as BAME – individuals from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic origins. It is particularly important in the media, which supposedly mirrors our society and whose powerful imagery helps shape our values, morals, norms, and ambitions.

“You have to see it, to be it.” This slogan seems to be cropping up everywhere in these diversity-conscious days, whether it’s about creating role models or better representation for girls, mature women, or what is increasingly known as BAME – individuals from Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic origins. It is particularly important in the media, which supposedly mirrors our society and whose powerful imagery helps shape our values, morals, norms, and ambitions.

Moving image media, theatre, and novels help us understand the world, our feelings, relationships, and social responsibilities, playing a crucial role in communicating what is ‘appropriate’ for our age, gender and cultural heritage.

Female protagonists? No… For far too long women were harridans or eye candy, the supporting cast hanging onto the white male hero’s arm, or being dismissed as a nag and a hag. Black and Asian actor friends despaired at being cast, yet again, as the gangster/drug dealer, the ‘exotic’ princess, or victim daughter forced into an arranged marriage.

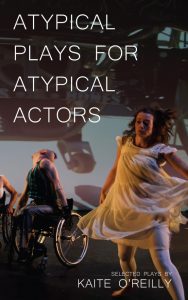

These limited and limiting stereotypes proliferate in books, on screen, and stage, and although the situation is slowly improving, these harmful ‘types’ and narratives still linger, constantly reflecting negative images of ‘difference’. Never is this more obvious, I would argue, than in the representation of impairment – part of the diversity argument we still hear little about. The desire to subvert or challenge harmful images of disability is what fired my writing Atypical Plays for Atypical Actors, published by Oberon.

Tiny Tim. Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dam. Mrs Rochester, the mad woman in the attic. Captain Hook. Richard III….to name just a few. Since Oedipus, disability has been used in the western theatrical and literary traditions as a useful shortcut to signify evil, helplessness, instability, and a plethora of other negative human traits that inspire pity or fear. The images continue in films: the tormented genius, the evil Bond ‘baddie’, the blade-slashing psychopath, the victim who conveniently leaves the scene either by dying, being institutionalised, or ‘overcoming’ the condition and so ‘passing’ as non-disabled…

There are few, if any, positive representations in books and media of characters with physical and/or sensory difference, or who are neuro-atypical. This is partly because until recently there were few writing books and screen/plays who identified as Deaf or disabled, or who wrote informed by that lived experience.

Disability is a ‘useful’ vehicle to explore our fears of difference, a ‘helpful’ yardstick against which we can measure ourselves in a binary of being ‘normal’ or not. It isn’t by accident disabled characters are often the exiled monster, the interloper whom the village unite against and cast out. Imagine then the impact such negative, outsider roles have on the consumers – those who are disabled, and those who are not….

I have a long history and relationship with what is known in the UK as disability arts and culture. I joined Graeae, the leading theatre company for practitioners with physical and sensory impairments, as a young performer several decades ago. I shifted from the stage to behind a computer, wanting to tell different stories, with different protagonists, to be performed by talented actors who happened to have an impairment, rather than non-disabled actors ‘cripping up’.

Atypical Plays for Atypical Actors is the result of over a decade’s work, all commissioned and professionally produced scripts, some award-winning, all responding in someway to the culture, politics, and times around me.

The Almond and the Seahorse is a character-led play about the survivors of Traumatic Brain Injury, TBI. It was initiated by my frustration at a spate of television and stage productions in the early noughties featuring TBI as a horrifying event, decimating families. Of course such an injury is devastating, and I would never for a moment undermine the impact such changes have on individuals and families. But each case is unique, and I found the lingering dramatisation of despair prurient. The dramas were depressing and unremittingly negative – very different from the actual lived experience of TBI that friends and members of my family have had.

The Almond and the Seahorse, named after the amygdala and hippocampus–parts of the brain’s circuitry–sought to ‘answer back’ to chilling representations that gave no hope. My own piece is hard-hitting, yet at its premiere in Cardiff in 2008, members and users of Headway, the TBI charity, cried and congratulated me for ‘showing my story’ – whether as TBI survivor or family member.

It was cathartic and important for them to see a version of ‘themselves’ dealing with change as a normal part of life, without ‘magical thinking’, happy ever afters, or (the more usual) horror endings. The play has since been produced widely, from Estonia to Germany and several readings in the USA, suggesting a growing interest in stories that reflect common experience without sensationalising the medical angle.

It was cathartic and important for them to see a version of ‘themselves’ dealing with change as a normal part of life, without ‘magical thinking’, happy ever afters, or (the more usual) horror endings. The play has since been produced widely, from Estonia to Germany and several readings in the USA, suggesting a growing interest in stories that reflect common experience without sensationalising the medical angle.

Another character-led play in the selection is Cosy, a family drama for six female performers, playing ages 16 to 76. As a performer I was frustrated by the dearth of female parts after a certain age, and so this script counters that, putting the ‘invisible ages’, from forty plus, centre-stage, in an exploration of aging, sibling dynamics, and how we shuffle off this mortal coil.

The three remaining texts in the book are more experimental in form and aesthetic, proving how innovation arrives when writing for ‘atypical’ actors. The 9 Fridas is structured like a mosaic, with multiple versions of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, reclaiming her as a disability icon and not a broken, betrayed little wife, as seen in some recent depictions.

In Water I’m Weightless is a montage of disability and Deaf experience, produced by National Theatre Wales and Southbank Centre as part of the Cultural Olympiad, the official festival celebrating the 2012 London Olympics and Paralympics. Finally, peeling revisits the pity of war through the eyes of a gossiping, soup-making, contemporary chorus in a metatheatrical production of ‘The Trojan Women: then and now.’

What I have tried to do with these plays is to subvert the tropes and challenge the narrow gauge of ‘normalcy’, celebrating all the possibilities of human variety. I have made sassy, active, sexual female characters from a wide variety of age and cultural backgrounds, the protagonists of their own lives. There is pain and joy, grief and disappointment in their encounters with others, there is success and failure, just as for other lead characters in thousands of books and plays. The difference is ‘difference’ made visible and taken for granted, just as a ‘normal’ part of ‘normal’ life for ‘normal’ characters. Let’s broaden our definitions and get rid of binaries.

‘You have to see it, to be it.’

© Kaite O’Reilly 2017.

—

Kaite O’Reilly has won many awards for her work, including the Peggy Ramsay Award, M.E.N. best play of the year, Theatre-Wales Award and the Ted Hughes Award for new works in Poetry for her reworking of Aeschylus’s ‘Persians’ for National Theatre Wales in their inaugural year. Her plays have been translated/produced in eleven countries worldwide.

A leading figure in disability arts and culture in the UK, she received two Cultural Olympiad Commissions for ‘In Water I’m Weightless,’ produced by National Theatre Wales/Southbank Centre as part of the official festival celebrating the 2012 London Olympics/Paralympics.

She has recently been awarded an International Unlimited Commission to develop The Singapore ‘d’ Monologues 2017/18. A fellow of international research centre ‘Interweaving Performance Cultures’ at Freie Universitat in Berlin, she is reflecting on her practice between hearing culture and Deaf culture, disability culture and ‘mainstream’ culture. Her plays are published by Faber & Faber, Aurora Metro and Oberon – most recently the critically acclaimed Atypical Plays for Atypical Actors.

www.kaiteoreilly.wordpress.com

Category: On Writing

Comments (1)

Trackback URL | Comments RSS Feed

Sites That Link to this Post